Lots of Places You Absolutely Want to Go

Daybreak in western Yunnan. Clouds are tinted pink by the sun, rising over hills bounding the eastern horizon, beyond Erhai Lake. Below us, by the near shore of the lake, Dali Old Town is awakening.

Yet we have no time to dilly-dally and admire the scenery. I’m with Xi Zhinong, China’s best-known wildlife photographer, and he’s intent on finding spectacular gamebirds – Amherst’s pheasants – in woods just above his home.

Xi drives up a twisting dirt road, intently watching for movement. He sights a pheasant just ahead, and stops the car. It’s a splendid male, with white belly, shining blue upperparts, a black and white shawl from head to shoulders, and a billowing, 80cm long silvery tail.

I grab photos, and the pheasant strolls away, using skills a ninja would envy to merge into the forest. By breakfast, we’ve seen 12 pheasants. Then, it’s time to explore more of the area in and around Dali with my family and friends.

It’s almost 30 years (wow – 30 years!) since I first came to Dali, and I’m intrigued to see how much has changed since. There’s a new city of high-rises burgeoning south of the lake, but the old town – the “Dali” that draws tourists – retains its charm.

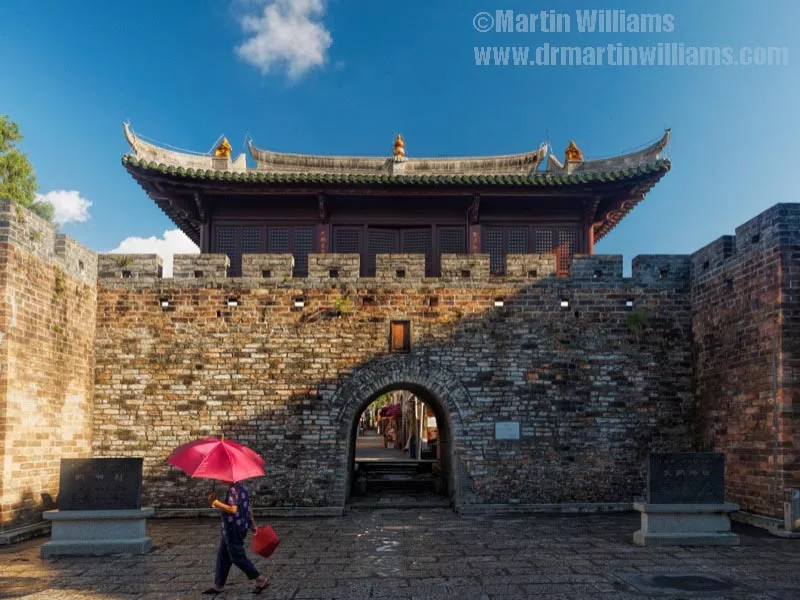

With remnants of defensive walls, plus gates through watchtowers on each of its four sides, the old town’s design reflects the region’s tumultuous past. For over five centuries from 737, the Dali area was the hub of the Nanzhao and then the Dali kingdoms. Mongol forces invaded in 1253, destroying the capital and palace, and it wasn’t till the 1400s, during the Ming Dynasty, that Dali city was rebuilt on the current site.

A laidback atmosphere pervades the streets. Even the traffic is subdued, and along pedestrian-only lanes between two-storey buildings there’s almost a hippy vibe, with mainland China tourists taking time to soak up the local culture, investigate locally made souvenirs, listen to guitar strumming street performers. Hong Kong tourism officials might be aghast at the thought there’s no international brand store in sight, and instead of swanky eateries there’s a myriad small restaurants, along with barbecue stalls and a cafe offering “Coffee, Cake, Fruit juice plus lots of things you absolutely want to have”.

Outside Dali, the village of Xizhou has a small car park beneath tall trees with nesting herons, from where visitors stroll to a square ringed by restaurants and stalls selling ornamental cloths and clothing dyed in traditional style. A map shows a place for cormorant fishing nearby, but we find there’s an entry fee of over 100 yuan – too much, I think, for a quick look at men using these birds to catch fish in Erhai Lake.

Along with cormorant fishing, I remember seeing Dali’s Three Pagodas on my first visit; but here too there’s now a pricey entry fee, plus a huge, new encircling wall. So we give it a miss, instead favouring a cable car part way up the Cangshan mountain range that soars above Dali. We ride to a small gorge, where a spring feeds a crystal clear pool, then walk down beside the steam, through a valley with flowering shrubs.

Transportation has greatly improved since my first visit, and we take a six-hour bus ride northwards, to Shangri-La, to spend five nights in an area that was part of Tibet. The town’s name used to be Zhongdian, but officials changed it in a bid to attract more tourists, luring them with the appeal of a fictional land described in James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon. I came in 2002, soon after the renaming, and found there were indeed similarities, including deep gorges with warmer climes low down, a majestic monastery, and a mighty snowy peak. This reflected Hilton basing Shangri-La on the writings of Joseph Rock, who explored here early last century.

While it’s disappointing to find the monastery has become a tourist trap, Shangri-La still abounds with fascination and wonder. There’s an old town here, too, with a warren of shops, restaurants and hostels below a temple on a small hill, and finishing work underway for new houses with wooden facades in an area that was last year ravaged by fire.

China’s penchant for cable cars has reached Shangri-La, and we ride to near the summit of 4449-metre Shika Snow Mountain. Appropriately, there’s a late spring blizzard raging as we reach the topmost station, so even stepping briefly out of a doorway is challenging. Photos show that on fine days there’s good hiking here.

Shangri-La town is near Napahai, an upland lake ringed by Himalayan peaks. Though around 3260 metres above sea level, it doesn’t freeze in winter, when it attracts thousands of waterbirds. Helped by Jia Xi, a forthright Tibetan man who runs a guesthouse by the lake, we find geese, ducks, and globally endangered Black-necked Cranes – elegant birds around 1.3 metres tall, with wild, bugling calls.

Bulkier Himalayan and black vultures are gathered near the lake one morning, preparing for a day of watching in case one of the grazing horses, yaks and cows falls ill.

We take a day trip to Balagezong, in a 3000-metre deep canyon between precipitous peaks. It’s in a national park, and a bus for visitors’ tours leads to a place where a walkway bolted to a cliff winds above a fast-flowing river. There’s also the most startling set of hairpin bends I’ve ever encountered, the bus making abrupt turns as it climbs to a spur topped by a Tibetan village.

Leaving Shangri-La, we drop down from old Tibet, but are still amidst mountains. At Tiger Leaping Gorge, we mingle with busloads of tourists admiring the Yangtze as it thunders past and over boulders beneath towering, snow-capped summits.

The First Bend of the Yangtze is far more peaceful, with only a handful of others visiting to see where the mighty river turns from its southward course, and heads east instead.

There’s a roadside store, where people of the Naxi minority have gathered to play cards, rest and chat. Such scenes were long commonplace here; I found the old part of nearby Lijiang similarly imbued with community spirit during a visit in 1986. But a decade later, Lijiang was devastated by an earthquake, and though the “old town” was rebuilt it became as sad and soulless as Lantau’s Ngong Ping 360 village.

We visit on our last evening, finding a myriad shops but no sign anyone lives there nowadays. Loud music bars with bright lights, DJs and dancing girls line central streets. Though it has World Heritage status, the “old town” seems besotted with money-grubbing.

While its fate is lamentable, there is a useful message here: if you’d like to experience the charms of northwest Yunnan, better visit sooner rather than later.

Written for and first published in the South China Morning Post magazine.