Hunting and habitat destruction have brought these magnificent cats perilously close to extinction. Can the most threatened of the sub-species claw its way back?

The scratch marks on the tree high in the mountains of Hunan province, south central China, are barely discernible today: four thin vertical lines a few inches long, slightly wider spaced than the fingers of my outstretched hand, scoured into bark that’s since mostly healed.

Yet these marks are still significant, as they might bear witness to a moment when a magnificent animal signalled its presence to the world, slashing the bark to announce, “This is my land!”

hirteen years ago, a research team including American biologist Gary Koehler found the marks, then fresh, which became a clue suggesting that the South China tiger might have clung to existence in remnants of forest.

Looking at the fading scratches, I imagine the tiger making them as a kind of SOS for himself and his kin: “We’re still here, but we’re in trouble. If you don’t act soon, we’ll be gone forever.”

Did anyone really listen, or has the South China tiger faded from existence? I’m in China to try to discover if this, the most threatened of the five remaining tiger sub-species, might still exist in the wild, and to meet individuals dedicated to saving it. [Update: see note below, re wild South China tiger photographed in the wild in Shaanxi province, October 2007.]

This article first appeared in the Chinese edition of Reader’s Digest. Reader’s Digest holds copyright in the text.

Last Call for the South China Tiger

Like many people, I’ve long been fascinated by tigers. I marvelled at their lithe gait, their orange fur with its tangle of black stripes, their penetrating gaze. “Tiger! Tiger! burning bright/ In the forests of the night,/ What immortal hand or eye/ Could frame thy fearful symmetry?” wrote English poet William Blake in a brilliant summary of the animal’s splendour.

Yet the tiger as a species has proved fragile – all too easily dispatched, its kingdom shattered by mortal hands. As the last century began, three sub-species were snuffed out within decades. In India, surveys indicated the country’s tiger population had plummeted from 40,000 in 1900 to 1,800 in 1970. Today, thanks to the efforts made by the Indian Government, there might be around 3,000-4,000 tigers in India.

At the onset of Project Tiger, a project launched by the Indian Government in 1973 with the aim of saving the nation’s tigers, the outside world barely knew about China and tigers. Yet China is home to four sub-species. They’re tightly woven into Chinese culture, a symbol of strength in traditional paintings and one of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac.

For all the Chinese tiger’s cultural significance, real ones were hunted and trapped, their forests replaced with rice fields as human population swelled. Under Mao Tsetung, over 3,000 tigers were killed as masses of people rushed to eliminate “pests”. A major threat was poaching for tiger bone, used in traditional medicine.

The South China sub-species was reduced to remnants in scattered, mountainous areas that were too difficult to clear. At last, the central government introduced laws protecting it in the late 1970s.

Working with Chinese teams and drawing on his expertise with American carnivores, Gary Koehler conducted a Chinese government and WWF co-sponsored survey in 1990 and 1991. He recorded signs in 12 reserves. Koehler believed that there were few tigers in the wild and the populations sparse and scattered. He warned, “The South China Tiger (Panthera tigris amoyensis) is in immediate danger of becoming extinct.”

The “Father of the South China Tiger”

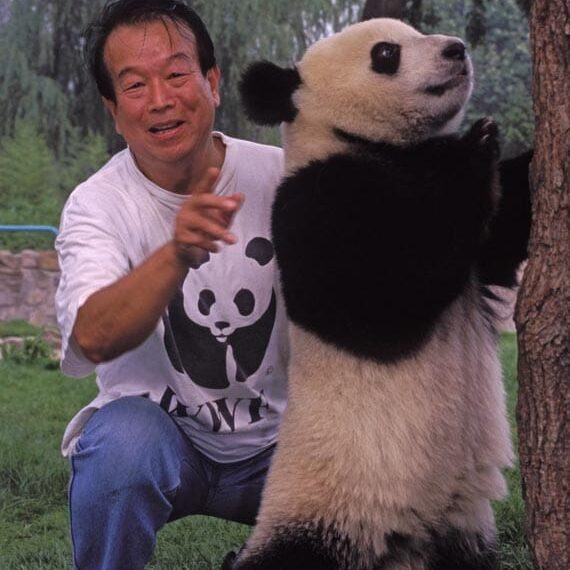

Koehler’s survey encouraged the Chinese government to bolster protection of reserves. Yet there were still much to be done. Indeed, it may have vanished altogether had it not been for one man: Huang Gongqing, a 65-year-old veterinarian whom the Chinese press has dubbed “The Father of the South China Tiger.” Huang, who breeds tigers in captivity aiming to eventually release them into the wild, may represent one of the species’ best hopes.

A graduate of Nanjing Agriculture University, Huang was assigned to the zoo in Suzhou, near Shanghai. in 1961. Appointed director in 1984, he bought pairs of Siberian and South China tigers from other zoos and began breeding them. He soon learned to tell the species apart. South China tigers were taller, with slim waists, long noses, and thinner, more closely spaced stripes.

Huang evolved his own, often unconventional, techniques for treating sick animals, combining veterinary and human medicine. Once, when a tiger could barely walk and stopped eating, he drip-fed it with an IV tube in its leg. The cure worked. He also gave his charges a diet including vitamins and bones to supply calcium.

Thanks to Huang, 77 tigers have been born in Suzhou since 1988, 26 of which have gone to other captive facilities. His work has won support from the Suzhou government, which built a US$1 million tiger breeding facility for him, opened in 1999.

Tiger breeding centre

Other experts often turn to Huang for help and advice. At the beginning of November 2002, I arrange to meet him while he’s visiting the government-funded Meihuashan South China Tiger Breeding and Research Centre in Fujian province in southern China. Huang is advising this centre’s founder, Luo Mingxi, and his team about rearing tigers, which they hope eventually to release into the wild, Meihuashan Reserve.

Slightly built with an infectious smile, Huang is in high spirits when he greets me at Meihuashan. He leads me to a building housing three adult South China tigers and three cross tigers , each with its own room opening into an exercise yard. “Tigers born here have learned to catch and kill live animals like goats,” Huang tells me. This is boosting hopes they can acquire the skills needed for life in the wild.

I spy a pair of tigers, a male and female, in the enclosure. The male watches me like a curious dog. When I walk the track round the enclosure, he and his sister follow, hugging the fence. When I run, they run, enjoying the fun. Suddenly the male jumps at the fence and leans on it with his front paws above my head. He is magnificent. When I thrust a stick through the wiring he grabs it with his teeth and pulls it from me effortlessly. He looks cute, but wields immense power.

Three cubs are born one night while I’m spending five nights at Meihuashan. Huang and Luo Mingxi show me the video of the births recorded by remote camera. As proud as a new father, Luo watches as Huang winds the tape to key moments. “Look, her belly’s moving,” Luo says as the mother-to-be lies on her side, panting. The tiger scratches at her cage floor and Luo scratches at the air in sympathy. “Come out!” he says. At last the first of the cubs emerges.

After we’ve seen the births replayed, Huang flicks a switch and the monitor shows live feed. The mother is sprawled on the floor with two cubs suckling, another playing by her head. “Go on eat,” Luo urges this youngster, which is no bigger than a house cat.

Luo soon plans to build big enclosures on wooded hilltops nearby. In these “finishing schools,” he explains, tigers will learn to hunt prey including deer. Transmitters will be implanted under each animal’s skin so it can be monitored once it is released in a reserve.

The fashionista, the banker, and the tiger charity

Huang and Luo are not the only experts hoping to train young South China tigers for life in the wild. Another – more unlikely – project is just getting underway. Unlikely because it’s happening in Africa and was devised by Quan Li, a 41-year-old Beijing woman whose background is in the fashion industry.

Having studied English literature at Beijing University, then an MBA in business administration in the US, Quan later worked for Gucci and was responsible for its worldwide licensing business. Eventually she resigned and married Stuart Bray, a London-based investment banker. After Quan had visited different game reserves in Southern African countries, she became enamoured with the South African conservation model, which involved eco-tourism supporting local communities. Inspired, she figured Chinese conservation could benefit from a similar approach, along with protecting wild populations and captive breeding. In October 2000, Save China’s Tigers was launched in London, backed with Quan and Stuart’s own money.

Believing the help of South African expertises could prove invaluable , Stuart bought 35,000 hectares of farmland in the Karoo in central South Africa that would be restored as rewilding habitat for South China tigers. Soon after, in May 2002, a Chinese delegation headed to the republic, visiting Stuart’s land and meeting local officials.

Since then, with the blessing of China’s Forestry Administration, Quan has assembled a team to help run the South African project, including a carnivore expert who has rehabilitated lions, cheetahs and wild dogs. In early September, 2003, Cathay Pacific Airlines flew two cubs from Shanghai Zoo – male and female – to South Africa.

[Update, September 2022: news reports have told of an acrimonious divorce between Li and Bray; with much arguing over money in Save China’s Tigers; for instance: Judge Says Ex-Banker Used Trust to Hide Cash From Wife, in which Bray hints at raising money akin to Walter White in Breaking Bad!]

Hupingshan: a last wild refuge for the South China Tiger?

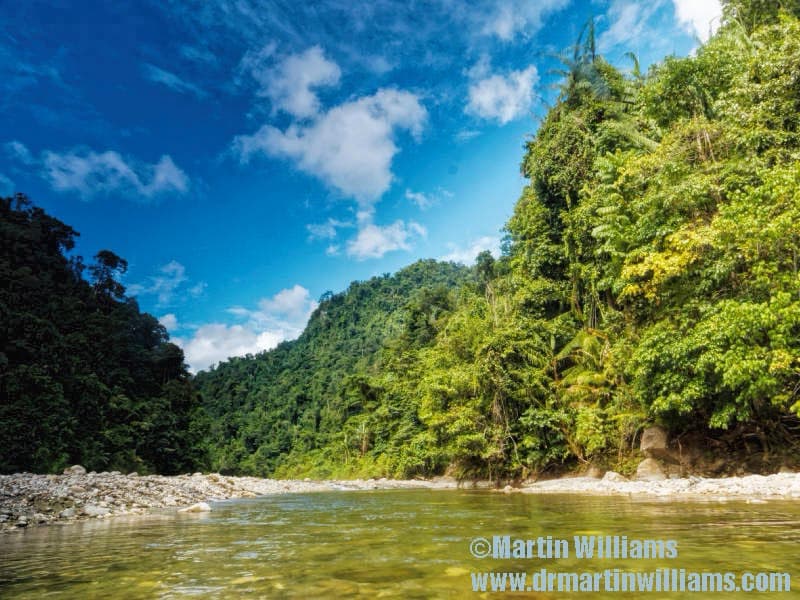

Suppose the Meihuashan and Africa projects do rear tigers ready for release, are there habitats that may even still harbour wild South China tigers? To try to find out, I plan a visit to Hupingshan, a 650-square-kilometre reserve in Hunan province that some wardens say could still be home to the big cats.

Less than two weeks before I’m due there, I receive an email from Quan Li. Ron Tilson, who headed a recent survey in the area funded by Save China’s Tigers, has declared the South China tiger extinct in the wild. He’s quoted as saying, “There are no tigers. There is no prey, and there is no habitat.”

Well, we’ll see.

At Hupingshan, I meet Liao Xiansheng. Originally a forester, Liao began working for the reserve when it was established in 1983. Though he retired in March 2002, he is still searching for evidence of South China tigers, having noted over 100 reports of sightings in regular week-long expeditions.

Liao is encouraged that at the beginning of 2001, a tiger was heard roaring in the reserve by a farmer, then by reserve staff checking the report. It was around the same time I received the email about Tilson declaring the South China tiger extinct.

After a night in a hostel, we rise early. Our small party includes one of the reserve’s three research staff and a three-person television crew. I climb into a jeep, which Liao steers up a rough track into the heart of the reserve.

It’s early winter and drizzle turns to snow as we ascend. At a farmhouse, we stop to ask young farmers to help us carry provisions. There aren’t enough volunteers, so Liao picks up a sack of rice, slings it over his shoulder and sets off through the snow. He is in his 50s, but he’s still a tough mountain man.

Liao leads us on foot through a gully clothed in spindly woodland. He stops at a tree, which has a small metal box fixed to its trunk. Inside is a camera that fires off when an infra-red sensor detects motion. “This is an animal trail,” says Liao. “If an animal passes here, it should be caught on camera.” Liao has 15 cameras in this area. As yet they’ve photographed deer and pigs but no tigers.

We set off again. Snow carpets the ground and all is silent. As the trail drops through forest, we pass the fading scratch marks found during Gary Koehler’s survey. Seeing the sparse cover, it seems to me there can be little food here for tiger prey like deer, and little shelter.

But Liao seems implacable. “A lot of experts have visited and told me the high forest is good for tigers,” he insists.

Next day Liao takes us down to below a thousand metres until we reach a steep valley several kilometres long and clad in dense forest. Liao tells me there are other such valleys in the reserve, and in a neighbouring reserve in Hunan province. Now I can imagine tigers living here unnoticed.

We meet a farmer and his wife walking along a road. I ask, “Have you ever seen tigers?”

“Yes,” says the farmer. “About ten years ago, I saw two at the edge of a stream.”

Leaving Hupingshan, I reflect on what I’ve seen, and feel encouraged. With its plunging mountains guarding pockets of impenetrable forest, Hupingshan could provide habitat. The South China tiger could survive – just – in such mountain retreats [update 2022; no word of them here since, so surely gone].

And there’s another reason tigers may have weathered the worst of the onslaught on their homes. China has begun to protect its forests. With timber industry jobs gone and farming tough, many people have begun to leave the tiger’s last strongholds for cities. Moreover, resurgent vegetation is expanding the areas where tigers and their prey could live. Previously, I’ve seen new forests on formerly cleared slopes in neighbouring Chebaling, a Guangdong province reserve where staff told me of recent sightings.

Still, the South China tiger needs more than a place to live; it’s in dire need of assistance from the species that’s almost snuffed it out. During my travels, I’ve met people committed to saving it, people who inspire others to join them, to establish and fund captive breeding and training schemes. With such help, the tiger might still rip calling cards into trees.

The South China tiger isn’t set to burn bright across large areas. There isn’t room. But we have a chance to rekindle at least a small flame so our world remains home to this king of the South China forests.

It won’t be easy, but failure to try would be as shameful as the tiger is magnificent.

South China tiger article in Chinese (pdf)

Divorce departure and tigers in africa

Sad news in media the past few days, about Li Quan divorcing from Stuart Bray.

Caixin has article mentioning this, also looking at state of save South China tiger project. Includes:

[quote]now the financial backer and operator of Laohu Valley faces money troubles. Quan Li, a former fashion executive for Gucci and founder of Save China’s Tigers, has filed for divorce from her husband, the foundation's financial backer. The divorce is likely to put financial stress on the trust.

It may be time for the tigers to come home, but where in a badly deforested China can they go?

…

The agreement signed in 2002 stipulated a reintroduction of the tigers into the wild in China by 2008. That deadline came and went, but the tigers remain abroad. There is still no confirmed date for their return.

…

Lu Jun, director of the SFA's wildlife research center, said the majority of the tiger's former habitat is regions that have been highly developed.

"Restoring a suitable habitat for the survival of the South China tiger is not something you can do just by talking about it," Lu said. "It's already a much more complicated proposition than originally anticipated, so progress on the project is proceeding much more slowly than originally anticipated."

…

Some at the international conservation union say China might be better off trying to save the four subspecies of tiger that remain in the country. Xie said the Amur tiger – also known as the Siberian – that is native to northeastern China and Siberia is not extinct in the wild. The wild population still had healthy numbers, she said, meaning there is time to build conservation areas on the Sino-Russian border.[/quote]

Project to Save South China Tigers in South Africa Lost in Wilderness

There's also an article, from August, on Save China's Tigers website, saying:

Chinese Tiger Project Going Strong Despite Departure of Co-Founder [ie Li Quan]