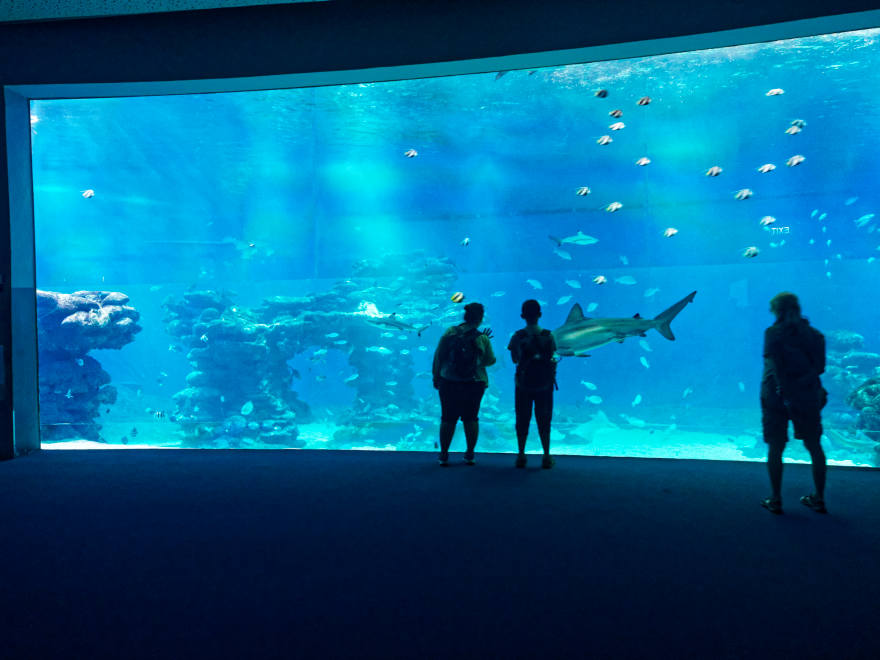

“Look, there are two gazelles,” says my wife, indicating a lush slope with grass and shrubs. Sure enough, I spot one – gazing at us from across a patch of thistles. It’s a slightly built member of the antelope family, with a slender face, upright ears flanking two short horns. Then I notice a second that has slightly longer horns, so is surely a male.

They stroll from behind the thistles to graze on grass and white flowers, affording fine views of their mostly brown fur, slender legs, and the white rumps that help signal danger if they bound away from predators. Given my wife, son and I are in a place called Gazelle Valley, it may seem unsurprising to find gazelles like this, but this reserve is in the suburbs of Jerusalem, surrounded by new apartment blocks.

Mountain gazelles once ranged widely across north Israel and nearby lands, but hunting and habitat destruction led to them becoming globally endangered. This valley was home to their last surviving population in Israel, and in 2015 opened as Israel’s first urban nature reserve. Today, it makes a pleasant place to visit and enjoy the greenery, as a contrast to the crowded, narrow streets of Jerusalem’s Old City; or even the regular city streets with sidewalk cafes that are pleasantly lively on weekdays, eerily quiet during Saturdays, the Jewish sabbath, when no trams or buses run and it seems the people all but vanish.

Around 2km to the north is another place for wildlife in the city – a small bird observatory in the fringes of Sacher Park. It’s a tranquil place, where we sit in a hide overlooking a pool amongst trees, watching warblers, finches and other songbirds that come in to drink and bathe, as well as a kingfisher with white breast and turquoise wings that perches just metres away.

We head east, towards the Dead Sea, taking a taxi as there are few buses, and a driver has offered a good deal. At first this seems a green and pleasant land, with fields and pine woods. But soon, the scenery changes, becoming a rolling landscape of semi-desert, where the yellowish grass blends with the sparse soil. We pass the suburban-style housing of a large settlement – not classed as a town, but a place where Jewish settlers arrived and elbowed out former residents.

The road starts descending, as the land dips. “That’s the sign for sea level,” says the driver, indicating a signboard by parking area on the right, and we continue on down, into the Great Rift Valley – which in simple terms is like a tear in the earth’s crust that extends south through East Africa, to Mozambique.

Soon, we’re heading southwards along the west shore of the Dead Sea, where the water surface is 430 metres below sea level; put the base of IFC, Hong Kong’s second highest building, at the waterline, and its roof would still be around 15 metres underwater. Other than occasional date palm plantations, the land here is rocky desert, almost bereft of vegetation. Cliffs of ochre sandstone tower above us.

At one place, there’s a table mountain standing slightly apart from the main line of cliffs. Here, we ride the world’s lowest cableway – climbing 234 metres, yet arriving at a station that’s still 33 metres below sea level. The hilltop is ringed by cliffs and steep hillsides, and between 37 and 31 BCE the hilltop became the site of a fortress and two palaces established by King Herod the Great. Some three decades after Herod’s reign, Masada was captured by Jewish rebels. This led to a siege by Roman forces, the details of which are lost in time, but ended as the Romans built a ramp on a rocky spur and, according to a historian, this prompted over 900 defenders to commit mass suicide.

Nearby, at Ein Gedi – “Spring of the Young Goat”, we hike up a ravine with a spring-fed stream that tumbles down waterfalls, and is fringed with trees and clusters of papyrus. We see ibex here, looking similar to but stouter than gazelles. Rock hyraxes also seem well used to visiting tourists; although they resemble wombats or giant hamsters, they’re actually related to elephants. During our springtime visit, migrating birds of prey stream overhead; they’re broad-winged buzzards, eagles and kites, and are among millions of birds that pass through Israel each year, en route from African wintering grounds to breeding areas in north Eurasia.

We stay in a hostel favoured by people drawn to the great outdoors, where the receptionists are happy to proffer advice on excursions, and sell us tickets for one of the few buses to pass through the area. This arrives on time, halting by a simple bus shelter just below our hostel, for a two and a half hour journey during which we soon leave the Dead Sea, and travel through the Negev Desert, following a highway across a plain of undulating gravel and sand, bounded by more sandstone cliffs. There are only occasional stops, to drop off or collect passengers at kibbutzim – communal farms that draw water from underground, forming patches of greenery in a landscape that’s otherwise akin to Mars.

The bus arrives at its final destination, Eilat, a resort beside the Gulf of Aqaba in southernmost Israel. This is the prime hotspot for witnessing the huge bird migration skirting the eastern Mediterranean, and I have fond memories of visiting in the early 1980s, enjoying the small town and finding birds in kibbutz fields and date palm groves. Yet more has changed than I realised from reading articles online; imposing mega resorts sprawl along the main beach, and the main birdwatching area is a modest wetland reserve built on a former garbage dump at the edge of town; albeit there are birds, including flamingoes on adjacent saltpans.

Rather than aim for a hotel, we stay in airbnb accommodation, which proves a good choice, with cozy rooms in the home of a local family whose warm welcome is another reminder that there is more to Israel than hard-nosed politics and military might.

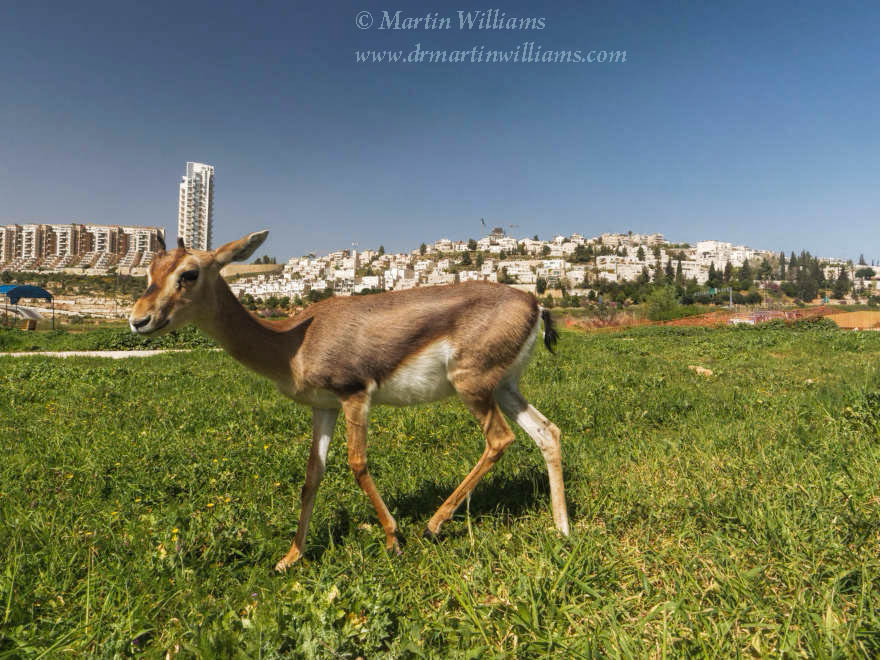

To me, it’s more satisfying to head to nearby hills for some short desert hiking, especially at Red Canyon. This is a slot canyon, a narrow cleft through layers of rust-tinted sandstone, and though carved by rushing torrents during flash floods, it’s mostly bone dry, as when we visit. The hike through the main canyon takes us little more than half an hour, and is eased by a couple of small metal ladders down dry waterfalls. A couple of hundred metres west of and above the canyon, a fence marks the border with Egypt. As we return towards town, our driver suggests I photograph a tank near an army post, yet the crew prove distinctly camera shy – perhaps mindful that in Gaza that morning, a Palestinian farmer was killed by an Israeli tank shell.

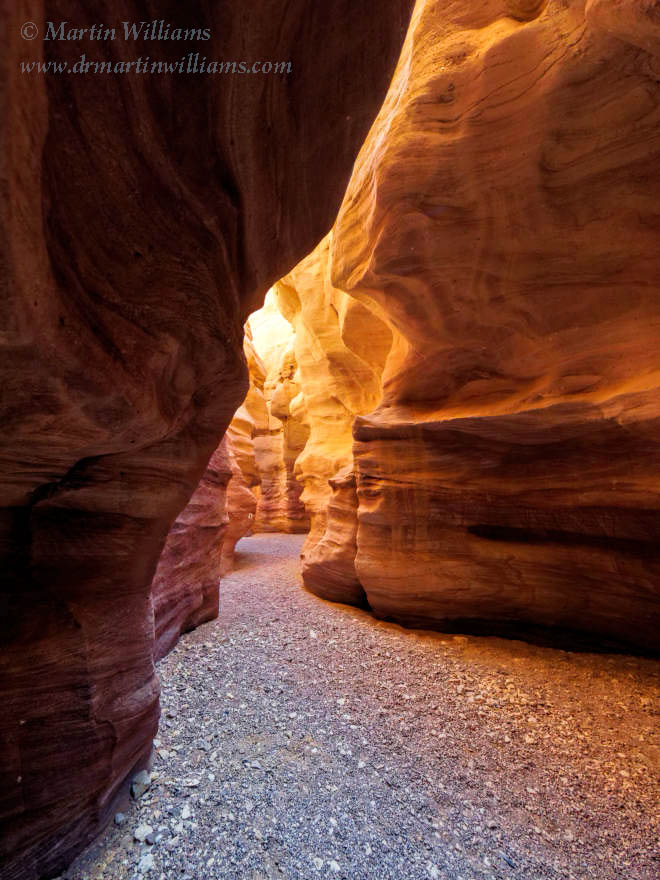

While aware of protests in Gaza beginning, they seem disconnected from us, and in Eilat I focus more on Israel’s treatment of the natural world. To me, it’s striking that while birds barely feature in the town’s tourism promotions, coral fish are a key attraction. They can be admired without even getting wet, at the Underwater Observatory Marine Park. Here, we walk down a spiral staircase to two viewing halls set 12 metres below the water surface, and watch a splendid diversity of fish swimming between corals.

At an adjoining coral reserve, my son and I snorkel in surprisingly chill water. Swimming along a wall of coral, we soon find a difference from Hong Kong marine parks, which permit fishing – as fish are plentiful, and confiding. There’s a school of dark red fish the size of my hand. We also find pale fish marked by black vertical bands, a pair of intense blue butterfly fish with shocking yellow tails.

[Written for the South China Morning Post.]