Our memories play vital roles in defining who we are. Yet can you really trust your memory?

Our memories play vital roles in defining who we are. As you recall your childhood, you might smile now at the minor tragedy of dropping an ice cream cone, remember the determination as you started cycling for the first time, and perhaps still feel the fear of being lost in a shopping mall when you were only five, contrasting with the thrill of a ride in a hot air balloon.

Though it’s difficult to calculate the brain’s storage capacity, Paul Reber –professor of psychology at Northwestern University, US – estimated it is around 2.5 petabytes. He noted that this would be enough to hold enough TV shows on a digital video recorder to watch continuously for more than 300 years.

But as you’ll already be aware, your brain does not function like a video recorder, and you can’t simply “watch” memories continuously. Sensory information – like things you see or hear – is stored for fractions of a second, perhaps moving into short-term memory, where around seven items might be retained for half a minute. Then, long-term memories form through encoding information in a process that may be heightened by your emotions: if you’re scared by someone pointing a gun at you, you might remember the gun but not his or her face.

Several science fiction tales are based on the mysteries of memory. For instance, in the movie Inception a team of corporate spies infiltrate people’s dreams to discover information and plant false memories. Last month came a report that a team of scientists had indeed introduced a false memory – albeit in mice, and without joining their dreams.

The mice were genetically engineered, so that when forming memories in cells within the hippocampus they would create a light sensitive protein. They had also been implanted with optic fibres that could deliver pulses of light to their brains, which could cause this protein to reactivate the memories.

The mice were placed in a safe chamber with distinctive features, where they behaved normally. Then, they were moved to another chamber with different features, where their feet were subject to a mild electric shock. As the shock was applied, light was shone on their brains, to activate the memory of the safe chamber.

Next, the mice were placed back in the safe chamber. They froze in fear, showing they had a false memory of receiving an electric shock there.

In their paper on the results, the researchers mentioned “engram-bearing cells” – which is a reference to the neural networks that may hold individual memories. The research builds on evidence that engrams are physically real, and though we are far from being able to use them to split up business empires there are some parallels to Inception.

“If you want to grab a specific memory you have to get down into the cell level,” Dr Xu Liu, a lead author of the study on mice, said in a report by BBC News. “Every time we think we remember something, we could also be making changes to that memory – sometimes we realise, sometimes we don’t. Our memory changes every single time it’s being ‘recorded’. That’s why we can incorporate new information into old memories and this is how a false memory can form without us realising it.”

Photos and false memories

Other researchers have shown that there’s no need for brain implants and electric shocks to create false memories. Instead, they can be formed in people with little more than stories and photographs.

Professor Elizabeth Loftus, of the University of California, US, is among premier researchers on false memory, and was recently honoured for her work by receiving the American Psychology Foundation’s Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology.

Loftus entered the field through examining eyewitness testimony, and finding that the nature of questioning affected the “facts” that people recalled. Later, prompted by a case involving a woman who apparently remembered repressed memories of her father raping and murdering a childhood friend, she began investigating whether people could “remember” entire events that never happened.

In one experiment, Loftus asked 24 students about four childhood experiences – three of which were real, and supplied by a family member; one of which was false, involving them being lost during a shopping trip. Seven of the students remembered being lost, with some even supplying extra details.

Photographs can also play a role in inducing false memories. Researchers at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, showed individuals in an experiment a doctored photo in which they appeared to be taking a hot air balloon ride during childhood. Asked to remember details of the trip, fifty percent of participants developed at least partial memories. A later experiment found that stories of the trip were more effective than photos in creating false memories.

Also – editor please take note and add a picture to this column! – there is evidence that people are more likely to remember a newspaper story if it is accompanied by a photo.

Deleting and obscuring memories

Sometimes, we might wish to forget things. And evidence is emerging that this might be more readily accomplished than anyone expected. In the late 1990s, Karim Nader – now a professor in the department of Psychology at McGgill University, US, found that rats given a drug suppressing protein synthesis before recalling a scary memory evidently did not re-store the memory. This has led to tests with people recalling horrific incidents whilst given medication to reduce emotions, and then finding the memories less stressful. Though some experts including his supervisor thought Nader’s early experiment unlikely to succeed, he won a Nobel Prize for his research into memory. “The fact that memory turns out to be far from permanent is a positive thing for human survival,” he remarked to CBC News.

In spring this year came the results of a study that found people formed fuzzy long-term memories of a video, if within hours after watching it they were given a summary peppered with misinformation.

But mostly, of course, we want to boost memory, not impede it. And here, a study reported this month might gladden your heart, for there’s no need to take strange medicines. Instead, for better memory, just drink two cups of cocoa a day.

Published in the Sunday Morning Post.

Further reading includes:

The fiction of memory: Elizabeth Loftus at TEDGlobal 2013

Early warnings of climate change

While climate change resulting from human activities might seem a new-fangled concept, there have been on-point predictions dating back many years.…

Ignoring Science Makes Global Climate Disaster as Inevitable as Titanic Submarine Implosion

Climate change has been prominent in worldwide news this summer (2023), notably as we have just lived through the hottest week…

Have you been bullied into health? Fear, quackery and Covid

So here we are with our modern-day wonder, the internet – where even with a smartphone, you can search for and…

Never mind the antimask-o-sphere. Science shows face masks help reduce Covid spread

Just had one of those silly Twitter “conversations” with someone who had position so fixed, impossible to change with facts. Yeah,…

A Covid scrapbook: snapshots from the crazy pandemic

I’ve read accounts of the Spanish Flu, which was the last major pandemic, mainly in 1918 [so over and done with…

Highly pathogenic bird flu variants mostly evolve in intensive poultry farming

Highly pathogenic bird flu variants evolve from regular, low pathogenic, bird flus, within intensive poultry farming.

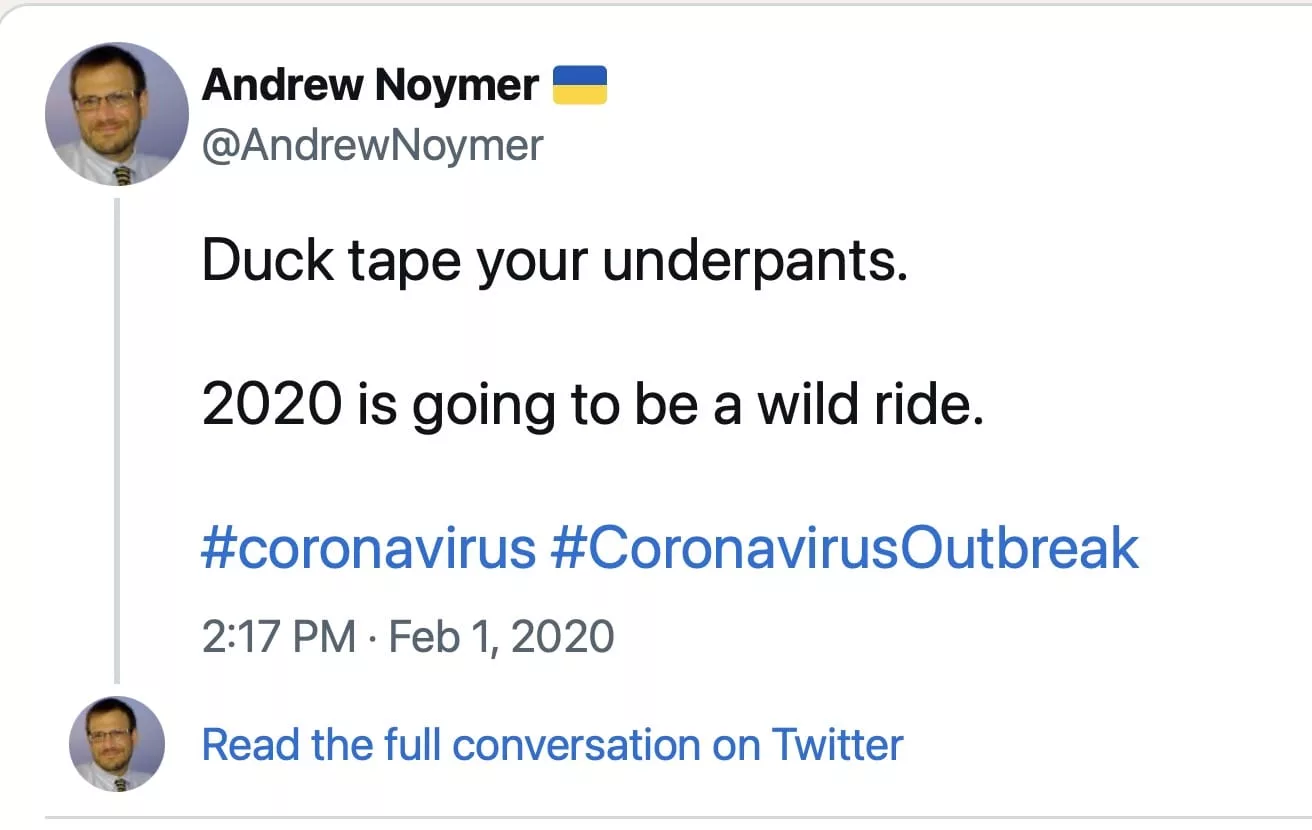

Keep Your Underpants Duck Taped and Air Clean as Covid Wild Ride Continues

We’ve learned a lot about Covid, even developing vaccines. Yet Covid remains an issue, no matter how much we might wish…

Covid is airborne so ventilation and air filtration are important

Since early in the pandemic, I’ve been seeing scientists arguing Covid is airborne, even with hashtag #covidisairborne – including to counter…

Long Covid – info and links indicating major impact

Evidence is snowballing that Long Covid is also a serious issue, even affecting people in whom the disease initially appeared mild.

Perhaps Covid arose through lab leak of tweaked bat Coronavirus

Maybe humans tweaked bat coronaviruses in gain of function experiments, inadvertently creating Covid thro lab leak.

The Covid Conundrum: Endless Lockdowns, Let It Rip … or What?

Covid is airborne, which means that much as unprotected sex is a risk for HIV, unprotected breathing might result in Covid.

Science shows Covid including Omicron is Really Not the Flu

Some of the science showing Covid including Omicron is a huge issue; and one that looks set to be with us…

“Alarmist” Covid predictions outperform Covid deniers’ soothsaying

The disinfo downplaying Covid is often from rightwing, mainly money-minded folks who perhaps don’t care too much about actual people.

Covid virulence, vaccines and variants

Science can provide some insights into what may happen with Covid, along with ways to limit its impacts.

We’re in the Covid Era for the Long Haul

We’re in this for the long haul, with the virus like a relentless, invisible foe, ready to exploit errors, slip through…

My Strange n Surprising Summer Staycation with Cellulitis

rom quick pricking by unseen marine creature, to intense fever, and hospital stay for an infection deep within the skin.

Covid virulence, vaccines and variants

[Written for South China Morning Post on 6 January 2021] In January last year, as reports were emerging of the new…

The Viral Time Bomb – Pandemic of Our Time

Guan Yi, director of the State Key Laboratory of Emerging Infectious Diseases at Hong Kong University, has extensive experience of viruses;…

From China With Fear: the Wuhan Coronavirus Won’t Kill Us All

As news of Wuhan coronavirus emerges, evolutionary biology suggests potential for a pandemic, not killing high percentage of people.

Fightback Needed as Science and Life Support System Under Attack

Environmentalism is under assault; yet this planet is the only home we have; providing our food, air, water… It’s our life…

Secret World of Hong Kong Water Supply

Hong Kong’s water supply system has been vital to its development as a “world city”.

Hong Kong Belching Buffaloes n Bubbling Paddies and the Mystery Methane Rise

Prof Euan Nisbet leads a science team to Hong Kong in quest to help find why levels of potent greenhouse gas…