High in the mountains of south-western China, can this be the real thing?

As my plane descends through cloud in the northern corner of China’s Yunnan province, I see as good an omen for a journey as I’ve ever seen: the plane’s shadow is surrounded by a ring of rainbow colours. Buddha’s Aureole, the Chinese call this phenomenon, caused by water droplets in the cloud refracting light.

We drop through the white canopy, passing over farmhouses and fields as the plane lines up for landing. Walking to the arrivals hall, I see the lettering on the airport building: Shangri-La.

Shangri-La? you ask. Can it be that mythical place? That’s what I’m here to discover.

It seems that, in 1995, Tibetan scholar Xuan Ke deduced that Shangri-La — the utopia described by British author James Hilton in his 1933 book Lost Horizon — was based on the Deqing Prefecture. Xuan held that the author learned about the area from Austrian-born explorer and botanist Joseph Rock, who led pioneering expeditions in Yunnan during the 1920s and 1930s. Not slow to see the potential in this, Zhongdian, the main town in the area, changed its name to Shangri-La in 2001.

After I collect my bags and reach the airport exit gate, travel agents Shen Xiaozhu and his athletic-looking wife A Xiang La Mu, introduce themselves: “We’ll be your guides today,” says A.

Zhongdian lies at around 3,280 metres above sea level, and on this October morning the thin air is chill as Shen drives us along a near-deserted highway.

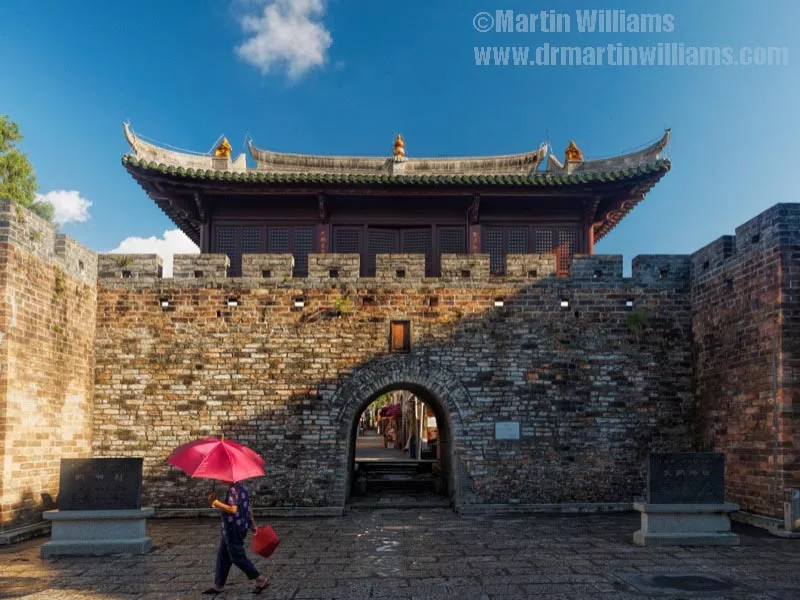

My first glimpse of the town has promising hints of nirvana: broad thoroughfares lined with three-storey buildings, many gaily painted in reds and oranges. It seems appropriately relaxed, with neither pedestrians nor vehicles in any hurry; a yak plods past, pulling a cart. We park, enter a tiny restaurant for breakfast, and huddle round a metal basin filled with glowing coals as breakfast arrives on a knee-high table.

I enjoy slices of fried potato and scrambled egg with tomato, eaten with chunks of unleavened bread. “Some foods and drinks were more pleasant than others” in Hilton’s Shangri-La and it’s true of this place too. I find a cup of yak-butter tea hard going, like salty sour cream with flour.

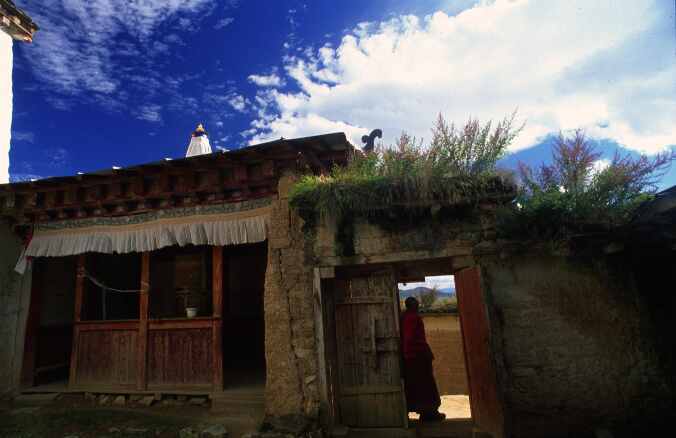

We head for Gedansongzanlin Lamasery. Imposingly set on a low hill, this ancient place is a good match for Shangri-La’s lamasery. The main hall has golden statues and walls adorned with paintings of Buddha and fanciful beasts. Hilton described similar artworks, but I see no sign of the comforts of home he mentioned – porcelain baths from Ohio or central heating.

Nirvana-dwellers are hardy, it seems. There is no heating in my hotel room, and I sleep fully clothed under two duvets.

White Water Terrace

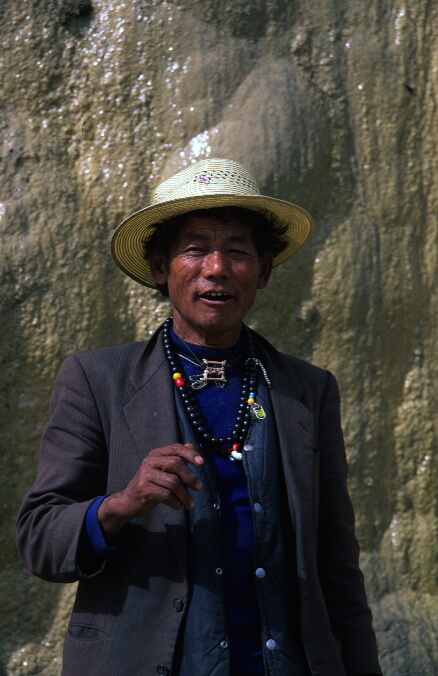

Next day I head south for White Water Terrace, 103 kilometres from Zhongdian. Here streams from limestone hills have deposited tufa (calcium carbonate) in a series of terraces like frozen, creamy cascades. I meet a Dongba-priest, He Zhichang. He wears a brown jacket, necklaces of black beads and a jaunty straw boater, contrasting with his sun-darkened, wrinkled face.

“Come and have a look,” he instructs in accented Mandarin, leading us to a terrace a few metres away. Pointing at a fist-sized hole in the tufa, he says, “A god lives here,” explaining that in the local Dongba belief, spirits reside in all things, and must be prayed to in order to avoid calamities.

Reaching into a pouch, He Zhichang hands me a pile of rice grains, and instructs me to throw it, motioning towards the hole. I make my offering, and again follow instructions by gently knocking my head on the cascade. “You’ll be lucky and healthy,” he assures me.

Sixty-nine-year-old He Zhichang comes here every day, and practices writing Dongba pictographs in a tatty exercise book, which he’s been doing for ten years. The Dongba written language which the Naxi people use is the world’s only living pictorial language, although it only just survives. Glancing at his latest page, it seems to me that the writing’s like Egyptian hieroglyphics hybridised with Chinese. “It was difficult to study them before,” He Zhichang says. China’s Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 included attempts to sweep away the Naxi culture, and a few years elapsed before open study became acceptable again.

Back in Shangri-La, Shen and A suggest an evening of Tibetan music and dance. Such traditions are now permitted – even encouraged.

The performance is held in a large family house. We climb a flight of stairs to a room with benches and low tables arrayed around a central pillar. We sit nibbling snacks including bread and nuts washed down with cups of grain liquor with a kick like schnapps.

A woman in a blue traditional dress starts the show with a slow, haunting aria. Other numbers are more boisterous. Encouraged by Shen, I join a dance, linking arms with men who chant a chorus, swinging their feet and stomping as they lead the rest of us round the pillar. They accelerate with each chorus till we’re swinging and stomping at running speed. I peel off to catch my breath.

Later as I snuggle down under my duvets I find myself thinking: tonight was a lot more fun than any of the austere evenings of the fictional Shangri-La.

Autumn in Shangri-La Gorge

Shangri-La Gorge

Next day I head for Shangri-La Gorge, named for similarities to a valley Hilton described. I am met by bespectacled Zhao Weidong, project assistant with the Nature Conservancy, a US-based organisation dedicated to saving the earth’s “last great places”.

The gorge is narrow, with towering cliffs and shrubs incandescent yellow against the dark backdrop. Zhao stops to photograph a tree festooned with red berries. “Food for bears,” he says. Black bears and wolves are now scarce in much of China but, according to locals, thrive in the valley.

Three days’ walk down the gorge leads to warmer places, says Zhao, who’s involved in field surveys yielding an impressive diversity of plants and animals. Many are unique to southwest China, including rhododendrons, treasured by gardeners everywhere.

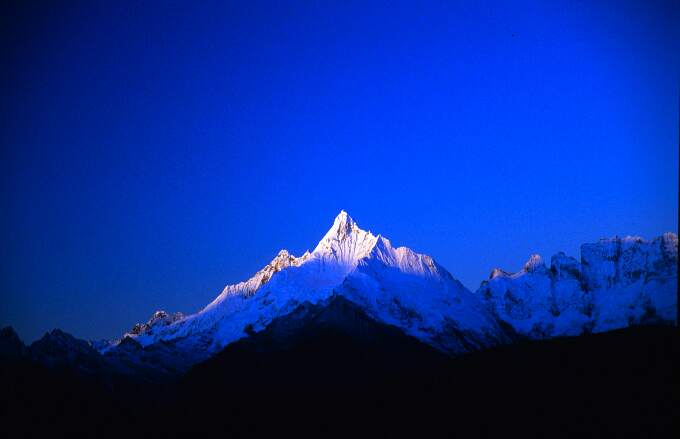

By now I’ve seen many hints of Hilton’s Shangri-La, but I’m still missing a key item: a clone for Karakal, a snow peak which in Hilton’s book appeared to be “an almost perfect cone of snow.”

Deqin and Meili Snow Mountain

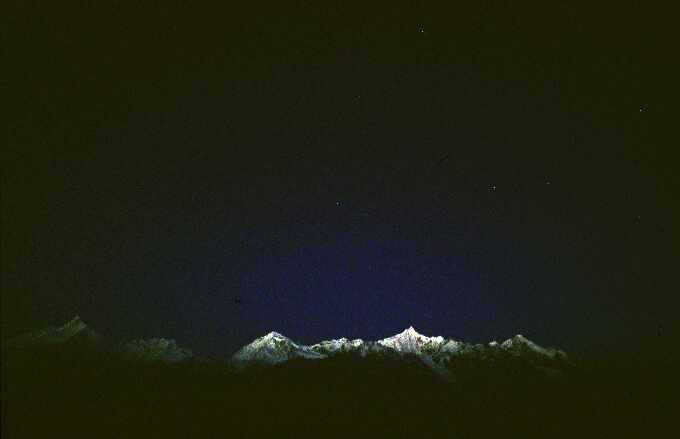

I have read that there is a mountain to the northwest that could be a good match: Meili Snow Mountain. With driver Yu Yong-sheng, I set off over the upper Yangtze River. We find a hotel, then, in the last hour of daylight, drive to a vantage for the snow mountain, but it is shrouded in mist.

Next morning we set off before dawn. Soon, a band of snow peaks appears, milky pale in the darkness. Near the middle is the highest, 6,740-metre Kawagebo. Another, Miancimu, stands aloof to the left. Both are close to being perfect cones, from which glaciers snake down through the snow line.

Suddenly the tip of Kawagebo catches fire with the first rays of the sun. A tide of orange floods down the peak and its neighbours. The orange turns paler, becomes white, and the forests across the ravine appear green. I’m ecstatic; this is a dawn worthy of any Shangri-La and worth the trip on its own.

Zhongdian: cranes at Napahai wetland

Back in Zhongdian, a drizzly day deters me from heading into the hills, and gives me a chance to renew a lifelong passion of bird-watching. Guidebooks report that a wetland, Napahai, beside the town is the winter home to the rare black-necked crane. Standing 1.5-metres tall, the birds are regarded by Tibetans as spirits, symbols of luck and happiness. They’re globally threatened, with maybe only 6,000 in total.

“The cranes won’t arrive till later this month,” a local warns. But on this grey day I decide to try my luck anyway. In the wetland I spy thousands of ducks, but no cranes. Then, as I scrutinize distant fields through my telescope, I see movement. A group of eight cranes move with graceful strides, searching for plant roots and small prey. They’re mostly silvery-white, with red caps topping black necks and shaggy black tips to their wings. As I watch, four more of the birds fly in on broad wings, a perfect picture against the yellow-tinged woods behind.

Dr Ho in Lijang: being happy is the best medicine

One aspect of Hilton’s Shangri-La has so far eluded me: the key to longevity. His Shangri-La was presided over by a mysterious former missionary, who through drug-taking and deep-breathing exercises had lived to well over 200. Might I discover a similar recipe?

In a hamlet just south of Zhongdian county, I see a sign that immodestly announces the surgery of “The Famous Dr Ho.” I enter a single-storey wooden building and meet a man clad in a woolly cap, with the grey whiskers and wispy beard of an archetypal Chinese sage. It is Dr Ho Shay-hsou.

“Come in please, welcome!” says Dr Ho who is famous at least partly because he loves telling visitors – in excellent English if they don’t speak Chinese – about his life. He has devoted it to exploring the healing properties of plants growing on nearby Jade Dragon Mountain. Ho asks me, “What can I do for you?”

Ho is 80 now, but still treating patients. “I’ve had success treating leukaemia with traditional Chinese medicine,” he adds, showing me a sheaf of letters. “Now I’m writing a book.” I’m interested, but seek something different.

“Can you make me a potion to help me live to over 200?” I ask.

Ho reckons it might be possible to live that long in future, but not now. And he doesn’t recommend potions as the chief means of extending life. “Being happy is the best medicine,” he says. “Medicine is external. Internal is more important.” It’s hard to argue with that and a good note on which to end my quest.

So, is this Hilton’s nirvana? Eric Lee, a visitor from California puts it this way: “Shangri-La is in your mind”. He says: “It’s all the great places you’ve ever been.”

Maybe so. But if nothing else, “Shangri-la” certainly deserves its name. For I found magic, majesty… even happiness there.

This article first appeared in the Chinese edition of Reader’s Digest. Reader’s Digest holds copyright in the text.

Shangri-La article in Chinese (pdf)

Shangrila

What a great article and photos. I am back home in Australia after visiting Tibet and northern India recently. I am now planning soon to travel up the Mekong thru Laos and up to Shangri-La. Is it possible to get there on one’s own?

Janet

Shangri-la independently

Hi Janet:

Well, if you can make it up from Laos, should be easy to reach Shangri-la!

Quite possible independently: I did trip by muself, just with some help from small local travel agent (which I only contacted via another agent): no translator, tho I speak some Mandarin.

Easier now, maybe, as Zhongdian aka Shangri-la more on the tourist trail.

Martin