Skidding through dark mud, I clutch a bamboo stem to pull myself up the faint trail, brushing through knee-high grass that’s still wet from overnight rain. Ahead of me, one of my traveling companions, Perfecto Balicao, is making fluid, easy progress, pausing only to use his machete to cut the thin branches overhanging the path. Below us lie steep fields of maize stubble, rolling farmland and grassy hillsides.

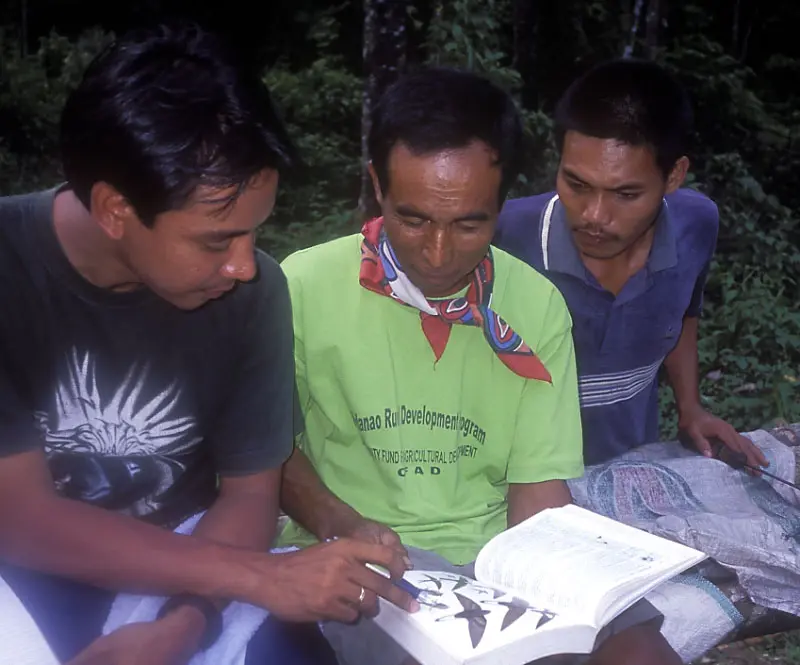

We’re climbing a spur of Mount Sinaka, a squat hill on Mindanao in the southern Philippines where farmland gives way to scrub and rain forest, in search of one of the world’s most magnificent and endangered birds: the Philippine eagle, dubbed “the world’s noblest of flyers” by aviator Charles Lindbergh. Accompanied by biologist Jayson Ibanez, field research coordinator for the Philippine Eagle Foundation (PEF), I’m on a six-day expedition to investigate how the fate of this rare species intersects with the lives of farmers like Balicao.

With a 6.5-foot wingspan, the Philippine eagle soars over forests where—in a country naturally free of leopards and tigers—the bird is top predator. On two previous forays into Philippine eagle country, I’ve twice seen the raptors in the wild, admiring their steely bluish-grey bills roughly the size of my hands and claws that could almost encircle my neck. The Philippine eagle is one of the world’s three largest eagles (the others are the harpy eagle and Steller’s sea eagle). And it is the only bird of prey with blue-grey—as opposed to yellow, orange or brown—eyes. Known to live on just four of the country’s islands, only about 500 pairs of the eagles exist today.

Philippine Eagle Convert

Based on news reports from afar, Mindanao appears to be a hotbed of insurgency. Though the situation has been fairly calm lately, Philippine army posts have been notified I’m heading upcountry. En route to Sinaka, we stopped at a bus terminal where nine people were killed by a bomb a few years ago. Everyone I meet seems friendly, yet the notion terrorists are not far off is both novel and frightening.

Today, however, it is nature that causes problems for us, as moist winds bring swirling mists and drenching rain. Balicao and Ibanez lash a tarpaulin to a framework of sticks for shelter and we huddle beneath it, watching nearby trees sway. With eagles seeming distant as dreams, I ask Balicao about his life and his connection to Philippine eagle conservation.

Today, however, it is nature that causes problems for us, as moist winds bring swirling mists and drenching rain. Balicao and Ibanez lash a tarpaulin to a framework of sticks for shelter and we huddle beneath it, watching nearby trees sway. With eagles seeming distant as dreams, I ask Balicao about his life and his connection to Philippine eagle conservation.

Short but solidly built, with a macho moustache and machete in a wooden sheath hanging from his string belt, 46-year-old Balicao is a tough outdoorsman. As a slash-and-burn farmer, cutting trees so he could plant maize, he once lived a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence. Then, in the early 1990s, he saw a PEF poster in his village offering 3,000 pesos (US$50) to anyone reporting a Philippine eagle nest. In 1995, he found one and called the foundation. A PEF team visited, verified the nest and paid Balicao his reward under the group’s adopt-a-nest program. It also launched a community-based project aimed at restoring eagle habitat whilst helping farmers by providing native fruit trees as a future source of steady income to replace maize farming.

Balicao planted some 150 seedlings in the forest and now harvests fruits such as durians—foul-smelling, but hugely popular fruits with a custardlike texture—earning more than he did from corn. “The trees bring fresh air,” he says. “It’s cooler, and we can drink the stream water” because trees, unlike maize, prevent the erosion that once silted streams. The trees also help the eagles. “When I see a Philippine eagle, I’m happy,” says Balicao. “If not for the Philippine eagle, this project would never have happened. Now, I try to convince other people to protect the eagle.”

Rare Sighting

After a night in a wooden cabin, we awake to a sparkling, clear morning: good conditions for eagles, says Ibanez. Heading for higher ground, we walk through maize fields—a stark reminder that Mount Sinaka, one of the last bastions of the Philippine eagle, is also inhabited by a growing number of people.

At a vantage overlooking the head of a valley—with forested slopes on three sides—I raise my binoculars to scan trees and sky, but there’s no sign of an eagle. “We might do a ten-day survey, and have four days with no eagles, then a good display,” says Ibanez. It is not surprising, then, that no one knows just how many Philippine eagles survive in the wild. The 500-pair estimate is based on sparse sightings extrapolated to a possible total. Ongoing surveys by Ibanez and his colleagues should improve estimates.

A movement catches my eye. A large bird glides past on our left and vanishes into the trees. Ibanez sees it too, but is not sure if it’s what we are hoping for—until he hears a plaintive whistle from the trees where the bird vanished. “It is a Philippine eagle!” he exclaims. “A juvenile.”

The bird’s age surprises Ibanez, who has studied the Mount Sinaka eagles since 1999. Juvenile eagles usually leave their parents after 18 months, yet this one is older. Its whistles go unanswered, and the eagle circles above a clearing—looking massive even several hundred feet away—before cruising down into the valley, then gaining height and drifting over the ridge. “I still get excited when I see eagles,” Ibanez says.

Gaynawaan: Hope

We leave Mount Sinaka, riding pillion on motorbike “taxis” to cross a small river, bump along a dirt road winding through the rolling landscape, and arrive at a village of wooden houses with neither electricity nor running water to find a camp established by Ibanez’s field research team. The camp is by a strip of partly logged forest that is now protected by the local government. Although it has been more than a decade since an active eagle nest has been spotted here, the forest remains an important hunting ground for the raptors. And with the Philippines ranking seventh worldwide for endemic vertebrates, protecting the eagle’s habitat helps safeguard a host of mammal, bird, reptile and amphibian species found nowhere else.

Ibanez spends much of the night helping researchers disentangle bats from nets—the animals scream like squeaky plush toys until released—but the next day he still seems energized as he drives to our next destination. Passing through farm and grassland, Ibanez tells me about a new foundation project that will include the area’s first biodiversity survey and the establishment of corridors to link remnants of remaining forest. The project is called Gaynawaan—the local word for hope—and the World Bank has provided US $41,000 for its first two years.

The project spans ten rural communities, turning Ibanez into a part-time politician, lobbying local leaders to protect eagles. We call in at the office of Romulo Tapgos, mayor of a municipality hosting an eagle nest site. “When I was a little boy this area was full of trees,” he says. That may again be the case, as indigenous people move away from cash crops toward traditional tree-based agro-forestry. Tapgos is hoping that the resulting wildlife habitat will lure more Philippine eagles—as well as paying tourists who want to see them.

Flagship Species

It’s dusk as we turn onto the road to Mount Apo, a volcano that’s the Philippines’ highest mountain. Swathes of forest here make it an eagle stronghold. Apo is also the birthplace of the PEF, which grew out of a small captive-breeding project in 1977-1980, after a purely rehabilitation project that started in 1976 shifted to trying to also breed birds [success took some years]. The early years were tough, when fighting between government troops and rebels forced staff to relocate the project to the foothills. But an eagle was at last hatched in captivity, and the foundation began attracting more support and rearing more eagles. In 2004, PEF for the first time released a captive-bred eagle into the wild.

Soon after returning home, I learn that the eagle, which the researchers named Kabayan, had died of electrocution after landing on a grounded electric post. But further messages from the foundation contain happier news, including a 13th birthday party for the first captive-hatched eagle and fresh discoveries of eagles living in the wild.

I reflect on a conversation I had with Ibanez two years ago, when he suggested that despite the foundation’s conservation efforts, the Philippine eagle was doomed due to the government’s ambivalent forest conservation policies. But after shifting his focus from pure research to working with local people, Ibanez now believes there is hope for the bird.

“The Philippine eagle can inspire communities,” he says. “We are using it as a flagship—and we’re not only saving the species, we’re also improving the lives of Filipinos.”

This article appeared in National Wildlife magazine.

Philippine Eagle Foundation website

Philippine Eagle Foundation wins accolade from Yale

Richly deserved award: