November 1982 [while I was studying for a PhD at Cambridge University]. I had been considering arranging an expedition to study bird migration, perhaps in South America or Asia. The two undergraduates – John Archer and Andrew Stoddart – who were interested in the expedition both expressed an interest in visiting Asia.

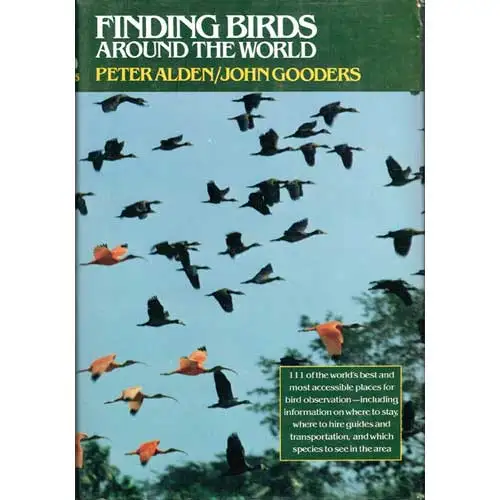

Among the lists of birds recorded at outstanding birdwatching localities around the world (Gooders & Alden, 1981) was a checklist of birds in the Beijing area, based on material which was almost fifty years old. Many of the species on this list were migrants: one of the sources used for the checklist (Wilder & Hubbard, 1924) indicated that substantial numbers of birds pass through the area. Hence eastern China appeared to be a promising area for a migration study.

I began making tentative plans for the expedition. Ed Keeble (another Cambridge undergraduate who was a keen birdwatcher) and Alison Keymer (a member of Darwin College [also my college at Cambridge] who held an ‘A’ permit for bird-ringing) joined the ‘team’.

Could be difficult to arrange, with prohibitive results, maybe of no conservation value

Initial plans were for the expedition to survey migration from April to early June, which would cover the peak of migration. Reference to maps of the east coast of China indicated that Shidao, at the tip of the Shandong Peninsula, was well situated for a study of bird migration.

By February 1983 I began to make enquiries about the possibility of the venture. Dr Christopher Perrins, who had led a SCT-China birdwatching tour to northern China in spring 1982, believed that the expedition would be difficult to arrange: few areas on the coast of China are open to foreigners and, even were the project to be arranged jointly with Chinese students, bureaucracy was likely to cause major problems.

Paul Goriup, Project Officer of the International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP), was even more disheartening. In addition to the difficulties mentioned by Dr. Perrins, he believed that the cost was likely to be excessive and that even if the survey was to take place it was very unlikely to produce any results which could be of value to conservation.

Hence I almost abandoned the idea. The Royal Society had supplied me with a few names and addresses which they felt could be of use. Among them was Premier Study China Travel (subsequently renamed Premier SCT-China) and, despite feeling that a travel agent was very unlikely to assist an expedition without being paid substantial sums of money, I wrote to the company to request advice.

A positive reply, and Beidaihe recommended

Roger Balsom, the Operations Manager of SCT- China, replied to my letter (dated 15 May 1983) to inform me that the company had just moved to Cambridge, and suggested that I meet him to discuss the expedition. Roger believed that it was worth proceeding with our plans: China was continuing to ‘open up’ to westerners and several of the SCT-China tours were to recently opened areas. He offered to help to arrange the travel and accommodation for the project and suggested that Jeffery Boswall, who had led a SCT-China birdwatching tour during spring 1983, might be prepared to act as patron. [I knew Jeffery’s name well; he had presented several BBC nature documentaries I had seen, during travels that took him to most countries around the world.]

Jeffery agreed to the role of patron and recommended that we visit Beidaihe – partly because this would involve less problems with bureaucracy but largely because this was the best place for a migration survey since the migration had been studied previously and there was, therefore, a database for comparison of results. [He later told me that he was very glad that this advice proved correct!]

[I found two big papers by Hemmingsen, and Hemmingsen and Guildal; many fabulous records including species that were “dream” birds in the UK. Also Siberian and other cranes, but I thought these were surely rare there now or we’d have heard of them, so planned to visit from around mid-April to early June, to cover the main overall migration.]

Heartily encouraged, including as may record Siberian Cranes

On 30 July I received a letter from Dr. George Archibald, in response to my request for advice and comments on the expedition plans. In it he “heartily encouraged” the expedition, particularly because we could record numbers of Siberian Cranes. He noted that the species was highly endangered and the world population was less than 300 birds.

Hemmingsen’s data (Hemmingsen & Guildal, 1968) indicated that cranes pass Beidaihe in early spring, and the proposed date of commencement of the survey was brought forward to about 10 March, in the hope that we would record passing cranes. By August 1983 there were 11 expedition members (Ron Appleby, John Archer, Dave Bakewell, Geoff Carey, Ed Keeble, Alison Keymer, Simon Stirrup, Andrew Stoddart, Andy Webb, Steve Woolfall and me). A large group, partly because Roger Balsom hoped that China Youth Travel Service would consider giving a discount to a party of ten or more people.

Some dropped out, others joined

During the next year, Ed Keeble, Alison Keymer, Andrew Stoddart and Steve Woolfall dropped out of, and Steve Holloway joined, the expedition and I began to apply for funds. Roger Beecroft, who is an experienced bird ringer, was to later join the trip to replace Alison.

On 15 August 1984, Dave, Simon and I toured much of East Anglia on a sponsored birdwatch. We recorded 132 bird species and raised over £300 towards the cost of the expedition.

Largely because we knew of no precedent for a (relatively) low budget expedition to China, there was always uncertainty over whether the trip was feasible. In October, Steve Holloway, a man rarely given to wild optimism, wrote “It would seem to most people that it (the expedition) isn’t going to take place and I have doubts myself”.

Fortunately, Geoff Carey did not share Steve’s rather gloomy outlook. From October to December he made over 150 grant applications – approximately half of all the applications made for the expedition (of the two members who bad agreed to apply to industry, Andrew Stoddart had dropped out and John Archer had written to “a few firms”). Though there were fewer positive responses to the applications than I felt the expedition merited, it was extremely heartening to receive funds and discounts in support of the trip.

John Archer’s commitment to being best man at a wedding and desire to find temporary employment forced him to drop out of the membership in January. During this month, Roger Balsom heard from the China Travel Service that it had just become possible for tourists to obtain visas on arrival in Beijing (prior to this independent travellers had to obtain visas in Hong Kong). He received a telex from the Travel Service in Hebei, which had agreed to organise the expedition in China, which gave the prices for each member. These averaged out at £26 per day (a discounted rate!): prohibitively expensive.

Roger believed that we should make use of the opportunity to obtain visas on arrival in Beijing and travel independently (since this would minimise costs).

Departure: with no visas, not even guarantee of hotel being open

And so, on 9 March, the four members of the ‘A-team’ (Dave, Geoff, Steve and I) left London on a Pakistan Internal flight bound for Beijing. We joked about the nightmarish possibility of arriving at Beijing airport only to be refused entry and be sent on the first return flight. Or maybe we’d only receive visas for one month and have to return home before the majority of migrants had begun to pass. Or perhaps Beidaihe would be ‘closed’ to us until later in the spring (we had a guidebook which indicated that the town was only open in the summer).

“Do you have visas” asked a soldier at the airport. “This way please”. We reckoned it took about 10 minutes for the visas to be made ready.

Finding accommodation on our first night proved to be rather a “hassle”: the cheap hotel I knew of was full and we felt too tired to travel around Beijing in search of inexpensive accommodation. Fortunately, we were helped by a group of German tourists, who took us on something of a mystery tour (for them as well as us) before a friend of theirs eventually found us rooms in the university.

Beijing birding productive; but warning of “No birds at Beidaihe”

During the next three days we saw some of the sights in and around Beijing. The Summer Palace was superb and – with over 700 ducks of 12 species gathered on the open water or loafing on the ice which still covered much of the lake, and flocks of Pine and Rustic Buntings by the lake shore – was a fine introduction to birding in China.

We also visited two Chinese ornithologists.

Professor Chang Fu-yuen, the Director of the National Bird Banding Centre, told us of the recent developments in bird ringing in China since its inception in spring 1983. He believed that Beidaihe would no longer be a good place for studying bird migration, as much development had occurred in the area since Hemmingsen’s study. [In translator’s words, “The professor says, there are no birds at Beidaihe.”] Sadly, he was unable to help us obtain permission for Roger and Andy to ring birds at Beidaihe, however he would be pleased to assist British bird-ringers who wish to ring birds at one of China’s 50 established ringing stations.

Professor Tan Yao-Kuang, Secretary-General of the Ornithological Society of China, had not heard of any recent studies of birds at Beidaihe. He kindly showed us some of the collection of 60,000 skins at the Institute of Zoology.

To Beidaihe; good birds then “pretty birdless”

On 14 March we took a train to Beidaihe. We arrived in the late evening, and took a taxi to the West Hill Hotel, which was to be “home” for the next 2½ months.

We made our first tour of the town on 15 March. The area was still in the grip of winter; ice covered the tideline, a floe drifted past offshore, the trees were bare, the grass yellowed by the dry cold. Along the seafront few birds were to be found; the occasional Daurian Redstart or Hoopoe in villa gardens; a Long-tailed Rosefinch was an unexpected find (the species had not been previously recorded at Beidaihe). As we walked back towards the hotel, we were elated to see 47 Common and 13 Red-crowned Cranes heading north, low over the fields, the latter appearing ghost white in the grey afternoon light.

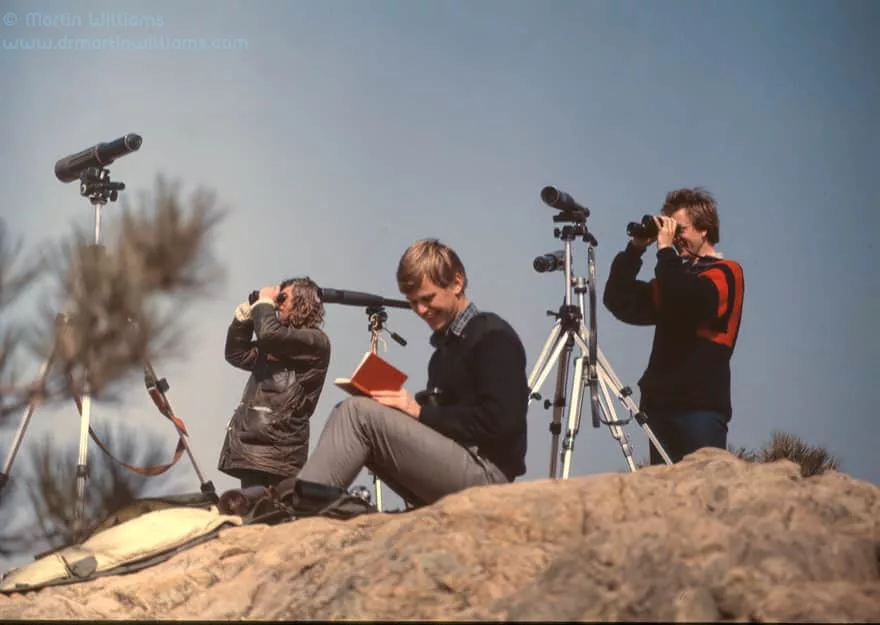

We began counts from the Lotus Hills on 16 March. Few migrants other than Bean Geese passed the watchpoint on this and the next three days, and Steve was moved to remark, “What do you call this, Martin? Pretty birdless I call it.”

On 20 March, a party of three Siberian Cranes were seen from the Lotus Hills watchpoint. I missed, them much to the amusement of Dave, Geoff and Steve. The hotel provided us with a banquet that night, in lieu of our intention to stay for three months. Excellent food, much toasting with Mao Tai (Chinese firewater).

Wave days, including geese and cranes

21 March was a wave day. The morning belonged to the Bean Geese, which passed in flocks of up to 400. They were just lines of dots above the horizon when first picked out through binoculars to the south of us; as they approached we could discern their shape and colour and hear the continuous loud honking calls. From around noon, the cranes were to steal the prize for the best bird spectacle any of us had seen. Three species passed in a succession of flocks between 12h00 and 16h00. As with the geese, they flew in ‘V’ formation; viewed side on we could see wave-like ripples pass down the flocks as birds rose and fell in time with their leaders.

With a background of blue sky or the distant mountains, the Red-crowned Cranes, particularly, were a superb sight, described by Hemmingsen as a beautiful poem.

The day produced totals of 1,016 Bean Geese, 533 unidentified geese, 631 Common, 128 Red-crowned and 122 Siberian Cranes: well worth our early arrival at the town! The following day also proved excellent for crane migration, with totals of 556 Common, 50 Red-crowned and 15 Siberian Cranes and 475 unidentified cranes. Siberian Cranes, particularly, continued to occur over the next three days (the day totals were 135, 178 and 18: the total on 24 March included a flock of 108 birds) and there was another wave of migration on 26 March, when we logged totals of 632 Common, 10 Red-crowned, 169 Siberian and 14 Hooded Cranes and 453 unidentified cranes.

[As the flocks passed over, we took to announcing, “No birds at Beidaihe!”]

Since the bulk of the cranes passed between 12h00 and 15h00 the wave days could produce some amazing birdwatching: from 13h57-14h07 on 26 March, we recorded flocks of seven, 102 and 56 Common, 188 Common with two Hooded, 5 and 58 Siberian and 10 Red-crowned with three Hooded Cranes; eight minutes later 38 Siberian Cranes flew past.

The fourth, and last, major wave of crane migration was on 31 March. The totals recorded were 1,424 Common, 19 Red-crowned, one Siberian and six Hooded Cranes and 562 unidentified cranes. An immature White-tailed Eagle was also noteworthy.

Two hundred and fifty-seven Hooded Cranes (83% of the total recorded during the survey) flew north on 2 April. The day was overcast and there was some rain – conditions which we found inhibited the migrations of the other three species of crane.

On 4 April, there was a vast flock of Bramblings – estimated to number some 33,700 birds, in the fields beside the Tai-Ho [Daihe].

Spring underway in early April and passerines arriving

By early April, spring was underway and our attention began to shift to the passerines which were beginning to arrive in some numbers. Orange-flanked Bush Robins [Red-flanked Bluetails] were to be found flycatching amongst the undergrowth; above them tiny Lemon-rumped Warblers [Pallas’s Warblers] shivered out their songs.

On 8 April, low cloud and mist prevented the count from the Lotus Hills. There was our first influx of passerines, including the first Yellow Wagtails and Stonechats, and at least 170 Black-necked Grebes were on the sea.

Similar conditions prevailed on 9 April. During the morning an excellent movement of ducks and waders passing east over the sea was recorded from Temple Beach. Totals included 377 Spot-billed Ducks, 527 Garganey, 66 Falcated Teal, 10 Mandarin Ducks, 41 Little Ringed Plovers and 92 Kentish Plovers. Ron and Andy arrived at midday. just in time to see two of the Mandarin Ducks and, after briefly watching three or four Orange-flanked Bush Robins around their chalet, be taken on a whistle-stop tour of eastern Beidaihe [on the rather basic, Flying Pigeon and similar, bicycles we were using to get around the area].

There was a wave of grounded migrants, and it seemed that every locality visited produced a “lifer” for one or both of the new boys. Rustic and Yellow-throated Buntings were at West Hill Gully, two Dusky Warblers afforded excellent views along the seafront, a Black-faced Bunting shuffled on the ground near Lighthouse Point, the male Harlequin (first seen on 6 April; it stayed for over four weeks) was still at Fishhook Point, two Dusky Thrushes were among the birds on fields above the point.

Eagle Rock Gully was superb. In the stream, a Grey Wagtail fed. There were six Orange-flanked Bush Robins, three Lemon-rumped Warblers, two Dusky Warblers and a Siberian Accentor. A pair of Long-tailed Rosefinches – a species Andy had especially wanted to see, flew in and afforded excellent views. The male was a beautiful bird: delicately built, agile, washed bright pink-red, silver white on the sides of the head, bright white wing bars. Birds at the reservoir included two Oriental Pratincoles (the first of the spring); two Great Bustards passed north.

Day totals included 75 White Wagtails; 64 Orange-flanked Bush Robins (43 were recorded at West Hill alone), 17 Lemon-rumped Warblers, 117 Yellow-throated Buntings and 250 Grey Starlings.

Raptor passage, as powerful winds arrived

26 April proved to be of interest for raptors. A few Eurasian Honey Buzzards, Pied Harriers and Northern Goshawks were recorded from the Lotus Hills during the morning and early afternoon when the weather was fine and sunny. During the latter half of the afternoon, a dust storm swept in from the west. The sand and dust blown by the near-gale force winds greatly reduced the visibilty. Soon after the leading part of the storm had moved out to sea, the three of us on the Lotus Hills saw the first of a succession of raptors which appeared from the south-east and passed westwards before heading north a little way inland of the Hills. The birds, which had presumably been migrating over the Bay of Bohai before being forced to head for land by the onset of the storm, flew slowly, low over the ground. Thirty-six Eastern Marsh Harriers, 28 Pied Harriers, 11 Northern Goshawks and 13 Common Buzzards were among the birds which passed during this period. The wind died away by evening, and a small party of Pacific Swifts hawked insects over the hills. Among them was a small swift with pale underparts and rump and a fluttery flight; we are still unsure of the identity of this bird which could be new to science (perhaps a swiftlet; probably Himalayan Swiftlet).

In the early hours of 28 April, we were all woken by great peals of thunder from a storm which brought torrential rain and lasted from ca. 02h15-03h15. The storm passed south, over the Bay of Bohai, and the morning was fine and sunny. This was a superb day.

Migrants which had, presumably, encountered the storm over the bay, sought shelter at Beidaihe or headed inland, low to the ground. The coastal trees and bushes, particularly along the dunes between Tai-Ho [Daihe] and Yang-Ho [Yanghe], held superb numbers of grounded migrants. It seemed that every tree held at least one Inornate Warbler, Lemon-rumped Warbler or Dusky Warbler. Flocks of Little Buntings passed low overhead or fed amongst the scrub inland of the dunes. Water and Olive-backed Pipits, Stonechats and Black-faced Buntings were common. Birds such as Red-throated Flycatcher [Taiga Flycatcher], Yellow-breasted Bunting and Yellow-browed Bunting were recorded for the first time.

I had arranged to do a sponsored birdwatch on 1 May, with proceeds going to the expedition. Ninety-one species was the final tally; not bad given the paucity of resident and breeding birds at Beidaihe.

A spell of inclement weather, from the late morning of 2 May (when persistent heavy rain arrived from the west) to 5 May, produced very few birds. Roger and Simon arrived on 3 May, and on 4th Roger made his attempt to buy a stool for use in a hide he was making. He selected a suitable chair, in a café we ate in, and began to explain to the waitresses that he wished to buy it, and how much would it cost, please? (all this with a knowledge of fewer than five words of Chinese). The bemused girls did not seem to have been trained to serve westerners who wanted to buy furniture, and it was eventually left to a boy who emerged from the kitchen to decide on a suitable price (ca. £5), which was duly paid. A cook shortly appeared – a large man, not looking too happy – and placed Roger’s money back on the table. Evidently not company policy, the sale of furniture.

A further wave of visible migration, and more arrivals of migrants

The weather cleared by 6 May, which proved to be the best day for visible migration since the last crane wave on 31 March. One hundred and forty Pied Harriers, 81 Northern Sparrowhawks, 29 Northern Goshawks, 667 Asiatic Golden Plovers, 276 Little Curlews, 1,000-3,500 Barn Swallows and 500-1,200 Red-rumped Swallows were among the birds which passed north over the coastal plain.

On the morning of 7 May, flocks of passerines headed inland over the Lotus Hills. Observers at the watchpoint lagged totals of 29 Richard’s and 158 Olive-backed Pipits, 648 Little and 15 Black-faced Buntings: many more birds must have passed unrecorded. There was a similar movement on 8 May, when the birds noted from the Lotus Hills included 225 Olive-backed Pipits and 451 Little Buntings; 119 Olive-backed Pipits and 241 Penduline Tits were recorded passing northwards over Fishhook Point.

19 May was initially fine and sunny; rain set in by mid-morning and lasted well into the afternoon. From ca. 06h30-09h15, flocks of Curlew Sandpipers arrived from the south, landed briefly at the Yang-Ho [Yanghe] estuary and flew off northwards. A total of 490 birds were recorded passing in this manner. Even before the onset of the rain, there were grounded migrants along the coast and at the reservoir. Damp vegetation harboured Lanceolated Warblers, Black-faced and Chestnut-eared Buntings, open fields held Richard’s Pipits, and there were flocks of Chestnut-flanked White-eyes and Inornate [Yellow-browed] Warblers in the trees. Brown Shrikes, Black-browed Reed, Thick-billed Reed and Radde’s Warblers also occurred in excellent numbers.

Towards dusk it appeared that birds were still arriving from over the sea. Exhausted Radde’s and Inornate Warblers and Chestnut Buntings were on the grass fringing the beach at Legation Point, where a flock of 50 Chestnut- flanked White-eyes and two Black-naped Orioles flew inland.

The fine weather on 20 May enabled a more thorough survey of the area than was possible on 19th, when the rain prevented birdwatching for more than four hours. Though it was apparent that many birds had gone, there were some high counts of migrants recorded, particularly at the reservoir, where totals included 16 Schrenck’s Bitterns, 33 Purple Herons, 26 Baillon’s Crakes, 350 Yellow Wagtails, 59 Brown Shrikes and 34 Lanceolated Warblers.

The numbers of migrants dropped rapidly after this date. Only late migrants, such as Thick-billed Reed and Lanceolated Warblers, occurred in numbers on 27 May, when there was a small “fall” of grounded birds.

To Beijing and Emei Shan, and plans for autumn 1986

The three of us who had remained at Beidaihe since 14 March (Dave, Geoff and I) left the the town on 2 June. We headed south for two weeks, and climbed Emei Shan in Sichuan Province, where we watched the sun rise over the clouds and saw superb scenery, including the distant Himalayas, and birds such as minivets, niltavas and the two species which are endemic to the mountain (Crested Parrotbill and Emei Shan Liocichla).

We then returned to Beijing and visited Professor Tan Yao-kuang at the Institute of Zoology. Here we were kindly allowed to examine skins in the hope that this would assist us with identifying some of the more difficult birds we had seen at Beidaihe. In the event, this proved to be of value for identifying some of the birds seen on Emei Shan, but left us puzzled with regard to certain identification problems at Beidaihe (e.g. whether any of the pipits we had seen may have been Blyth’s Pipits Anthus godlewski; this species closely resembles the Richard’s Pipit).

I met Professor Wei-shu Hsu (Head, Dept. of Zoology, Beijing Natural History Museum). He had recently returned from a visit to Australia, where he had participated in a study of wader migration. He was planning to expand his work to include studies of seabirds, waders and migration, which have, as yet, received rather little attention from Chinese ornithologists. We briefly discussed the possibility of a co-operative project to study migration in China, perhaps at Beidaihe (such a project will take place this autumn [1986]).

We flew back to Britain on 24 June.