Our boat nudges the pier, then pauses against the one flight of steps, a prow-mounted tyre stopping concrete scraping on wood. We clamber ashore, check we have all our gear, and the boat leaves. With neither sight nor sound of anyone here, we could be as lonesome as castaways. But then, the place is no longer welcoming. Filing off the crumbling pier, we pass a red sign with the words `Danger; Blasting; Keep Out’ painted on in white.

We soon halt, to leave rucksacks, tents and food we will not need till later among the trees; to protect against ants, bags with food in are hung from branches.

A laughingthrush shrieks among the undergrowth, its brief outburst only emphasising the deceptive quiet of our corner of Chek Lap Kok. Central, the main business district of Hong Kong, lies only 22 km to the west, but seems as remote as the Moon. We have arrived to spend an afternoon and evening scouring parts of the island for wildlife, especially reptiles and amphibians. Already, wildlife has discovered us: mosquitoes dance around arms and legs, prompting liberal applications of repellent.

Our team is small: leaders James `Skip’ Lazell and Numi Goodyear, research assistant Suzanne Ayuazian, volunteers Carol Elliott, Jane Herd and Connie Hastert (all members of Earthwatch, an organisation supporting fieldwork worldwide), and me. Lazell and Goodyear are from the US-based Conservation Agency, which was founded by Lazell. Through the agency, the two pursue their love of investigating, and helping to protect, animals ranging from rodents to flying lizards. Their globe-trotting research has taken them to such far flung places as Hawaii, the Philippines, Australia, Brazil and China.

Hong Kong was originally rated by them as little more than a transit lounge en route to China; but red tape and rising costs in the People’s Republic made them reconsider, and they made a first survey in 1987. It was a great success: Lazell describes the territory as a `biological treasure trove’, and has since made annual visits, which he plans to continue until at least the handover to China in 1997. Last year, Lazell shifted the focus of the research to cover the areas which would be destroyed by the scheme to build Hong Kong’s new airport. Chief among these was Chek Lap Kok, which will be levelled to make way for runways, leaving only a token hill. The demolition work is now underway, and this is the last survey Lazell and Goodyear will make on the island; when they return to Hong Kong next year, it will have been blasted flat.

Who wants a snake bag?

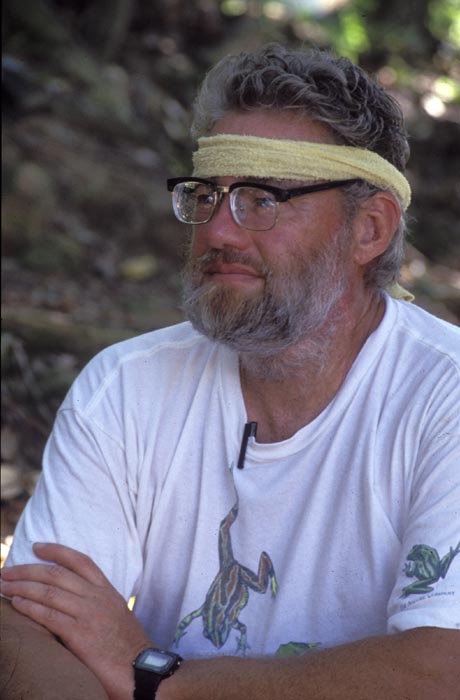

`Who wants a snake bag?’ asks Lazell. Don’t look at me, I think; I’m here as fly-on-the-wall-cum-photograher, and not planning to catch any snakes. Lazell ties the strip of towel that serves as sweat band around his forehead, stuffs the pillow case more technically known as snake bag into his belt, and we set off.

Fittingly, Lazell and Goodyear take the lead. As so often, they discuss herps — as herpetologists call the reptiles and amphibians they study. The two might talk of taxonomy — should two similar creatures be regarded as different species, should certain species be classed together, or separately? Or of conservation work. Or sometimes they have The Argument. Which is really just contradiction, about an iguana. Goodyear says one thing about where it can and cannot live, Lazell another, and the two meet the next morning barely able to say `good morning’: Lazell sullen, maybe a little embarassed; Goodyear still fuming.

The path gives out, and we push along the edge of an overgrown field. Goodyear hacks at the tangled vegetation to clear some kind of trail. Lazell spies an overturned canoe amongst the grass. Could be a herp or two under it, so the team pulls away any plants that are trying to hold it in place, grabs at the broken hull, then lifts and shoves it out of the way. Not a herp in sight.

But a farmhouse we soon reach does have herps. The human residents have gone — last year, the island’s houses, store rooms and even pig pens were posted with notices saying `this area will be cleared/required for permanent development in about March 1991′ — leaving behind a photo album, rusting tricycle, and bits of junk. The junk catches Lazell’s eye. Especially the larger pieces, which he lifts and throws to one side, to see if there is anything underneath. There are Chinese Geckos here — `chinensis’ the team members call them, and though several flee to inaccessible hiding holes, others are caught, and put in plastic bags.

After peering behind boards and seeing the tail end of one too many chinensis, I decide it’s time I caught a few. A young one, trying to hide among dead leaves, seems a likely candidate to get me started. Kicking through the litter with my boot, I finally corner and clumsily grab the unfortunate creature — which is maybe 5 cm long. Giving it to Lazell, I feel my legs being pricked as if by small needles. Ants — I must have kicked up a nest of them. I move round the corner, remove trousers, boots and socks, and hurriedly flick off and wipe away all those I can see. The others, meanwhile — young ladies included — are enthusiastically chasing geckos and grabbing them by the bagful.

I should have guessed. Last year, the volunteers in a survey team included two men who seemed very happy to let Lazell and co-workers do the grabbing (one had claimed to be an amateur herpetologist, but checked before making his first catch, a tiny frog, `this won’t hurt me, will it?’). Meanwhile, a young woman on their team dashed eagerly through the undergrowth after herps, and relished the thought of encountering something exciting, like a krait or a cobra (recognising a true believer, Lazell invited her along on further surveys with the agency).

But even believers have their limits. Leaving the farm, we take a track which leads down to the beach. Lazell finds more junk, and is keen to turn it over, but is told to hurry on out of the trees. Here in the shade, we have met a welcoming committee of mosquitoes, which swarm around us, eager to taste their first human blood in months. They keep low, and find ladies’ legs exposed by shorts make great feeding grounds, repellent or no. `Maybe I should have recommended wearing long trousers,’ Lazell says, and waits to be told he already did.

The beach offers respite, and chance to remove bite ends — barbed seeds that have got stuck in trousers, shorts, shirts and socks as we brushed through the vegetation.

This was the nicest island in the South China Sea

While the others paddle, or kick a football washed up by the tide, Lazell sits on a plank across a dried up stream, and gazes at the sea. On this final visit to Chek Lap Kok, he could be witness to the dying days of an old friend. `This was the nicest island in the South China Sea when it was still functioning,’ he says. `You could have mussels, fish, pork chops and pineapple for dinner. It was a great place to hunt (for herps), with some nifty species, and three conveniently located beer stops.’

With his bushy grey beard and weather worn features, Lazell has something of the air of an old sea dog who has seen too many ships lost at sea. But in his case, there have been too many environmental tragedies, too few successes. And when he looks to the future, he believes there is far worse too come. `Oh, it’s happening,’ he told a volunteer who asked about the Greenhouse Effect. `It’s happening and we’re not going to like it. We won’t like it when Los Angeles turns to dust and blows away.’

Lazell’s gloomy outlook has not, however, stopped him working to save wildlife. He had tried to upset plans for the airport, maybe halting it or ensuring habitats were saved — Hong Kong’s leading English newspaper, the South China Morning Post, ran a large feature based on his views — but the government was not to be swayed by him or anyone else (though his efforts did not go unnoticed; the Governor reportedly said `I don’t need Americans telling me what to do about the environment’).

Goodyear, who decided to paddle, offers a contrast in styles to Lazell. For one thing, at 35 she is younger. Lean, too, looking in need of a good meal (but try keeping up with her on a hike; even under midday sun, she pauses only to turn junk, drink and eat in a villager’s home-cum-shop, and wallow in the pool at the foot of a waterfall).

While Lazell is into herps generally, Goodyear prefers to select threatened species to study, and so develop action plans for saving them. On Guana, in the British Virgin Islands, she is working on the iguana that features in The Argument: she has trained one to come running out of the forest when whe calls (`Henry will love that,’ says Lazell — Henry is the millionaire owner of Guana, whose whims include preservation of his island’s wildlife). This summer, she trapped an anteater-like Pangolin over on Lantau Island, and tracked it using fluorescent powder and a radio transmitter: the results will help her draw up a management plan for releasing these rare animals into the wild.

Our rest over, we head back to the waiting gear, and leave the booty. Then, we strike up a different trail, to hunt in a small wood, and round another abandoned farmhouse.

Last year, the owners would not allow Lazell’s teams to search around their property. But with them gone, we have buildings and land to ourselves. And, as Goodyear says, `there is lots of satisfying junk to turn over.’

`Why didn’t I get something under that?’ asks Lazell, after pulling up a large piece of hardboard. `There’s some little thing here Skip, without a tail,’ he is told. `Oh yeah — a nice little bowringi,’ he says on checking. The bowringi — or Bowring’s Gecko — is duly placed in a bag. The geckos seem to be all bowringi here; the other farmhouse is the best place Lazell knows for chinensis.

Though not all the pieces of wood, bags, slabs of concrete and roofing material have herps under them, most reveal plenty of cockroaches, which dash for cover along with any geckos or skinks there may be. Sometimes, too, there might be a snake. Then, says Lazell, `You have to think fast.’ The thinking will include whether it is poisonous — snakes such as the kraits and cobras can be deadly — and, if so, whether you should grab it, and how. Experienced collectors like Lazell might grab snakes, but most of the volunteers are under orders to pin them down, using a stick or even a boot, and shout; `then we’ll come running.’

But we do not find any snakes here. Hastert makes an unwelcome discovery when she lifts a board and exposes a wasps’ nest: a few chase her, and one stings her arm. I notice the long, slender tail of a Changeable Lizard moving under the corner of a roof, and approach to find it sitting still, hoping we have not noticed it and will pass on by. Elliott picks it up, and it is duly placed in a plastic bag. It is, says Lazell, the first one found on southern Chek Lap Kok. And probably the last. Like the other herps collected today, it will be killed, pickled, and mailed to the United States. With the island doomed, Lazell sees no point in leaving creatures that might benefit research. Moving them elsewhere would not work, he says: `Where would you put them? The suitable habitats for these species are already full.’

Romer’s frogs

At dusk, we sit on the pier for a picnic dinner of tuna and mayonaisse sandwiches. We are joined by Michael Lau, a local herp zealot. He too arrived this afternoon, but has little to report. Right now, it is collecting after sunset that most interests him — since one of the creatures that emerge at night is Romer’s Frog.

Romer’s Frog is unique to Hong Kong. Indeed, for some years it was believed to be unique to just one island. It was first discovered in 1952, when amateur herpetologist John Romer found some in a small, remote cave on Lamma Island. The next year was also the last when Romer again saw `his’ frogs. Despite repeated searches over the next 30 years, he could find no more, and he died believing the species had become extinct. But Romer’s Frogs mainly lived outside, not inside, the cave, and they were rediscovered on Lamma in May 1984. Two years later, they were found on Lantau Island. And in 1990, Lazell’s teams found them on Chek Lap Kok.

Prior to Lazell’s work, the island was not known to host any rare species. Preparations for the airport had included an environmental impact assessment of sorts, with a section devoted to herps and other invertebrates that singularly failed to impress Lazell. `Not worth toilet paper,’ he railed. `Done by someone sitting in his office … includes some preposterous species.’ Preposterous species there may have been — like mountain-top snakes, on an island rising to just 110 metres — but there were no world rarities. Which must have satisfying news to anyone wanting to show the airport scheme would not really be environmentally unfriendly. Lazell threw a spanner in the works by finding two rarities — Romer’s Frog and Banded Wolf Snake — among 29 species of reptiles and amphibians. (This small island, just 3 km long and less than 1 km wide, has a greater variety of herps than the whole of Britain.)

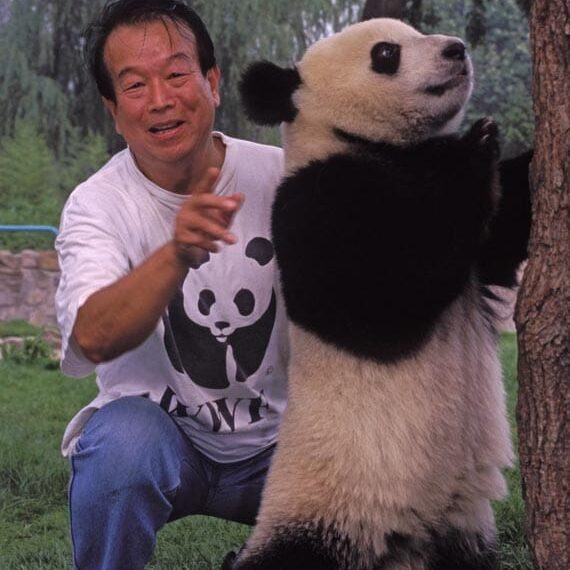

Rare they may be, but Romer’s Frogs hardly rate alongside pandas, tigers and elephants for ability to stir even ordinary folk to calls for conservation. Secretive, nocturnal, cloured a dull brown, the largest of them barely reach 2 cm in length. But while the government remained set on destroying maybe 20 percent of their habitat, the frogs did find a friend in Lau. Supported by the World Wide Fund for Nature Hong Kong and a grant from the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club, he is about to spend two years studying them, to find out where he might release frogs from Chek Lap Kok. First, though, he must find and collect the frogs.

Light from our torches flicking left and right, we walk up the main path between south and north Chek Lap Kok. Behind us is the one place with electric light on this side of the island: the Lin’s place, where the old couple who have lived here over 30 years are making preparations to leave forever. The proprietors of one of Lazell’s convenient beer stops (I bought their last beer this afternoon), their passing will close a chapter in the island’s history. Over 6000 years of human habitation will have ended, and the only people staying will be workmen here to destroy the place.

Sometimes, there are cobras or bamboo snakes on the path. But with the hot summer nights already giving away to cooler autumn, we do not see any snakes; only occasional toads, or painted frogs that secrete a white, noxious fluid when they are caught.

There is an elderly, one room schoolhouse at the top of the slope. With plenty of junk lying around, and some water from a spring, it is a good place to hunt. Best of all, there are Romer’s Frogs. The sharp-eyed Lau finds two young ones — each barely the size of a thumbnail — in a blocked drain, where a pool also holds two Romer’s tadpoles. He carefully places them in plastic bags; they will join the 40-plus Romer’s frogs and froglets he has already collected and transferred to their new, temporary home in his living room.

Until we neared the schoolhouse, the night sounds were buzzing crickets, and the occasional `hoo’ of a collared scops owl. But now, we can also hear the rumble of lorries, drifting up from the north.

Leaving Lau to search the sides of a tiny stream, five of us continue along the trail, towards the destruction. It wends down the side of a valley, and soon we find the valley bottom is filled with a flat expanse of rubble, looking as if it had been washed up by a rising tide. The path continues right up to the tideline, then disappears. There is a house here, and we sit at a table where gas lamps, cooker, mugs and grapefruit skins tell of tea breaks for the demolition gangs. The lorries are nearer now, working maybe 100 metres from us, silhouetted against the dull, maroon glow from a town on mainland Hong Kong. It is 9pm on a Sunday night; the work is set to continue round-the-clock, as two tons of dynamite a day are used to blast away 85 million cubic metres of rock.

Goodyear tries to picture the scene as it was last year. `Glen caught a Banded Wolf Snake down there,’ she says, pointing into the rubble, to a place that was marshland last year. Goodyear’s boyfriend Glen occasionally joins the agency’s surveys as assistant. Mainly interested in mammals, he also enjoys hunting snakes. Last year, he told me of the thrill of catching a deadly banded krait, manouevred carefully using sticks until it was in the bag. `It really gets your adrenalin going,’ he said. `But you’ve got a brick in your pants afterwards.’

Another assistant, Steve Karsen, does not always bother with the catching sticks: he caught a cobra on Chek Lap Kok by grabbing it by the tail as it crossed the path in front of him. Described by Lazell as `a wild reptile collecting machine’, he has a reputation for not changing his t-shirt, worn as religiously as a biker’s new jeans; and Lazell tells how his snake bag holds pork chop bones, cola cans, and the odd venomous snake, `but he has become more civilised since he got married.’

It was Karsen who christened the enormous male pig who lived here. Boinger, Karsen called him, and all who came on the herp hunts stopped off for a look at him, and his legendary male attributes. Now, Boinger’s pen has been buried amongst the debris, as the dynamite and lorries chew away ever more of the island.

We head back to a saner reality, to our base by the ferry pier. While others retire to their tents on the beach, Lau opts to sleep on the path, kept company by his frogs, and I lay my foam mat in a shelter where people once awaited ferries.

I have a fitful night, with too much time spent rearranging mosquito net and blanket, and too little sleeping. Rising at dawn, I find Lau still asleep, and envy those I imagine slept snugly in their tents (they didn’t). A small boat zigzags over the bay, a man steering while a woman beats a tattoo on hollow bamboo, driving fish towards their nets.

Our boat is due to arrive at 9am, and we will not hunt this morning. Lazell walks over, sits on the rocks, and talks with the late-rising Lau about our trip, which has yielded a highly respectable 40 specimens of ten species. He will spend much of today pickling them, and readying them for posting. For Lau, the day will be work as usual, at the World Wide Fund for Nature Hong Kong’s Mai Po Marshes reserve. And the rest of us will spend around three hours wading through water catchment tunnels, to discover what frogs do when frightened (Goodyear has ideas that different species do different things; what we actually find is a fair proportion just vanish).

The boat arrives, and we clamber on board. During the 10-minute crossing to Hong Kong’s largest island, Lantau, we see a few small fish darting clear of the water — sometimes, they leap in shoals, in brief, silver cascades.

`I’ve seen white dolphins a couple of times here,’ says Lazell. He does not know another place this rare dolphin is found — it is yet another species which will suffer from the airport scheme, as the reclaimed land for the runways smothers most of the bay we are travelling over.

Already, there is a tongue of level land behind us, growing seawards as the hills recede. But on our left, Chek Lap Kok looks much as it did last year. By next autumn, it will be gone, leaving only the southernmost hill, and the frogs in Michael Lau’s living room.

Eastern Chek Lap Kok (Hong Kong International Airport to left, at rear), July 1998

[This article appeared in the February 1992 issue of Winds (Japan Airlines inflight).]