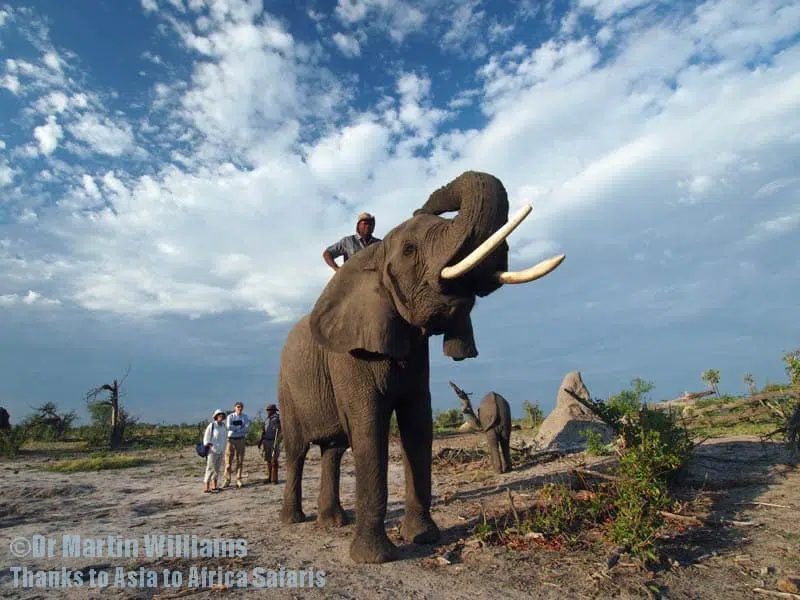

It’s a scintillating morning in north Botswana, and I’m privileged to be standing within touching distance of an African savannah elephant, which seems as big as a Kowloon minibus. There’s just a shrub between us, and she curls her trunk around a cluster of leaves, rips them off and pulls them to her mouth.

This female isn’t wild, but part of a small captive herd, and I’m walking along with her plus another female and a two-year old baby. Two men are riding and guiding the big females, another walks as a guard, with a rifle in the unlikely event a wild animal attacks, while two tourists and I stroll along, like temporary members of the herd.

All herd members have names, and the female close to me is Cathy. She’s the nearest I will ever meet to Nelly the Elephant of the children’s song, who left a circus “and trundled back to the jungle”. After being captured in Uganda at the age of two, she lived in a Canadian safari park until being shipped back to Africa, and participating in elephant back safaris – during which you can ride on or stroll with elephants.

We move on, walking steadily through the bush. At times I stop and take photos, trying to be mindful of advice not to turn my back on the baby lest she decide to “play” with me: weighing over 600 kilos, she could readily knock me down.

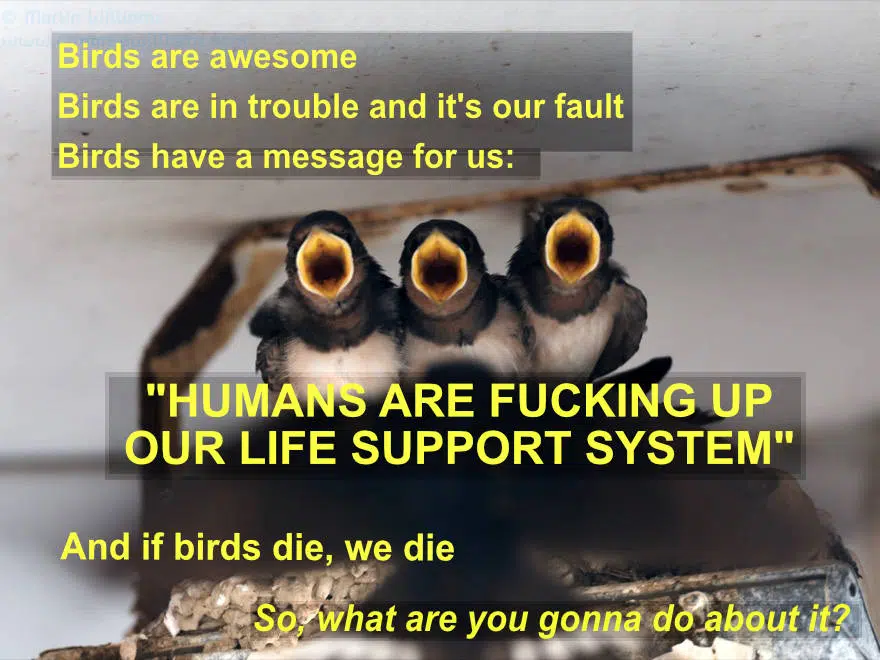

Helping elephants through ecotourism?

I’ve come to Africa after becoming a little involved in efforts to stem the ivory trade, which has recently led to poaching levels soaring. Last year [2013], perhaps 30,000 elephants were killed in Africa, for ivory that was mostly destined for China; and Hong Kong customs seized ivory from at least 1675 individuals. Partly, I want to learn if it’s possible to help by becoming an ecotourist.

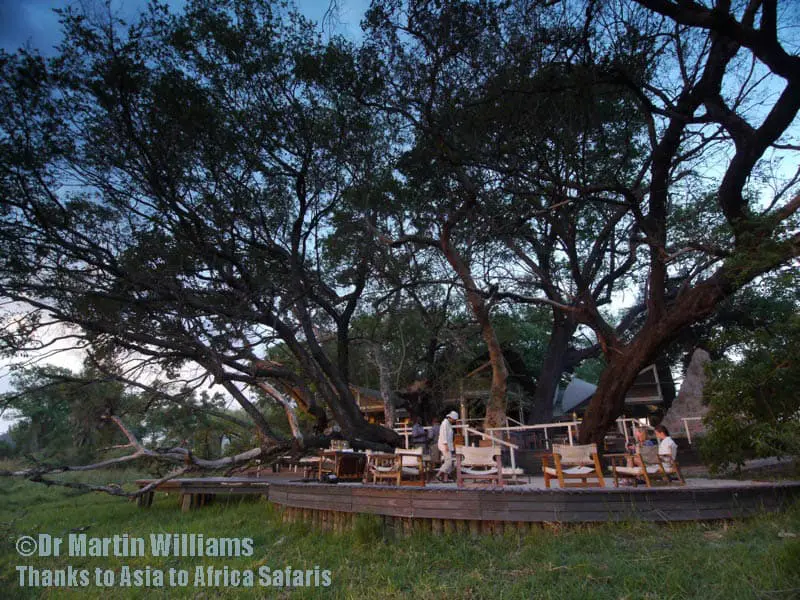

Thanks to an itinerary planned by Asia to Africa Safaris, I’m visiting two safari lodges – Abu Camp in the heart of the Okavango, a 150,000 square kilometre delta within a desert, and King’s Pool, by the Linyanti River on the border between northeast Botswana and Namibia. While Abu Camp is evidently the place for elephant back safaris, both offer regular game drives plus boat trips in search of wild elephants and the multitude of other species sharing their habitat.

Wildlife at lodges and on game drives

I readily see various mammals and birds without even leaving the lodges. Hippos are immersed in pools in front of both, an African fish eagle proclaims territory beside Abu Camp, and at King’s Pool the buffet attracts unwanted guests including a baboon that chases a waiter into the kitchen – causing laughter among those of us watching, and a warthog busily digs a hole beneath my bungalow.

But with just four nights in Botswana, there’s no time to just sit around. This is a dream destination for me, and I want to get out and find wildlife that till now I’ve seen only in zoos or on tv. Thanks to drivers who double as guides with sharp eyes and encyclopaedic knowledge of the fauna and flora, the outings prove astonishingly productive.

We soon find giraffes, with babies around the size of a horse staying close to their two-storey high mothers. There are several species of antelopes, the commonest being impalas, many of which have recently given birth to doe-eyed youngsters, their arrivals timed for the onset of the rainy season. Small herds of zebras graze on areas of fresh grass.

Predators are far scarcer. We pause at a hyena den, where a battle hardened female nurses cubs. A call over the walkie-talkie alerts us to a female leopard, which is relaxing on the ground. On a shaded log above her, a young cub almost dozes on the remains of a young impala, looking content as a house cat sated on cream.

There’s a wonderful variety of birds, too. Lilac-breasted rollers are extravagantly colourful crow relatives that perch on branches and swoop after insects. Waterbirds gather at small pools, ranging in size from plovers to metre-and-a-half tall storks with pied plumage and giant red and black bills. Turkey sized hornbills shuffle along the ground, seeking insects and reptiles.

At one place, I alight from the vehicle to creep close to and take photos at a colony of carmine bee-eaters – intense red and blue birds that are bringing bees and dragonflies to feed youngsters hidden in underground burrows. I keep an eye out for a black mamba that an American family and guide Ndebo Tongwane (“NT”), saw yesterday, but there’s no sign of this venomous snake.

Nor does a buffalo appear and charge me, or a pack of lions emerge to eye me for lunch. There are dangers here, yet nothing like absurd tv shows such as Man vs. Wild might suggest. Indeed, the only lion I see strolls casually past us as we watch from the vehicle, and almost falls asleep close by.

The elephant’s a keystone species – and tourism can help

The wealth of plants and animals here depends partly on the elephant, a “keystone species”. Elephants not only munch leaves, but also knock down trees to ensure there’s still open grassland, and even their dung provides food for termites and other creatures.

Without elephants, the landscape and wildlife would be transformed. And this would in turn impact tourism, second highest revenue earner for Botswana after mining. “The tourism industry has changed my life; it’s made me who I am right now,” NT tells me: born in a farming area, he now supports his extended family through guiding.

Of course, there can be significant downsides to tourism, and I’ve heard of safari ventures where too many vehicles chase after animals, their tracks damaging fragile landscapes, and of expanding accommodation potentially leading to pollution that will harm the sensitive Okavango. Yet tourism seems vital for wildlife conservation here, as it can help counter threats such as expansion of cattle farming that’s accompanied by threats such as overgrazing, disturbance to wildlife, and farmers killing lions and other predators. As evidence of the conflict between wildlife and farming, a bull released from the Abu Camp herd was shot by farmers, along with ten other elephants, at a ranch outside the protected area.

Thanks to low-impact – and high-priced – tourism, the lodge environs I visit remain pristine, and government support and military patrols ensure elephant poaching is not rampant. Wild elephants we encounter during game drives are relatively relaxed as people approach.

One morning, a guide and I come across a herd of around thirty elephants, which are moving in a scattered formation, grazing on low trees. We drive to the front of the herd and stop, to watch them pass.

For a few minutes, we’re in the midst of the herd. Females with calves stroll casually past. An adolescent male pauses to stare at the vehicle, shakes his head, and trots on by. The only sounds are of elephant trunks ripping foliage to eat; they tread so carefully on sensitive feet that we hear no twigs or branches snapping.

Four elephants file through a gap between trees, making up the rear of the herd. Then, they are gone, hidden by the sparse cover, as if they have melted into the bush.

Film I made of 2-night stay at Abu Camp:

And film of 2-night stay at King’s Pool: