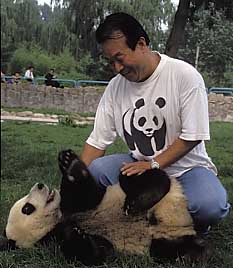

In a cave near a tributary of the Youshui River, Pan discovers Jiao Jiao, an eight-year-old, 80-kilo panda, one of thirty he has been studying for up to six years. In her arms, tiny as a mouse, is her baby, its pink skin showing through its sparse fur.

In a cave near a tributary of the Youshui River, Pan discovers Jiao Jiao, an eight-year-old, 80-kilo panda, one of thirty he has been studying for up to six years. In her arms, tiny as a mouse, is her baby, its pink skin showing through its sparse fur.

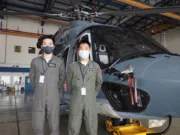

Squeezing towards the cave, his arm outstretched to her, Pan inches closer to Jiao Jiao. He has come to know her well, and now the panda, exhibiting amazing trust, allows him to gently stroke her dense fur. It is a joyous, unforgettable moment for the 55-year-old scientist who has devoted his life to saving these endangered creatures.

Pan and his research team named the days-old, female cub Xi Wang – Hope – the wish they hold for the future of pandas. Since her birth in August 1992, Pan has continued his Qin Ling study, which has been called China’s best panda research program by George Schaller, science director of the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society and author of The Last Panda. Pan’s findings have expanded the world’s knowledge of the panda and its ecology, overturning some long-held notions about panda behavior and focusing the world’s attention on the plight of the panda.

David Melville, executive director of the World Wide Fund for Nature Hong Kong, which funds the Qin Ling study, says Pan and his research “have contributed greatly to panda conservation.” Three years ago, Pan was awarded the Order of the Golden Ark by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, for his unrelenting efforts in fighting for the pandas, including initiating a successful petition to China’s President and Premier for a logging ban in a panda habitat.

Pan’s work with pandas is rooted in his boyhood dreams. Born in Bangkok in 1937 to fifth-generation Chinese immigrants, he moved with his parents to Shantou in Guangdong province when he was three. He loved hearing his father’s and grandfather’s animal stories. Later, he read Darwin’s diaries and was riveted by the notion of traveling and making scientific discoveries.

As a biology student at Peking University, Pan encountered the world’s first captive-born panda during a visit to the Beijing Zoo. Holding the lively 13-kilogram infant, he was captivated. When he learned how close they were to extinction, he knew he had to help these engaging creatures.

The giant panda once ranged from Burma through much of eastern China. Over hundreds of thousands of years its range shifted from the tropical and subtropical climates to the more temperate forests of Central and Eastern China. Over 2000 years panda fossils had been discovered in at least thirteen provinces, but by the latter half of the twentieth century, pandas existed in just three – Sichuan, Gansu and Shaanxi. Hunted by man, their habitat shrinking, panda numbers had declined to about 1200.

In 1980, Pan, now a zoology lecturer at Peking University, volunteered for a panda research program conducted by the WWF and the Ministry of Forestry at the Wolong Nature Reserve, Sichuan province. Fearing the extinction of the panda, the Chinese government had started establishing panda reserves since 1963. But even in these the panda sometimes suffered from poaching. Some conservationists had concluded that the panda would perish unless man came to its rescue through captive breeding programs. Pan soon found himself in disagreement with some of his scientific colleagues.

Pandas were known to feed almost exclusively on bamboo, and researchers working in Sichuan had found that they favored the leaves and young stems of the arrow bamboo. However, once every 45 to 50 years, the arrow bamboo flowers and dies off over wide areas. It takes a decade before new plants, spawned by the flowering, mature. When news came in of arrow bamboo flowering in 1983, the government made plans to “rescue” starving pandas and place them in specially constructed holding stations.

To fund the rescue, appeals were made worldwide. Touched by reports of bamboo die-off and starving pandas, people sent donations. But Pan reasoned that pandas had survived countless flowering events and would not suffer unduly because they could eat other bamboo species. The rescue plan, he believed, would traumatize the animals, posing a high risk of death. He spoke out against the rescues openly even though it could jeopardize his career.

“If we don’t say bamboo flowering is a very serious problem, we can’t get international donations,” a bureaucrat told Pan. But Pan persisted, feeling he owed it to the pandas, and to the schoolchildren and others sending money. He sent a lengthy report to the State Council. Eventually, the government halted the rescue operation. Even so, by then 108 pandas had been captured, of which 33 had died. Pan’s argument that bamboo flowering and die-off was not a deciding factor regarding pandas’ survival was later confirmed by field observations. Meanwhile, Pan had found his life’s work – helping pandas survive in the wild.

In 1984, Pan left Wolong to conduct his own panda research in the Qin Ling Mountains and later shifted his study to a forest that was managed by a timber unit. Pan and his crew paid team expenses from their own pockets, augmented by small donations from Pan’s brother and sister in Hong Kong. He and his colleagues lived on rice and potatoes. Pan missed his wife and two small daughters terribly. Several lean years would pass before Pan’s work began to receive recognition and funding grants.

Because visibility in bamboo forests is poor and pandas are shy, Pan at first got only rare glimpses into the lives of the creatures. It was not until 1987 that permission was granted to put radio collars on the pandas, making it easier to locate them.

Jiao Jiao (a name meaning “Double Charm”) was among those collared by Pan’s team. In the spring of 1989, Pan reckoned she was four and a half years old: just mature enough to breed. So when in August the same year Jiao Jiao entered a cave and stayed put for several days, he suspected she had given birth. Peeking into the cave from the top, Pan glimpsed her with an infant. After nine days in the cave Jiao Jiao made a foray to hunt for food. Pan and his team examined the infant. It was a male, which they called Hu Zi – Little Tiger.

Jiao Jiao, who would become one of the world’s most studied wild pandas, moved Hu Zi to a succession of caves. At five months and nine kilograms, Hu Zi left the caves for the forest, where Pan often discovered him up a tree while Jiao Jiao fed nearby. Pan regularly weighed Hu Zi and monitored his health but kept a safe distance from Jiao Jiao, who’d once charged at him and Lu Zhi.

Gradually Jiao Jiao became accustomed to the researchers. “Jiao Jiao, we’ve come to study you, not to harm you,” Pan would say as he approached. Hu Zi followed his mother everywhere, eating the bamboo she ate and scent-marking where she scent-marked. A loving mother, Jiao Jiao presented Hu Zi with toys, such as an old metal washbasin, and let him try to suckle even after he was weaned at 13 months. But in spring 1992, Jiao Jiao mated, became pregnant, and drove off her first born. Hu Zi, who now weighed about 70 kilograms, took to following an older male. Jiao Jiao gave birth to Xi Wang that autumn.

As the study continued over the years, Pan and his team gained or confirmed many insights into panda society. Most satisfying is the discovery that pandas are polygamous. Researchers previously thought that a dominant male won breeding rights, but female pandas in Pan’s study group have mated with four or more males in a season.

Conservationists can feel especially buoyed by Pan’s study about panda fertility. While pandas have proven notoriously tough to breed in captivity, Pan has corroborated that they can reproduce well in the wild. After the gap of three years between Hu Zi and Xi Wang, Jiao Jiao has given birth to one infant every two years. Says Pan, “As captive pandas are known to be fertile at 20, a female panda could rear perhaps eight young.” DNA tests on pandas in the wild have revealed a good genetic diversity.

“The Qin Ling population is pretty stable,” says Pan. “Among the 36 pandas we’ve closely studied, we’ve seen seven deaths and 13 births, with 11 surviving infants.”

Pan has discovered a mutual accommodation between farmers and pandas. Pandas typically spend the summer months in the alpine zone at 2400 to 3000 metres, dropping down to between 1350 and 2400 metres in winter. “Permanent agriculture has proven impossible at these altitudes,” says Pan. “So while the lower Qin Ling is mostly farmland, the area above 1350 metres is like a panda refuge.”

Can the panda be saved? Pan believes so. All it takes is bamboo forests and peace and quiet. Threats to the panda’s habitat are an ongoing concern. During 1993, timber cutting intensified in Pan’s study area. Once more daring to speak out for his beloved pandas, Pan wrote directly to President Jiang Zemin and then-Premier Li Peng, urging that the logging be stopped. Not only was a halt to the timber cutting ordered, but in 1997 the Chinese government designated 305 square kilometers of Pan’s mountainous domain a panda reserve – making it one of the prime sanctuaries for the giant panda. About 170 of the Qin Ling’s 240 pandas are now in protected areas.

On the other hand, the Chinese government, in cooperation with WWF, is also implementing a plan to boost protection of the 13 existing panda reserves and to create 14 new ones.

Poaching is another threat. Seven pandas have been lost to poachers in the Qin Ling Mountains in the past 14 years. About ten years ago, wildlife trade investigators found panda pelts selling for up to US$10,000, allegedly to wealthy expatriate Chinese as well as buyers in Taiwan and Japan. The Chinese government has since introduced legislations stipulating that poaching or dealing in pandas are criminal offences.

In August 1997 Pan made a short visit to the Qin Ling study area, expecting most pandas would be in their summer ranges on the high slopes. With him were 13 undergraduates who planned to study how the ecology had changed since logging ended.

During the night, Pan heard slow footsteps and breathing noises outside his room. That’s strange, he thought. Why has a panda come down from the mountains? The next morning, Pan found Xi Wang standing in front of his door, as if she’d come looking for her old friend. Several days later she went back into the hills and gave birth to her first cub.

In August 1998, a new member joined Pan’s study group. He received a message from one of the students at the study site: Jiao Jiao had been seen with her latest, fifth infant – Xiao Wu.

[This article first appeared in the February 2000 Chinese edition of Reader’s Digest. Reader’s Digest holds copyright in the text.]

Top People

Helicopter crews brave mighty winds and waves to rescue seamen during South China Sea typhoons

On the morning of 2 July 2022, as Hong Kong was lashed by gales and rainstorms…

James Reynolds typhoonhunter and volcano videographer

James Reynolds is a pioneer of travelling to film typhoons, and has added volcanoes to his…

Maasai safari guide Jackson Looseyia

Kenyan born Maasai safari guide, one of the presenters of the BBC’s Big Cat Live series.

A Man for All Sequences Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger made pivotal contributions to studying the chemistry of life, primarily by finding how molecules…

Blue light at last wins Nobel for LED titans

Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura received a Nobel Prize for seminal roles in the…

Genius of the Jungles: Alfred Russel Wallace

Though best known as co-discover of evolution, Wallace was an astonishing man: an explorer, self-taught naturalist,…

The butterfly and the remarkable Professor Hofstadter

Hofstadter’s butterfly, a remarkable spectrum of electron energy levels, was first described in 1976 by Douglas…

James Hansen Godfather of Climate Change retires yet will be very busy

Instead of aiming for a leisurely life after work, Hansen plans to better focus his time…

Jill Robinson helping bears

First Jill Robinson was shocked, then she set out to stop the suffering The Great Bear…

Jessie Yu – Hong Kong Single Parents Assoc founder

The best way to get ahead, says this tireless Hong Kong philanthropist, is to help yourself.…

Keeper of the Kings: Captive breeding Philippine Eagles

Domingo Tadena: Captive breeding Philippine eagles

Dr Yang Lihe helping former leprosy patients

Yang knew only too well that the suffering of leprosy patients doesn’t end when the disease…

Dinosaur hunter Dong Zhiming

Meet the world’s greatest dinosaur hunter.

Dramatic rescue by brave helicopter crew from roof of blazing Garley Building in Kowloon

A helicopter crew rescues people from the roof of a burning building in Kowloon.

Mountain Dog and rebuilding schools in China

Retired Hong Kong schoolmaster helped get many kids from poor families in China back into the…

Mother Ko’s fight for justice

The more lawmakers ignored her, the more determined she became to seek justice

SARS doctor and heroine Yannie Soo

A mysterious illness was striking the medical staff down one by one. How could they fight…

Allen Lien

In October 2002, boxes of clothes began arriving in Burkina Faso, a country in West Africa,…

Teacher Lin helps kids in Taiwan

From reading and her observations of people, she believed everyone had good in them. These kids…