Chairman Mao Was Here

The Kennedys put Martha’s Vineyard on the holiday map, George Bush gave Kennebunkport its 15 minutes of fame, very late British prime minister Harold Wilson will be forever associated with vacationing in the Scillies, Mikhail Gorbachev — though he might prefer it were otherwise — is indelibly linked with Foros on the Black Sea coast. And summer retreats by the upper echelons of the Communist Party have helped make Beidaihe, some 280 km east of Beijing, China’s highest-profile seaside resort.

Which is not to say Beidaihe is a household word in the west. (Can you even say it?) It might be visited by three to five million people each summer, and known throughout the world’s third largest and most populous country, but outside China, Beidaihe rates few mentions other than when the leadership is in town.

Even then, there is no media coverage of leaders hobnobbing with locals or rubbing shoulders with the masses on teeming beaches. Reports are based on snippets of information emerging from the party’s hotel, where policies are debated in villas set amongst wooded slopes above the seacoast and, should the need arise, a road leads into low granite hills, to a nuclear shelter with heavy duty drive-in door. Sometimes, photos emerge too: these once showed Deng Xiaoping taking a dip at the hotel’s private stretch of beach, though by last summer he was reportedly content to while away his days playing bridge, and this year ill health prevented his sorjourn by the sea. Prime minister Li Peng has also frolicked in the sea for a photo opportunity, to disprove rumours he was in poor health after a heart attack.

Out beyond the leadership compound’s walls, gates and sentry posts, Beidaihe is an odd mix of genteel resort with echoes of European seaside towns in a bygone era, and brash playground for the masses, with spanking new hotels, restaurants, trinket shops, karaoke bars and fun palaces that have sprung up as the town has boomed since Deng unleashed China’s economic reforms. Yet, while outwardly transformed, at its heart Beidaihe remains a small, rural town. (So how do you pronounce Beidaihe? `Bay die huh’ is close, if you don’t fuss over tones.)

Beidaihe and Bird Migration Flyways

I have been visiting Beidaihe for a little over a decade. Not for the beaches and fun palaces, but to watch birds. Lying near a confluence of flyways — which are like seasonal rivers of birds linking northeast Asia with south China, Indo-China, Australia and even east Africa — Beidaihe is one of the world’s finest migration watchpoints, and I have spent thousands of hours scanning skies from hilltops, and hunting through the town’s woods, gardens, gullies, fields, estuaries and marshes. I have known quiet days when the migration seemed becalmed by stable weather, days with birds in fair numbers, and occasional, outstanding `wave’ days.

There were wave days when the migration surged along the coast and flocks of cranes headed by one after another, often far from the hilltop vantage, sometimes passing right overhead in interlocking chevrons of grey cranes mixed with stunning, white Siberian and red-crowned cranes, sky writing patterns like fantastic Chinese characters as the air rang with their haunting, bugling cries. Or buzzards, sparrowhawks and delicately buoyant pied harriers gathered in thermals of rising air, circled upwards, then glided on down the wind.

And there were wave days when migrants halted — forced down by wind and rain or awaiting autumn cold fronts that would sweep them on southwards — and warblers and buntings abounded in coastal trees and shrubs and there was a good sprinking of scarcer birds like the yellow-rumped flycatchers that seem to glow amongst the foliage.

Beidaihe resurgence

There were no flycatchers when I first arrived at Beidaihe. It was mid-March 1985, and spring was barely underway. Chunks of sea ice littered the tideline, knee deep in places. There was more ice in starkly wooded gullies. The fields were bare, the streets almost deserted. Locals wore padded coats and fur-lined hats with ear flaps that were sometimes left to stick out comically sideways (we nicknamed them `Deputy Dog hats’). The hotel receptionist was surprised when four westerners pitched up and announced they wanted to stay, staggered when they said they wanted to stay for three months. (`Three months? Ah yes, three days.’ … `Three weeks?’ … `Wait a moment please,’ as he went to fetch the manager.)

Our main goal in arriving so early in spring was to watch for cranes. A Danish scientist, Axel Hemmingsen, had seen large numbers of cranes when he studied birds at Beidaihe in the 1940s, but no one had monitored them since. After days that seemed fine to us but clearly did not suit the pernickety birds, we witnessed our first, magical crane wave. More waves followed, then, as the crane numbers tailed off, other birds joined the migration.

Beidaihe emerged from its winter dormancy. With longer, warmer days and the onset of spring rains, the woods and gardens were transformed by fresh greenery. Seafood restaurants and shops made ready for the summer. Ice lolly sellers emerged from their hideaways and began touting for trade. Tourists trickled in; a few swam, although the sea was still cool, others strolled along the promenade and beaches. Seeing men in cheap suits and shiny shoes going down to the water’s edge with boys topped with flat hats or girls in Sunday best frocks, I was reminded of photos from English resort towns around four decades ago: perhaps, for the working classes, the novelty of a seaside holiday was much the same.

Beidaihe was also emerging from another, longer period of dormancy. The granite headland on which the town sits had been visited by several emperors — the unifier of China, Qin Shi Huangdi [221-210 BC], had a palace above the eastern beaches during the third century BC. But the resort had its origins in 1893, when a British engineer who was helping build a nearby railway line decided that, with its low hills, beaches and sea breezes, the headland was an ideal place for escaping the interior’s summer heat. On his recommendation, the first vacationers arrived. They evidently pronounced the engineer correct, as Beidaihe, until then a poor fishing village, quickly became popular with China-based diplomats, merchants and missionaries, and wealthier Chinese.

In 1898 the Qing government formally declared Beidaihe a summer resort. To accommodate the `foreign invaders, Chinese warlords and politicians’ — as the New China News Agency reportedly once dubbed them — villas with balconies and pavilions overlooking the sea were built amongst pines and cypresses. Beidaihe was further transformed by the addition of a dance hall, a bar, a cinema and tennis courts. Austrians founded Kiesling and Bader’s, a bakery with attached restaurant that survives today as simply Kiesling’s. By the 1940s, Beidaihe could boast 700 villas and hotels, and had played host to visitors from at least 64 countries.

Under Japanese occupation from around 1938 to 1945, Beidaihe the resort surely ground to a halt. And following the Communist Party’s rise to power in 1949, visits by foreigners were rare; the masses — for whom even goldfish rearing became `evil’ — were yet to arrive. Even so, Mao headed to Beidaihe. In 1954, on a rocky outcrop just minutes’ walk from the site of the Qin emperor’s palace, he wrote a poem asking where fishing boats had gone during a storm. Mao also instigated the leadership’s summer visits to Beidaihe.

Beidaihe’s resurgence began after Deng took control of China in 1978. Slow at first, the town’s metamorphosis gathered pace as the economic reforms took off. Fields to the east gave way to hotels, sanatoria, and vacation villas owned by companies and state-run industries. A shopping centre with souvenirs and dried seafood sprouted by the fruit market. Karaoke reached Beidaihe, notably at the Twinkle Star Night City, where other attractions include massage by young girls (I tried it once, and was thumped, pummelled, and walked all over — the girl then asked for a tip!) and a swanky night club (far more fun). To the south, a new town appeared, its main highway lined by giant `palaces’ with themes including the Monkey King story and tourist sites around the world.

Further south still, another county tried its luck with another new resort — its special attraction is a big sand dune you can take a chairlift up, then whoosh down on a toboggan.

Summer Season at Beidaihe; and Autumn

I have witnessed the summer season in full swing only once, when I arrived to lead a follow-up to the spring migration survey in August 1986. The town thronged with people. Crowds milled along the main streets and the promenade. While there was space on roped-off, private beaches, several of them restricted to guests of adjacent hotels, the public beach was packed. On the sand near the promenade were arrays of beach umbrellas to guard against peasant-like tanning, as well as changing booths and swimming gear for hire. Heading to the sea in outsize trunks and frilly one-piece costumes, beach-goers bounced over waves on airbeds and inner tubes, or just splashed in the cooling water. At beaches and other scenic spots, photographers advertised their services with photos showing happy holidaymakers, some of them appearing to float between land and sky, others with outstretched hand supporting the rising sun. Ice lolly sellers took up strategic positions on busy corners, or trawled the promenade on bicycles with wooden panniers in which were flasks keeping the ices cool.

In the evenings, restaurants resounded with diners feasting on north China staples and seafood specialities such as fresh local crabs, and the shouts of youths challenging each other in boisterous drinking contests.

As September began, the season was suddenly over. The crowds thinned, days cooled, and a storm churned and chilled the sea.

Beidaihe the small town re-emerged. With business slacker, staff of shops and restaurants stood in doorways, chatting with friends or just watching the world go by. The ropes and guard nets of private beaches were put away. Fishermen laid out their nets on the sand, checking for and repairing holes. Around the town, apples were picked, and rice and maize harvested, the maize cobs stacked on rooftops to dry.

By mid-October, autumn reds and browns tinted the woods of the Lotus Hills park, which at dawn attracted joggers and exponents of tai chi and qigong — one man ran by at sunrise, every few paces twirling his arms and expelling a loud `Hooh!’. The season was advanced by cold fronts that raced down from Siberia, bringing blasts of cold air that tugged leaves from trees and penetrated all but the thickest layers of clothing. By the end of the migration survey, on 20 November, ice covered a small reservoir, and a sandy estuary was frosted white.

Shanhaiguan and the Great Wall

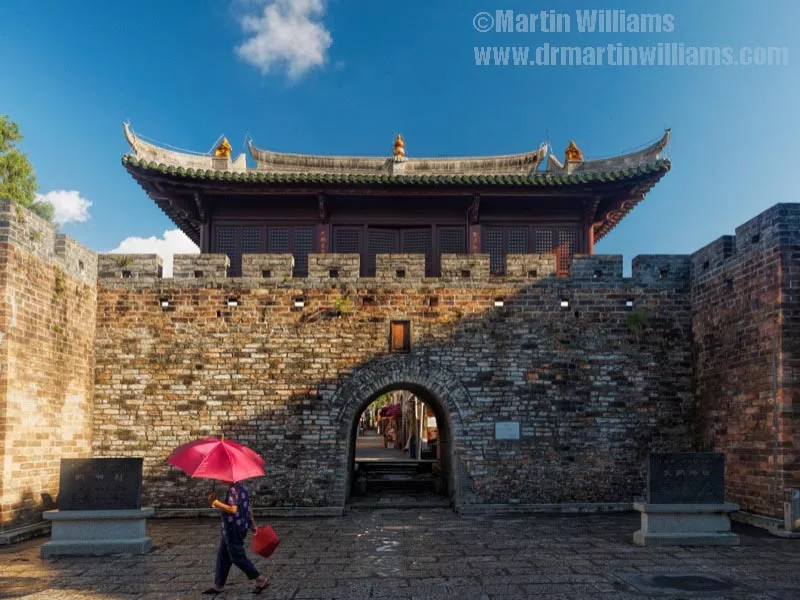

Beidaihe sits on a coastal plain between mountains and sea. To the north, at a point where the plain narrows, is an old fortress town, Shanhaiguan, with sturdy houses and crisscrossing narrow lanes set within four walls. Midway along the northern wall is an arched gateway, with a watchtower perched on top.

Beidaihe sits on a coastal plain between mountains and sea. To the north, at a point where the plain narrows, is an old fortress town, Shanhaiguan, with sturdy houses and crisscrossing narrow lanes set within four walls. Midway along the northern wall is an arched gateway, with a watchtower perched on top.

On the watchtower, bold calligraphy proclaims this to be the `First Pass Under Heaven’ — it is the first pass in the Great Wall, which starts (or, if you like, finishes) at the sea just east of town, flanks Shanhaiguan as it crosses the plain, then makes its first ascent into the mountains.

The watchtower and stretch of Great Wall beside Shanhaiguan have been restored, to attract tourists who, if they wish, can pose for photos in imperial style costumes.

The restorers have laboured on the wall ascending the hillside as well. I visited in 1985, and found little remained of the lower stretches of wall — maybe bricks had been taken for house building — and there was no one but an elderly man whose job seemed to be to tell visitors they were not permitted to smoke, pick flowers, or take away pieces of wall.

Now, the Great Wall on the hillside is again a grand edifice. There is even a chairlift, leading part way to a newly built temple for tourists and to a hilltop looking east over the plain, west across rough-hewn mountains, and north to an almost sheer rock face where the `wall’ is a skeletal, metre-wide sliver of grey, weathered bricks. Another stretch of Great Wall, crumbling but still prominent, and dotted with watchtowers, is a landmark on the journey north from Beidaihe to Old Peak. At 1424 metres, Old Peak is the highest mountain near Beidaihe, and offers a great contrast to the town. The only hostel has no electricity, and water from a well (the local policeman rates it far better for health than any bottled water), but boasts a recently upgraded restaurant — where, unless you eat early, candlelit dinners are the norm [though a new hotel was being completed in autumn 1997]. Rising above the hostel are towering crags. Footpaths and the rocky road wind through the woods and valleys, which in spring are alive with the songs of cuckoos, thrushes and warblers, some of them rare worldwide.

Another stretch of Great Wall, crumbling but still prominent, and dotted with watchtowers, is a landmark on the journey north from Beidaihe to Old Peak. At 1424 metres, Old Peak is the highest mountain near Beidaihe, and offers a great contrast to the town. The only hostel has no electricity, and water from a well (the local policeman rates it far better for health than any bottled water), but boasts a recently upgraded restaurant — where, unless you eat early, candlelit dinners are the norm [though a new hotel was being completed in autumn 1997]. Rising above the hostel are towering crags. Footpaths and the rocky road wind through the woods and valleys, which in spring are alive with the songs of cuckoos, thrushes and warblers, some of them rare worldwide.

Perched on a steep hillside is a weathered chunk of granite like a giant finger, pointing into space. From the base of the finger, there is a view down through a ravine, and out across low, distant ridges with still more stretches of Great Wall, to the plain below — and Beidaihe. It seems a world away.

[This article first appeared in the autumn 1995 issue of Mandarin Oriental.]

Origin of Beidaihe seaside resort

Here's link to an interesting article (pdf file) on the origins of Beidaihe Haibin: Beidaihe the seaside resort. Traced back to an enthusiastic newspaper article published in 1899:

http://www.birdforum.net/attachment.php?attachmentid=306361&d=1296536899