Checking the schedule for long-distance, high speed rail routes from Hong Kong’s West Kowloon terminus, it appears one of the few convenient stops for a weekend away with my wife and son is Huizhounan – Huizhou South.

Huizhou is the name of both a city and the surrounding county in the eastern “Greater Bay Area”, with a mix of urban areas, culture and scenery. Online information reveals the city is noted for gangsters, with Wikitravel reporting, “Huizhou is where the triad crime bosses come to dialogue and chill.”

An hour and ten minutes after leaving Kowloon, the train pulls into Huizhounan. While this looked close to Huizhou city on a map, we take a bus, and the ride into the city takes a little over an hour (only later do I measure, and find it’s over 35 kilometres away as the crow flies).

West Lake and Lingnan style architecture

Huizhou’s top tourist attraction is the West Lake, and we’ve booked into an inexpensive boutique hotel by the northwest shore. It turns out this is in a rather sleepy neighbourhood with buildings only rising to around four storeys high, some hosting chic looking cafes and hostels, along with restaurants mainly serving Cantonese fare.

Rows of broadleaf trees flank a lakeside path, where families and couple stroll past, elderly men play cards at a couple of tables. While slightly disappointed not to see mean-looking tattooed guys in mirrored sunglasses, I’m hardly surprised that triad bosses aren’t chilling by the lake.

China has 36 “West Lakes”, I learn from the Truly Enjoy Guangdong website, but only three are really famous: in Hangzhou, Yingzhou, and here. According to Wikipedia, Huizhou’s lake was enlarged around 1066, along with the addition of pavilions and bridges. Its name derives from a poem written in 1094, comparing it with the Hangzhou’s long renowned West Lake.

From the 1950s to 1980s, housing projects encroached on the lake. But in 2007, the local government began a major rehabilitation project, protecting the remaining West Lake and several historic buildings, and constructing a host of footpaths, bridges, pavilions and corridors in Lingnan – traditional Cantonese – style.

Now, these paths allow for fine strolling alongside the lake. There’s a host of straight, zigzag and arched footbridges interconnecting islets, which are like stepping stones we follow between the west and east shores of the lake. Especially in the east, the paths skirt alongside low wooded slopes, and while downtown Huizhou is little more than a kilometre away, its high-rises are mostly hidden from view, and the landscape recalls the days of long vanished imperial China.

Information boards are dotted around, and make frequent mention of poet, statesman and gastronome Su Dongpo (= Su Shi), who was exiled here in the late 11th century after his writings caused upset in the court of Song Dynasty Emperor Shenzong. There are statues featuring Su, reflecting the scribe’s penchant for lychees and fair maidens.

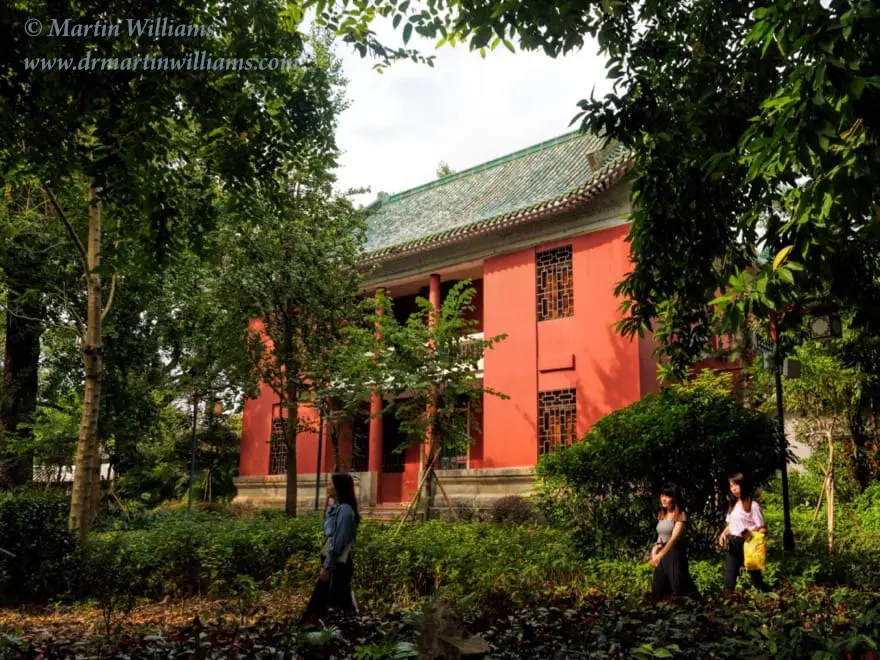

In places, we come across older buildings, like the imposing, two-storey Sunglow Shed, which has intense red walls topped by a sweeping, green-tiled roof. While dating from 1935, this is on the site of the original Sunglow Shed, which was built in 1530 and named after a poem waxing lyrical about, “Scenery on all four sides covered in sunglow”.

The oldest structure here – and in all Huizhou city – is the forty-metre tall, seven storey Sizhou Pagoda, which was built in 1618 atop an island. This is also the lake’s most prominent man-made landmark, and is especially eye-catching when illuminated at night.

Immediately north of West Lake, the main city area of Huizhou is set within a sharp bend in the East River (Dongjiang), which is here over 500 metres wide. With its jumble of buildings including office blocks, it doesn’t look too appealing, but we explore the city fringes along the near bank of the river.

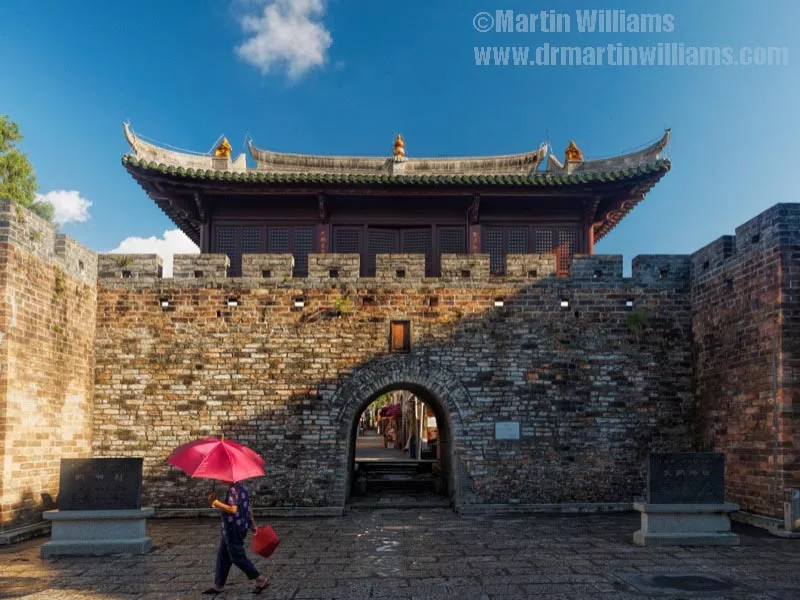

Here there are remnants of old Huizhou – like a row of almost shanty style market stalls packed with fruit, vegetables and other provisions, alongside modern apartment buildings, and a pedestrian only shopping street where neighbouring fashion stores compete over which can pump out the loudest dance music. And that’s quite enough urban tourism for this trip.

Ascent of Gaobang Shan and lake circuit by bicyle

We ride a taxi 2.3 kilometres from the hotel, to the main peak in the area, Gaobang Shan. This is surely little more than 200 metres high, and we enjoy a pleasant walk uphill, along a road where we pass hundreds of families out for a stroll.

At the top, the imposing Guabang Pavilion is modelled on ancient Chinese architecture, yet has a lift to the fourth floor – where a balcony affords panoramic views across West Lake to the city, and down to nearer Honghuahu: Red Flower Lake.

There’s a path with some steep flights of steps to the edge of this lake, which is really a reservoir amidst low hills. Here, we hire bicycles, and follow an anti-clockwise route around the lake, along a road that almost hugs the contours, twisting in and out of a myriad small bays. It’s a fun ride, taking around an hour to make an 18-kilometre circuit.

Then, it’s time to head back to Hong Kong, this time riding a bus – which takes three hours including the border crossing, from Huizhou direct to Kowloon Tong.