On the morning of 2 July 2022, as Hong Kong was lashed by gales and rainstorms from Typhoon Chaba, a Government Flying Services helicopter was on a rescue mission close to the eye of the storm. Approaching the vessel that was reportedly in distress, the four-man crew including co-pilot Billy Cheung saw it was aground in shallow waters, with only part of the upper deck, wheelhouse and a tall blue crane visible, and awash with waves from the raging sea.

The crane was listing at a crazy angle, around 45 degrees, and the vessel had broken in two, with the bow section now missing. Looking down at the steeply sloping deck, with three men desperately clinging on to a railing atop the wheelhouse, winchman Cyrus Szeto Chi-pang was reminded of a scene from The Titanic.

Though initial reports had told of 30 people to be rescued, another helicopter had arrived on scene a little earlier, and seen only three men at the wheelhouse, but ran low on fuel while searching, forcing a return to Hong Kong.

The helicopter crew swiftly planned the rescue: Szeto would be winched down, while the helicopter remained above, as stable as possible in the raging winds. While it was lucky the remains of the vessel had grounded, the huge crane mast was a potential hazard if it suddenly shifted; and massive, maybe 10 metre high, waves posed another threat, with surging water pounding the main deck and lower wheelhouse.

In a normal rescue, the winchman might descend from perhaps 20 to 30 feet above ground, but to avoid the mast the helicopter hovered at around 100 feet over the wheelhouse – making the descent akin to dropping from atop a 10-storey building, yet in hurricane force winds, with intense rain squalls set to arrive at any time, and mighty waves below.

Szeto opened the door, ready to descend. He was scared, and thought of his family. But he could also see three men below. “They need me,” he thought. Szeto became calm, intent on saving the men, and started his descent.

Government Flying Service has area of responsibilities across much of South China Sea

The Government Flying Service (GFS) is headquartered at Hong Kong International Airport – where its hangar houses a fleet of two Bombardier Challenger fixed-wing aircraft, a Diamond twin engine fixed-wing aircraft, seven Airbus helicopters and two Eurocopter helicopters.

Mostly, the GFS operates within Hong Kong – with typical flights including mapping surveys, airlifting patients in emergency cases from Cheung Chau to hospitals on Hong Kong Island, along with rescuing hikers in distress.

While saving hikers can be difficult, perhaps requiring helicopter crew to operate alongside cliffs or during night-time downpours, one of GFS’ most notable Hong Kong operations took place in the heart of Kowloon. This was on 20 November 1996, when the 16-storey Garley Building was ablaze in Hong Kong’s worst building fire during peacetime. Manoeuvring in a tight space with higher buildings all around, the crew of a Blackhawk helicopter dropped into the billowing smoke to find four men trapped at a corner of the rooftop, and winch them to safety, even as sheets of flames shot from windows below. (See also Dramatic rescue by brave helicopter crew from roof of blazing Garley Building in Kowloon.)

Nighttime rescue after explosion and fire aboard tanker

The service also has an area of responsibilities spanning much of the South China Sea – where an explosion and fire aboard an oil and chemical tanker resulted in a rescue mission in spring 2022.

It was already dark when the helicopter arrived on scene at 7pm on 17 April, around 300 kilometres east of Hong Kong. With dense low clouds above, no lights on board, the ship was illuminated only by the helicopter’s powerful searchlight. It was pitching and rolling severely on three- to four-metre waves whipped by northeasterly winds.

En route, the rescue crew had learned one man had died in the explosion, leaving six survivors on board. After winchmen Ken Tsang and Peter Li managed to land on the wheelhouse, they found three of the survivors were badly burned, with upper clothing gone, exposing extensive burns with areas of skin missing. “Sit down, so you don’t fall,” Tsang told the first one to be winched, and put a strop round his back. As this touched his burns, the man screamed in agony, but there was no other way to rescue him. For extra support, Tsang added a support below the man’s knees, before watching as he reached the helicopter. The second burns victim screamed too. The third, less severely burnt, was calmer. Li departed as well, and the helicopter headed back to Hong Kong, leaving Tsang on board to await a second helicopter.

Battling bouts of seasickness, Tsang spent about 15 minutes in almost complete darkness, before he and the arriving winchman saved the remaining three crew from the shaking ship. It was almost 3am the next day by the time he arrived home, exhausted.

Operations in tropical cyclones including Typhoon Nesat

Though tropical cyclones affect Hong Kong and the vicinity on only few days per year, they have an outsize impact on GFS operations. When they are approaching, the Challenger planes may fly high over them, and release dropsondes – cylinders roughly the size of your forearm, packed with instruments that transmit data such as position, windspeed and temperature back to the crew, who in turn pass it to the Hong Kong Observatory.

Also while tropical cyclones are over the South China Sea, GFS staff are on heightened alert – knowing there could be calls requiring more than the typical flights, perhaps as vessels encountering problems in rough seas call for help.

The most recent rescue during a tropical storm was on 17 October 2022, as Typhoon Nesat moved from the north Philippines to the South China Sea, and cargo vessel Sheng Li lost power 260 kilometres southeast of Hong Kong. Though the helicopter crew including winchman Alan Lui Ka-ching passed through intense downpours, it wasn’t raining as they reached the stricken vessel. While the stricken vessel was swaying wildly on mighty waves, the visibility was good, and after arriving atop the wheelhouse, Lui was relatively quick to attach two waiting crewmen to the winch line, so they could be lifted to safety.

Seconds later, a huge wave hit the ship, sending a torrent of water over Lui and the remaining five crew. It battered Lui from behind, and he grabbed hold of a rail to keep from being washed overboard, before using one arm to secure himself while swiftly working to complete the mission.

This was the year’s second rescue at sea during a typhoon, after the mission during Typhoon Chaba on 2 July.

Urgent need for rescue during Typhoon Chaba

Billy Cheung arrived at GFS at 7am that day, and half an hour later was in the operations room, helping plan a flight for a crew that had arrived for the 6.30am shift. A report had just come in from the Hong Kong Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre, about a ship that had lost power and was floundering in waves from Typhoon Chaba. It was taking in water, and nine people needed rescuing.

Cheung had dreamed of flying since being a boy growing up in Ma On Shan, playing a flight simulator on his computer and researching aircraft types. After a little actual piloting experience while at university in Australia, he returned to Hong Kong and successfully applied for a position with GFS. “I think it’s meaningful work,” he says. “As an airline pilot, you might fly around the world, but it’s the same again and again. Here, with every mission, you learn something and you’re helping people.”

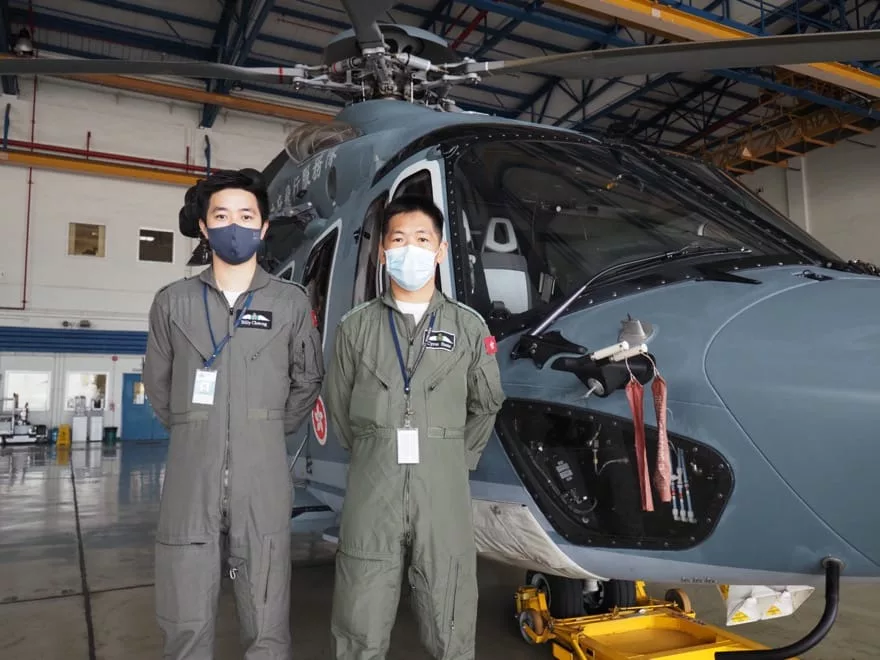

Now 30 years old, Cheung had been with GFS for seven years, during which his only experience in typhoons was with some “routine” local missions. Soon, that would change – as an updated report came in, saying the ship was broken and sinking, and there were 30 people on board. Another helicopter was needed. Cheung was assigned to the crew as co-pilot, along with captain Carl KT Chan, winch operator Clive Chapman, and winchman Szeto.

Szeto previously worked for the Customs and Excise Department, but loved hiking and running, and didn’t want to stay in an office. One day he was running alongside the airport, and passed GFS. His interest piqued, he applied for a job, leading to training as a winchman. Like Cheung, he lacked experience of rescues during typhoons – which are infrequent events, even for seasoned crew.

Again, planning was required before they could depart. There were no obvious places near the rescue site to refuel – especially as oil rigs and airports could be closed during the typhoon. With calculations showing the mission would be around the limit of the helicopter’s range for a return trip, particularly with the need to search and perhaps bring back another nine people, ground crew minimised weight by removing seats from the rear cabin, then moved the helicopter onto the runway. “There was a sense of urgency – the clock was ticking,” Cheung recalls.

It was around 300 kilometres to the rescue site. All the way there, the helicopter was shaking, buffeted by the storm winds. With Chaba nearing the coast of west Guangdong, it was almost as if they were on course to intercept the eye of the storm. “The cloud base was low, and visibility was dropping,” says Cheung. “We tried to keep low, close to the water,” says Cheung. As the sea churned with 10-metre waves, they couldn’t go too low. Then another threat loomed.

“We saw wind turbines ahead,” says Cheung. Pilot KT Chan cursed, and took evasive action by climbing into the cloud.

But with visibility almost nil, the crew were forced to descend again, finding more turbines they had to fly between or just above. As the cloud base was around 1000 feet, and turbines soared to around 800 feet, there was little safety space, even with the blades motionless, turned off to prevent damage in the tempest. The helicopter came into and out of the cloud, and encountered severe rain squalls, with occasional periods of improved visibility affording glimpses of the coast 10 kilometres to 20 kilometres away.

As they arrived above the grounded vessel, conditions had deteriorated even in the short time since the first helicopter had been on scene. They were near the eastern eye wall of Chaba.

Szeto didn’t time his descent, though given standard speeds it must have taken around 20 to 25 seconds. The blue crane was close by, but happily it stayed relatively still, and Szeto reached the wheelhouse roof. Here, he used his legs to help grab hold of a guard rail, which he sat on before turning his attention to the three men. He would have to save them one at a time.

The men looked exhausted, barely able to do more than hold on to the rail. Szeto moved closer to one, within arm’s length. “I’m going to put a rescue strop round you; hold it to your body!” he explained, and pushed the strop over the man’s head. Szeto checked the man was supported by the strop round his back, and was holding fast to a clasp in front of it. Via his radio headset, he told winch operator Clive Chapman they were ready to go.

Face to face, they swung free of the wheelhouse roof, and began ascending. Szeto used a hand to try and keep the man steady, made sure he was still holding on as they swayed in the wind. Looking at the raging seas below, he wondered if the winch cable would support them, and again thought of his wife and daughter, who had no idea where he was right now.

It seemed a long time before they reached the helicopter, where Chapman helped pull the rescued man on board. “Go inside! Go inside!” shouted Szeto, pushing the man into the cabin as best he could. Then, he went down again, making another two trips before all three men were aboard.

The three sobbed with relief. But rather than simply wanting to head for land, they asked if the helicopter team could rescue the other crew members: all 27 had fallen into the sea. With the winching operation having taken almost 15 minutes, Cheung and KT estimated they had only around 15 minutes of fuel left. Even so, they started searching.

All seven men in the helicopter stared at the waves below, hoping against hope they might find someone. “Is there something there?” one of the rescued crew asked at times, but there was nothing other than items of rubbish being tossed around. It was time to return to Hong Kong.

Another GFS helicopter was arriving by then, and a fourth was departing Hong Kong. Two more helicopter flights would also join the search, which continued for a week, with Challenger fixed wing aircraft conducting a total of 14 sorties. Despite their efforts, the GFS teams were unable to locate any of the vessel crew who had fallen into the sea, though there was a later report that a China agency found another survivor.

After arriving in Hong Kong, the three men whom Szeto had winched to safety kept saying “Thank you” to the crew. Unable to speak English with Clive Chapman, they bowed to show appreciation. Then, they were taken to immigration, and for a medical check up.

Reflecting on the rescues his colleagues and him, Szeto says, “It looks quite dangerous, but we’re not heroes; saving people is our work. We aim for four people out on a mission, and four back – and if we have an extra one [rescued], that’s a bonus.”

In August 2006, China’s Vice-Minister of Communications Huang Xianyao visited GFS, to thank helicopter teams for rescuing 91 crew from two mainland China barges during Typhoon Prapiroon early that month. But usually, there are no grand gestures for rescue crew, just thanks from grateful survivors who are last seen departing for immigration.

With friends and family, too, there may be little fuss about missions. “I don’t talk much about work with my wife – I don’t want her to worry,” says Szeto. After arriving home safely following the rescue during Typhoon Chaba, he told her a little about the operation. And as the television news came on, with a report on the mission, his wife proudly told their daughter, “Look – that’s your dad!”

Written for the South China Morning Post Sunday magazine.