Though its setting is unusual – nestled in a forested ravine, deep within Shanxi province, Sheng Shou Temple mainly appears like many temple complexes I’ve visited in China. There are buildings with brick walls, topped with curved, tiled roofs. Doorways lead into six courtyards, with traditional temple style buildings that surely host statues of Buddha and related divine beings; I can’t tell for sure, as on this morning, the doors are closed.

While the temple is well looked after, there are few signs of religious activity. Perhaps a grey-haired woman who walks by is one of the accolytes, attending to nuns or monks who are somewhere out of sight, and putting out fruit that attracts squirrels to outdoor altars.

At the back of the temple, there’s a cliff where a flight of steps leads to a cluster of buildings, arrayed in three tiers so they snugly fit in a rocky recess. The topmost, main building is the size of a log cabin, and has wooden walls on a brick foundation, with timber poles as supports, securely fixed into the cliff face. Painted mostly maroon, with green and gold decorative patterns, these are to me the most attractive and intriguing of the temple buildings.

Judging by photos I find online, they are like a smaller version of the Hanging Temple near Datong, which lies around 400 kilometres to the north, and was likewise built on a cliff, around 1500 years ago. Maybe they are related, and Sheng Shou Temple was originally an offshoot of the Hanging Temple. I can only guess, for while the Hanging Temple is well known, Sheng Shou Temple is akin to a secret place, rating barely a mention even on that wellspring of modern day wisdom, the internet.

Nowadays, as typical of temples in China, Sheng Shou is kept more as a tourist attraction than for religion, yet even by mid-morning there are barely a handful of visitors. One reason may be that the main access is via a path with steep flights of steps down from a car park, 15 minutes’ walk away. But also, it’s tucked away in Qinyuan county, which seems little known even by people in other parts of Shanxi.

Birdwatching race

I’m here through being invited to join a birdwatching “race”, held as part of initiatives to establish Qinyuan as a green county, seeking to move on from reliance on coal mining to also highlight forestry and nature tourism. Along with watching birds, this allows me to explore the county’s cultural and especially natural treasures.

Signposts indicate routes along trails passing the temple, and leading through and climbing the sides of the ravine. They head to destinations like the rather fancifully named Immortals Bridge and Fairy Bridge, a narrow ridge called Dragon Spine, as well as the Third King – a 40-metre pine tree that’s over 700 years old.

From low in the ravine, a side trail winds up a steep hillside to a lookout point atop Linkong Shan. The view is dominated by rolling hills with coniferous plantations; the only buildings in sight are the temple complex, and a small village amidst farmland on the glentle slope above it.

Qinyuan is named for being the origin of the Qin River, a 485-kilometre long tributary of the Yellow River; and one day, Duan Xudong, dean of Qinyuan’s Maternal and Child Care Service Centre and a member of the newly formed local birdwatching society, takes a group of four people including me up to the headwaters, at Qinheyuan. After over an hour’s drive from the county town of Qinyuan, through countryside with green fields and scattered villages, we turn onto a dirt track leading into a steep sided valley. The road twists gently uphill, and the valley becomes like a narrow gorge, before we cross an area of alpine grassland. The riverbed is just dry rubble here, as the land is parched following an uusually dry, warm spell that surely reflects the impacts of climate change.

But just beyond the grassland, we park near a short stretch of stream, with clear water flowing into a pool at the foot of a cliff. This seems mysterious, till Duan shows me water pouring from a vent at the foot of a triangular, craggy hill opposite the cliff.

Above the spring, the riverbed is dry again, and the valley narrows. We walk through deciduous woods with fresh green leaves, hearing the songs of birds like warblers, thrushes and cuckoos that mostly remain unseen. At one point, a male Siberian roe deer appears in a clearing, pauses to stare as I gaze back, then strolls into the trees. Duan is delighted to be here, telling me it’s a beautiful, natural place. And I agree; for with no one else in sight, Qinyuan’s secrets include this trail for hiking while enjoying tranquillity, far from madding crowds.

Pingyao ancient city

I anticipate crowds at the next place I head in Shanxi – Pingyao ancient city. While this is inscribed on the World Heritage List, I know it’s a tourist site, and my experience of a smattering of “ancient cities” in China includes the brash and even bawdy Lijiang in Yunnan province, with commercialism run rampant.

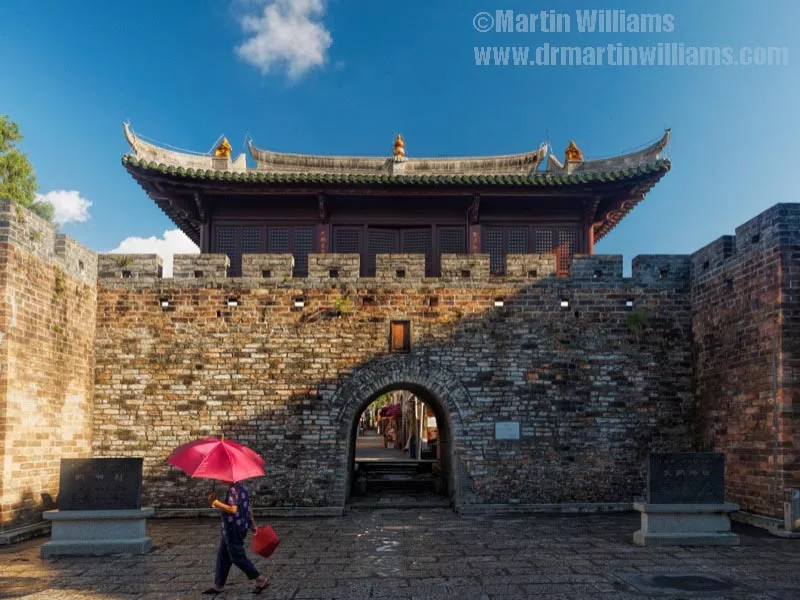

So I’m pleasantly surprised to walk in through a gate in the old city wall, and find narrow, quiet streets within, lined by two-storey buildings hailing from a bygone era. And, with my hotel looking close by on a map, yet over ten minutes’ walk away, I realise Pingyao is on a far larger scale to other ancient cities I know in China. It’s almost square, and around 1.5 kilometres across – big enough to encompass all or most of Hong Kong’s Central business district.

Though first established around 2700 years ago, Pingyao’s main claim to fame is for becoming “China’s Wall Street”. The town served as an important link along the main trade route between Beijing and Xian, with agencies providing armed escorts for cargoes including silver. But some 200 years ago, according to the Financial Times, a merchant devised a system of providing paper “drafts” as guarantees for silver. This led to China’s first bank being established here in 1823, spurring Pingyao’s rise as a commercial centre, which lasted till the banks collapsed along with the Qing dynasty early last century.

Pingyao then became something of a backwater, little changed by either wars or development. A Brown Paper Book of Pingyao relates that in 1986, encouraged by local scholars, in 1986 the State Council declared it was a “famous city of history and culture”; 11 years later, Pingyao gained UNESCO World Heritage status.

Today, there is a resurgence of commercialism, though it’s focused on domestic tourism, with small hotels, restaurants and cafes, plus shops selling Shanxi foodstuffs, handicrafts, toys, and “antiques” of uncertain origin. These commercial premises are chiefly along the four main streets that almost intersect in the middle of Pingyao. Interspersed with them, there are renovated old places like two of the original banks, and traditional homes with courtyards – which are akin to museums that visitors can tour, seeing genuine antiques including furniture, and deep holes that served as bank vaults.

I also check out grand old temples, with colourful statues of wise men and warriors, and stroll along a section of city wall, which abounds with battlements built to withstand marauding armies that never arrived. As a contrast to so much worthy history, I visit a rudimentary waxworks museum, complete with the Avengers, Harry Potter, and Mao Zedong admiring Marilyn Monroe.

There’s a warren of side alleys, too, with fewer stores and hotels, but abundant, densely packed housing. These alleys are less interesting than the main streets, as they’re typically lined with dusty grey walls. Occasional open doorways afford glimpses of courtyards within, to me indicating that even while enthusiastically pursuing business, Pingyao people also sought isolation from the world around them. And eventually, that world changed, moved on, leaving Pingyao as a historical relic.

If you go

Pingyao is easily reached, including by shuttle bus to the ancient city from Taiyuan airport (less than two hours), or by high speed train from Beijing (four hours). There are plentiful accommodation choices, with Qiao’s Family Manson a good choice (I stayed there); these can be found via websites such as www.trip.com.

While entry to the city is free, it is well worth buying a Pingyao combination ticket for 150 yuan – as this allows entry to a host of places including the city wall, temples, renovated buildings. The ticket is valid for three days.