Unearthing China’s Real Dragons

Dong Zhiming, 26, walked atop a low cliff of red and yellow sandstone in China’s Xinjiang autonomous region, his eyes scanning the ground. He was oblivious to the intense summer heat and the desolate, even forbidding landscape of this corner of the region, some 180 miles from the city of Ürümqi. To the young paleontologist it represented rich hunting grounds for one of the world’s rarest treasures — dinosaur bones.

This was his first expedition, and he’d already spotted fossils of prehistoric fish and amphibians, but he had yet to discover any remains of the creatures that most fascinated him. He knew that even experienced field paleontologists could spend months on a dig without uncovering anything significant. Nevertheless, Dong felt strangely confident. He scanned the baked earth for a telltale sign — an unusual mounding of the landscape, an odd protuberance.

Dong and six colleagues from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing had set out from camp after breakfast. A half-hour later they’d halted their truck in the barren stretch he now searched. Then he saw it. Halfway down the slope was a dark, rounded shape like the rim of a buried football.

Looks interesting, Dong thought. Maybe … Carving out steps with his hammer, he climbed down and carefully loosened debris around the object. I was right! he thought. “It’s a big one!” he shouted to an IVPP technician. By late afternoon, they had excavated a vertebra from a sauropod, the most gigantic of dinosaurs, whose members include the Brontosaurus (=Apatosaurus).

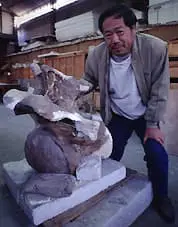

China’s Mr Dinosaur

Since that day in 1963, the man National Geographic Science Editor Rick Gore calls “China’s Mr. Dinosaur” has found countless other fossils. Now head of IVPP dinosaur research, Dong is acclaimed as the world’s most prolific dinosaur hunter. According to Peter Dodson, vice-president of The Dinosaur Society, Dong’s finds include 18 new genera, or groups of species, three more than his closest competitor. His discoveries have shed light on dinosaur evolution and focused attention on China as a preeminent place to study the creatures.

Dong’s fascination with dinosaurs began early. He was born in 1937 in the east coast town of Weihai. His father was a bus controller, his mother a housewife. As a child, he found no outlet for his surging energy in the classroom but loved the outdoors, especially running, swimming and fishing. Then when he was 13, he saw an exhibit about dinosaurs, which the Chinese call konglong — “terrible dragons.” But unlike the dragons of mythology, he learned, dinosaurs were real. On display was a five-foot leg bone of a hadrosaur, a duck-billed plant-eater. It had an electrifying effect on the boy. He began searching out everything he could read about dinosaurs. Over the next decade he learned that China is incredibly rich in fossils; its valleys and flood plains preserved them from erosion, enabling them to weather the ages.

After Dong graduated from university with a biology degree in 1962, he entered the IVPP. Director Yang Zhong-jian, called the father of Chinese vertebrate paleontology, had studied in Munich, then worked in China alongside Western colleagues until 1949, when the Communists came to power and cooperation with the West ended. Now too old to do much fieldwork, he wrote papers, supervised research and taught, hoping for a promising student to carry on his dinosaur work.

Meeting Dong for the first time, Yang asked the alert, strongly built youth, “What do you want to study?” He expected it to be small fossils, which are easily carried and scrutinized in the lab. Dong replied, “Dinosaurs.”

Learning from Yang Zhong-jian

In Yang’s research room, surrounded by books and fossils, Dong learned. By example, Yang taught the spirit of hard work. He wrote about 600 scientific papers, laboriously typing many of them in English. Dong helped his mentor by translating some into Chinese.

“You must love your job,” Yang told Dong. “It won’t make you rich.” Dong did love his work and was good at it. Having seen a fossil once, he could easily identify the species again. He enjoyed fieldwork, too, joining expeditions Yang organized, including the one to Xinjiang.

But times were changing in China. In 1965 the state sent him to Henan province. Like countless intellectuals, he spent a year on a farm, returning to Beijing at the onset of the Cultural Revolution.

By 1966 research at the IVPP had virtually halted. Yang continued to write papers surreptitiously. Dong was sent to a geological survey to advance irrigation schemes in southwest China, where he worked for a decade. He still collected fossils and returned to the IVPP between field trips. On one such visit Dong married Chen Dezhen, who was studying paleoanthropology.

Though in his 70s, Yang still came to his office. He and Dong spent many hours together. Often, Yang looked to the future of paleontology in China. “We must cover the whole country and find new specimens to fill the gaps where material is missing,” he said. He urged Dong to publicize his discoveries to further people’s knowledge about dinosaurs.

Dong took his words to heart. As the fervor of the Cultural Revolution eased, he lobbied the authorities to reinstate the IVPP journal, Vertebrate PalAsiatica, and began corresponding with dinosaur researchers in the West. He soon received offers for cooperative projects.

Sadly, Yang, 83, died in 1979, shortly before Dong made his most important discovery.

A dinosaur graveyard: Dashanpu, Zigong

On a chill December morning in that same year, Dong and a small team investigating sites for a British Museum project in Sichuan province set out for the southwestern margin of a large, fertile basin ringed by mountains. As they drove through the mist at Dashanpu, they heard construction work going on behind a small hill. On impulse, Dong went on foot to investigate. Yang had visited Dashanpu in 1975 after a road-building crew uncovered fragments of bone in the area’s 170-million-year-old rock. “The site is very important,” Yang had told Dong. “It’s Middle Jurassic.” The next year Dong excavated a Middle Jurassic dinosaur in Dashanpu, the first major discovery from that era in China. Few had been found worldwide.

Now, as he rounded the slope, Dong saw that construction work had bared the hilltop. “Let’s take a look here,” he called back to the others. Reaching the top, Dong couldn’t believe his eyes. All around him lay fractured leg bones, ribs and vertebrae. He turned and shouted to his colleagues, “The ground is covered with fossils!” They ran to join him, and stared in amazement.

One, almost dancing with excitement, shouted, “We’ve found a dinosaur graveyard!”

The hilltop had been blasted with dynamite and bulldozers were crushing the already fragmented bones. But stopping the work would not be easy: a state-owned oil and gas company had already invested one million yuan — about $120,000 — in building its vehicle park.

Over the next two weeks, Dong rallied officials and reporters in the nearby city of Zigong. “Middle Jurassic dinosaurs are rare in the world,” he explained again and again. But clearing continued.

Meanwhile, the team dug for dinosaurs. The finds were incredible. Skeletons of more than 100 dinosaurs were eventually collected by Dong’s team and another Chinese team. Most were sauropods — 30-foot Shuno-saurus, stocky Datousaurus and 60-foot Omeisaurus, with a neck half its body length. Sauropod skulls were rare worldwide, but at Dashanpu, five were found. There were squat, massive stegosaurs, sharp-toothed carnivores and two-legged plant eaters barely six feet long, as well as crocodiles, pterodactyls and big fish. There were adult, young and baby dinosaurs.

Dong concluded that the remains of thousands were at the site. As he later explained, “I think there was a large lake, with a big river flowing in. The dinosaurs lived by the river, and a catastrophic flood washed carcasses down to Dashanpu.”

Dashanpu is unique among Middle Jurassic dinosaur sites. A few fossils of similar age have been found in Argentina and Australia. Several localities have older, smaller dinosaurs. But Dashanpu revealed the transformations under way as the creatures surged toward giantism.

In the autumn of 1980 the local government agreed to protect Dashanpu. Later Dong was given official support to build a dinosaur museum modeled on those in the U.S. state of Utah and in Alberta, Canada. Opened in 1987, it has become one of the world’s top three. Displays include the Omeisaurus, 85 percent complete, and some 15,000 square feet of exposed bone beds.

Xinjiang and dynamite

Coupled with China’s “open-door policy,” the finds at Dashanpu enabled Dong to travel overseas and exchange ideas with international colleagues. By 1985 he was helping to organize the $15-million China-Canada Dinosaur Project, one of the largest ever mounted. The fieldwork was carried out over four seasons, putting up to 50 workers in the field at once.

Dong’s co-leaders, Dr. Philip Currie, head of dinosaur research at Canada’s Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, and Dale Russell, paleontologist with the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, had brought their sophisticated excavation equipment, but the Chinese team would show the Canadians a technique they had only heard about.

In the Junggar Basin of Xinjiang autonomous region they found a sauropod rib and vertebra sticking out of a red sandstone cliff. “There must be nearly a hundred tons of overburden,” said one of the Canadians.

“We’ll use dynamite,” said Dong. Unlike the rock in North America, most of which is soft, Jurassic rock in China is very hard; the Chinese were experienced in blasting it.

The Canadians, some of whom worried that dynamiting would damage the fossils, watched as one of Dong’s team blasted rock above the vertebra, then excavated down to the specimen, which turned out to be a new species of Mamenchisaurus, a long-necked sauropod some 85 feet long.

Russell said later that the dynamiting “saved us a lot of time.”

By its end, the Dinosaur Project had identified 11 new species and expanded knowledge of dinosaur dispersal from Asia to North America.

Quirky names and a persuasive manner

Dong’s colleagues admire his uncanny skill at finding fossils. “He’s the best I’ve ever met,” says Russell. “On any day of collecting, Dong will have two or three times as many as anyone else.”

Dong was so busy uncovering fossils during the Dinosaur Project that he even passed up the privilege of naming a new carnosaur he found. Currie and an IVPP scientist named it Sinraptor dongi, in Dong’s honor.

Dong enjoys giving new discoveries quirky names, such as Gasosaurus constructus, a carnivore found at the gas and oil company construction site in Dashanpu.

Tougher to decode is Tianchiasaurus nedegoapeferima. “We found it near Tianchi,” says Dong. “The other part of the name has letters from the names of the stars of Jurassic Park,” in honor of Steven Spielberg’s $25,000 donation to the IVPP.

Despite the fun of naming dinosaurs and the adventure, Dong is quick to dispel any romantic notions of paleontology. “The fieldwork can be difficult,” he says. He often must work hard to persuade local officials to part with their finds. Luckily, he has a knack for it.

In Yunnan, one farmer lay on top of his “dragon bones,” which he believed brought him good luck. Dong squatted beside the farmer and explained that it wasn’t a dragon but a big animal that lived long ago.

“China is one of the best countries for them,” he told the old man. Dong explained how studying dinosaurs adds to our understanding of the world. Finally, the farmer got to his feet, saying, “Okay, you can take it.”

Honored member of the dinosaur people

Today, Dong is an honored member of the “dinosaur people” — 30 or so scientists worldwide who study dinosaurs full-time — albeit one who belongs to the old school. As Yang taught him, Dong looks for specimens to fill in the gaps in evolution, and shows little interest in newfangled theories of his science, though he does work with theoreticians to ensure that his papers are sound.

Some of his ideas are controversial. Scientists have long classed dinosaurs by hip design into a plant-eating group, including the sauropods, and the meat-eating carnosaurs. But in the 1980s, Dong found an oddball dinosaur with head and teeth like a sauropod but feet like a carnosaur. He says it should be in a third order, the segnosaurs, though this notion has found little support among his colleagues.

An idea that finds more favor is Dong’s belief that a descendent of a primitive dinosaur, the dog-sized Archaeoceratops, crossed a land bridge to North America. There, it spawned such imposing creatures as the three-horned Triceratops.

Dong still does fieldwork for up to six months a year. Even in Beijing, his life centers on dinosaurs. “In the office, he thinks about dinosaurs,” says wife Chen. “At home, he reads about dinosaurs. In my ears, there are always the fossils.”

Despite Chen’s gentle complaint, she proudly mentions her husband’s sharp mind, his ability to form relationships with sometimes-uncooperative officials, his from-the-heart manner of dealing with people, and the fact that international experts like Currie and Russell treat him like a friend.

Dong’s dedication sometimes has been hard on his family. In the 1970s, when both Chen and Dong were busy with their careers, their daughter and son lived with their grandparents. Now, their children grown, Dong and Chen live simply in an apartment in the IVPP complex, where they have adjacent offices. Though not wealthy, Chen says they are spiritually rich.

Dreaming of a tyrannosaur

Wearing a rumpled jacket, sweater, jeans and scuffed shoes, Dong sits in front of his computer, working on a paper. Next to the monitor are a nest of dinosaur eggs and an Archaeoceratops skull. Shelves and tables hold bone fragments and a Protoceratops’s lower jaw. On the sofa is a sauropod tail club.

He’s interrupted by a phone call. Philip Currie is hoping Dong can get official permission for a National Geographic photographer to accompany him to a dinosaur egg site. Dong also has to check on the work of five IVPP paleontologists and organize an expedition to the Gobi Desert with Mongolian and Japanese paleontologists.

On the latter project, Dong will seek — and get — funding from overseas, an important aspect of his organizing skills. Given the IVPP’s low budgets, costly excavation of large specimens would be impossible without such help.

Dong appears on television, publishes popular articles and speaks to school children, always hoping there is a budding dinosaur fan in the audience. “If it’s one in a hundred thousand, it would be okay,” he says.

But most often he thinks about hunting dinosaurs. He needs to find another segnosaur to buttress his third-order theory, and he dreams of unearthing a whole skeleton of Asia’s largest carnivore, a tyrannosaur. Then he’ll think about retiring.

[This article first appeared in the January 1997 edition of Asian Reader’s Digest. Reader’s Digest holds copyright in the text.]

Top People

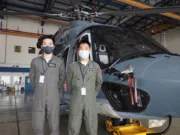

Helicopter crews brave mighty winds and waves to rescue seamen during South China Sea typhoons

On the morning of 2 July 2022, as Hong Kong was lashed by gales and rainstorms…

James Reynolds typhoonhunter and volcano videographer

James Reynolds is a pioneer of travelling to film typhoons, and has added volcanoes to his…

Maasai safari guide Jackson Looseyia

Kenyan born Maasai safari guide, one of the presenters of the BBC’s Big Cat Live series.

A Man for All Sequences Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger made pivotal contributions to studying the chemistry of life, primarily by finding how molecules…

Blue light at last wins Nobel for LED titans

Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura received a Nobel Prize for seminal roles in the…

Genius of the Jungles: Alfred Russel Wallace

Though best known as co-discover of evolution, Wallace was an astonishing man: an explorer, self-taught naturalist,…

The butterfly and the remarkable Professor Hofstadter

Hofstadter’s butterfly, a remarkable spectrum of electron energy levels, was first described in 1976 by Douglas…

James Hansen Godfather of Climate Change retires yet will be very busy

Instead of aiming for a leisurely life after work, Hansen plans to better focus his time…

Pan Wenshi: Scientist Who Fights for the Pandas

When Pan learned how close giant pandas were to extinction, he knew he had to help…

Jill Robinson helping bears

First Jill Robinson was shocked, then she set out to stop the suffering The Great Bear…

Jessie Yu – Hong Kong Single Parents Assoc founder

The best way to get ahead, says this tireless Hong Kong philanthropist, is to help yourself.…

Keeper of the Kings: Captive breeding Philippine Eagles

Domingo Tadena: Captive breeding Philippine eagles

Dr Yang Lihe helping former leprosy patients

Yang knew only too well that the suffering of leprosy patients doesn’t end when the disease…

Dramatic rescue by brave helicopter crew from roof of blazing Garley Building in Kowloon

A helicopter crew rescues people from the roof of a burning building in Kowloon.

Mountain Dog and rebuilding schools in China

Retired Hong Kong schoolmaster helped get many kids from poor families in China back into the…

Mother Ko’s fight for justice

The more lawmakers ignored her, the more determined she became to seek justice

mnice1

Ever since childhood, I did have special affinity towards dinosaurs. At the early stages of my childhood I used to fear them, I still remember crying while watching Jurassic Park in the cinema hall. Later on it became a fascination.