I first visited Beidaihe, a resort on China’s east coast, in spring 1985, and have returned each year since, mostly as leader or co-leader of migration surveys and birding tours, a couple of times for a holiday. In all, I have spent over a year at the town, garnering a Beidaihe list with over 300 Asian migrants, and experiencing superb spells of birding. In addition, trying to stimulate conservation work — it was partly on my urging that, in spring 1990, the town established an unimpressive nature reserve.

- Beidaihe Megaticks, and Migration Corridor

- Early spring crane waves at Beidaihe

- Spring songbirds on the China coast

- Qilihai and Happy Island

- Beidaihe Migrants Suffering Declines

- Beidaihe Breeding Birds and Old Peak

- Early Autumn Migration at Beidaihe

- September Songbird and Raptor Flights

- Cold Fronts Driving Beidaihe Autumn Migration

- Oriental Storks, and the Grand Finale of the Beidaihe Birding Year

Unimpressive without landscaping work, that is. I remember waxing lyrical about the reserve’s potential to Dr George Archibald, Director of the International Crane Foundation. Given the numbers of birds traveling the flyway over Beidaihe, I said, the reserve could host bird densities as high as the best migrant traps in North America. “Yes,” replied Archibald. “But these are megaticks.”

[This article originally appeared in Birding (American Birding Association): October 1994 and February 1995.]

Beidaihe Megaticks, and Migration Corridor

Megaticks such as Oriental White Stork (Ciconia boyciana), which is virtually restricted to eastern Russia and China; most of the world population of perhaps 3000 migrates over Beidaihe in autumn. Megaticks like three endangered cranes that are unique to the Far East — Red-crowned (Grus japonensis), Hooded (G. monacha) and White-naped (G. vipio) — as well as Siberian Crane (G. leucogeranus), which hangs by a thread in Iran, yet numbers close to 3000 in the Far East, and passes Beidaihe in the hundreds. And Saunders’s Gull (Larus saundersi), world population perhaps 2000, Relict Gull (L. relictus) (4000-5000), and Nordmann’s Greenshank (Tringa guttifer) (1000), which have all graced the small estuaries at the town — Relict Gull is regularly seen on migration only at Beidaihe.

Then, too, there are the species that have megatick status for many birders, even though they are not rare and endangered worldwide: the species which, in Britain, I knew as `Sibes’. Listed as vagrants in many field guides, the Sibes have always held a certain mystique, as wayward strays from far-off, hard-to-visit lands. Even when they make landfall, they seemingly favor the farthest-flung localities, such as Britain’s Shetland Isles, and, in North America, those remote chunks of rock known as Attu and Saint Lawrence islands.

Beidaihe now ranks as the place to see east Asian migrants. Pick any of the Asian vagrants to North America and, chances are, it occurs at Beidaihe. Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum)? Siberian Blue Robin (Erithacus cyane)? Siberian Rubythroat (E. calliope)? Eyebrowed Thrush (Turdus obscurus)? Lanceolated Warbler (Locustella lanceolata)? All are common. Pacific Swifts (Fork-tailed Swifts; Apus pacificus) pass over in thousands. The estuaries are visited by flocks of Siberian Sandplovers (Anarhynchus mongolus). Wood Sandpipers (Tringa glareola) and Long-toed Stints (Calidris subminuta) prefer damp paddyfields, which in late spring are the places to search for Pechora Pipits (Anthus gustavi).

Beidaihe now ranks as the place to see east Asian migrants. Pick any of the Asian vagrants to North America and, chances are, it occurs at Beidaihe. Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum)? Siberian Blue Robin (Erithacus cyane)? Siberian Rubythroat (E. calliope)? Eyebrowed Thrush (Turdus obscurus)? Lanceolated Warbler (Locustella lanceolata)? All are common. Pacific Swifts (Fork-tailed Swifts; Apus pacificus) pass over in thousands. The estuaries are visited by flocks of Siberian Sandplovers (Anarhynchus mongolus). Wood Sandpipers (Tringa glareola) and Long-toed Stints (Calidris subminuta) prefer damp paddyfields, which in late spring are the places to search for Pechora Pipits (Anthus gustavi).

The town [from the Yanghe north to Qinhuangdao] checklist currently runs to over 390 species; over 300 of these may be seen in a year, only perhaps 14 occurring year-round — the rest are at least partial migrants. The diversity stems chiefly from Beidaihe’s location (map). Lying 280 kilometres east of Beijing, Beidaihe is on the edge of the Bay of Bohai, the northernmost extent of the East China Sea. Several flyways converge in the area, linking winter haunts in southern China, Australia, Thailand and even — for Amur Falcon, Common Cuckoo and Common Swift — south-east Africa, and breeding grounds ranging from north-east China to arctic Russia.

Also important is the variety of habitats. Though the resort has mushroomed since my first visit, the estuaries remain, along with wooded hills and gullies, coastal plantations, and two areas of freshwater marsh. All lie on or near a roughly triangular headland that protrudes from an otherwise smooth coastline, and is itself eroded into smaller headlands — magnets for songbirds and other migrants traveling over the sea. The Beidaihe triangle is largely fashioned from granite, which also forms the low (153m) Lotus Hills, the main vantage for watching visible migration.

Birds overflying the area chiefly follow the coastline, or the narrow plain between the bay and mountains to the west. Leading from Beidaihe to the south of what was once called Manchuria, this plain apparently serves as a migration corridor — especially for birds of grassland and wetland, such as geese, bustards, and cranes.

Early spring crane waves at Beidaihe

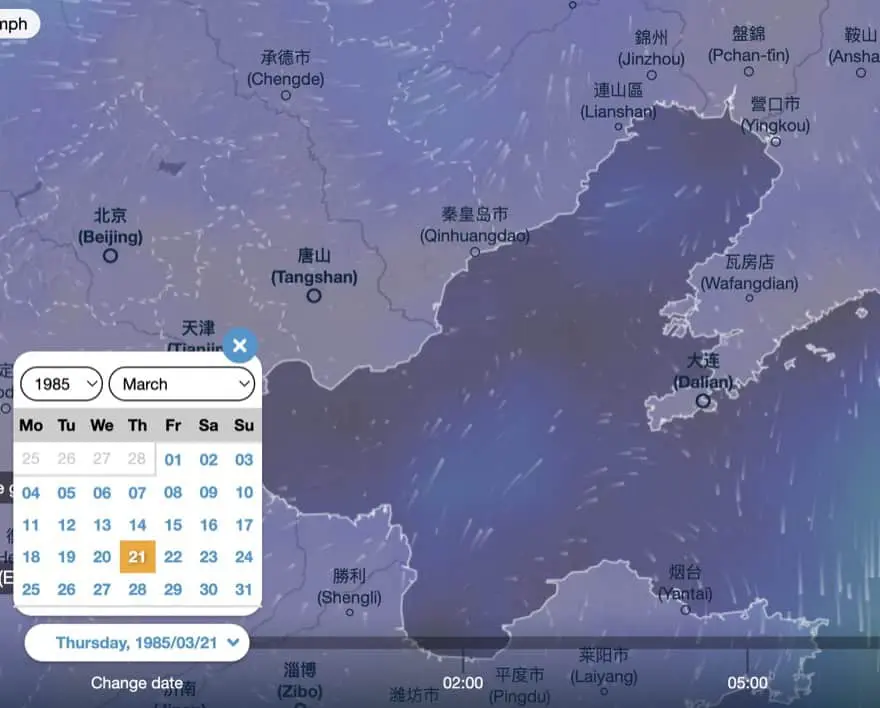

Picture this. You have arrived at Beidaihe in the middle of March. Spring has barely begun: there is sea ice along the tideline, the deciduous trees are bare, grass is yellowed from the dry cold. It is forty years since the last migration survey at the town, by Danish scientist Axel Hemmingsen. You have read his results, which are covered in two superbly detailed papers in an obscure Scandinavian journal, and suggest that the spring survey you are beginning will produce some spectacular birding. Yet much has changed in those forty years — China’s population has more than doubled, and its environment has deteriorated, with wetlands drained, forests felled, and hunting pressures much increased. And the director of the country’s bird-banding center, whom you met in Beijing, has told you, `There are no birds at Beidaihe.’

This was the situation in which the four of us in the advance party of the 1985 survey team found ourselves. We had arrived early in the spring on the advice of George Archibald, who encouraged us to watch for Siberian and other cranes, which are in the vanguard of the migration. On our first day, our early arrival seemed well worthwhile — we saw 47 Common Grus grus and 13 Red-crowned cranes, as well as wintering songbirds such as Siberian Accentors Prunella montanella, and newly arrived Eurasian Hoopoes Upupa epops and Daurian Redstarts Phoenicurus auroreus.

This was the situation in which the four of us in the advance party of the 1985 survey team found ourselves. We had arrived early in the spring on the advice of George Archibald, who encouraged us to watch for Siberian and other cranes, which are in the vanguard of the migration. On our first day, our early arrival seemed well worthwhile — we saw 47 Common Grus grus and 13 Red-crowned cranes, as well as wintering songbirds such as Siberian Accentors Prunella montanella, and newly arrived Eurasian Hoopoes Upupa epops and Daurian Redstarts Phoenicurus auroreus.

Then, we began to wonder. Hours and days slipped by on the Lotus Hills as we watched the skies for migrants, but saw little except occasional flocks of Bean Geese Anser fabalis and Common Cranes. `What do you call this, Martin? Pretty birdless I call it,’ one of our team muttered during a long afternoon watch. The weather seemed okay, with skies often clear and winds light. Maybe the populations had crashed, and the big flights of geese and cranes were history?

But we had reckoned without the cranes’ choosiness regarding the weather. Probably because the coastal corridor has little except stony river mouths in the way of wetlands, the cranes travel over Beidaihe in numbers only on days when the weather is to their liking — a strategy that helps them make the journey of at least 200 km between a wide plain and its muddy estuaries south of Beidaihe, and the marshes in Manchuria to the north.

The weather change that brought our first wave was not startling: the sky remained clear and the light wind swung to the southwest, as a high pressure system moved away to the east. Yet the effect on the birds was dramatic.

The morning of our first `wave’ day, 21 March, belonged to Bean Geese, which passed in flocks of up to 400. Just lines of dots when we first picked them out through binoculars, they approached and passed close to our watchpoint, honking loudly. As the goose numbers tailed off, cranes began passing. Starting around noon, they stole the show.

The weather was mild, almost shirtsleeves, as we watched a succession of crane flocks head north. Like the geese, they were lines of dots at a distance; those flocks that were well inland appeared as little more than lines even when level with us, lines that rippled as birds rose and fell in time with their leaders. Other flocks came close, some passing right overhead. We watched them through telescopes, then binoculars, then through telephoto lenses as we photographed the birds, and marveled at the sights and sounds.

The larger flocks — of 100 or more — were made up of chevrons that interlocked and shifted as the birds traveled on, sky writing ever-changing patterns. Most flocks were of grey birds: Common Cranes. Some were mixed and grey and white, as Common and Siberian cranes flew together. Other, often smaller, flocks were of white cranes: slim, gleaming Siberians, their wings ink-dipped black, and stately Red-crowneds with dark secondaries and black necks. The sky rang with the calls of the cranes — the bugling of Commons and Red-crowneds, the higher, almost mechanical cries of Siberians.

The pulse of cranes lasted around three hours; the late afternoon was quiet. Probably, the birds we saw had left stopover points to the south of us when thermals had developed mid-morning, and aimed to reach at least the south Manchurian marshes before nightfall.

The day produced tallies of 1016 Bean Geese, 533 unidentified geese, and 631 Common, 128 Red-crowned, and 122 Siberian cranes. More crane `waves’, as Hemmingsen had called them, followed. Again, they coincided with high pressure systems slipping away to the east, producing reasonably stable conditions, winds roughly in the direction of the birds’ flight, and a near-guarantee of decent weather at the destination. (Only the peak count of Hooded Cranes differed; 257 flew north on an overcast day with southwest winds, and light rain in the afternoon.)

We finished the spring with totals of 4409 Common, 244 Red-crowned, 309 Hooded, and 652 Siberian Cranes, as well as 1785 unidentified cranes that were surely mostly Commons. Hardly earth-shattering if you consider the half million or so Sandhills that halt at the Platte River in Nebraska each spring, but then Red-crowned, Hooded, and Siberian can barely muster 12,000 birds in all — the 652 Siberian Cranes represented some 40 percent of the world population known at the time.

By the time the crane migration was over, we had coined an in-joke. Watching, say, a chevron of Siberians passing over the town, we would gleefully announce to one another, `No birds at Beidaihe!’

Of course, the cranes weren’t the only birds we saw during the early spring; as their waves came and went, the overall migration was building. Many winter visitors departed during the last two weeks of March; Siberian Accentors, which were common on our arrival, became scarce, the flocks of Eurasian Skylarks Alauda arvensis in the fields dwindled, as did the numbers of Common Goldeneyes Bucephala clangula on the sea. We watched other early migrants pass north: packs of Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus, Rooks Corvus frugilegus and Daurian Jackdaws Corvus dauuricus in tens and hundreds, ponderous Great Bustards Otis tarda in loose parties, a single, hulking White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla. As the numbers of the early birds tailed off, more species joined the migration.

On 9 April, low cloud and mist prevented us from watching from the Lotus Hills. But we did see migration in progress. From a beach hut, we watched ducks flying north offshore: 527 Garganey Anas querquedula, 66 Falcated Teal Anas falcata, 377 Spot-billed Ducks Anas poecilorhyncha, and 10 Mandarin Ducks Aix galericulata. Close relatives of Wood Ducks Aix sponsa, Mandarins were familiar to us as feral birds in England; but now we had seen them truly wild, en route to the riverine forests of Manchuria and eastern Russia.

Spring songbirds on the China coast

During the watch, we noticed songbirds arriving from over the sea. With only occasional duck flocks by midday, we had the chance to bicycle in search of them during the afternoon, and we found there was an influx — a fallout. Red-flanked Bluetails Tarsiger cyanurus were plentiful; their wheet calls could be heard from most of the gardens and thickets. Flycatching low in the still-bare vegetation, they were easily seen, allowing us to enjoy the handsome, blue-and-white males, splashed orange on their flanks. Tiny Pallas’s Leaf-Warblers preferred bushes and trees, sometimes hovering to snatch insects, sometimes shivering out a burst of melodic song.

There were also buntings: a late Rustic Emberiza rustica, flocks of Yellow-throated E. elegans, their crests raised when excited. A pair of Long-tailed Rosefinches Uragus sibiricus lingered at Eagle Gully — they were lightly built, acrobatic birds, the male delicate pink with two white wing-bars.

Another lingering bird was an immature male Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus, on the sea off the rocky east coast. I had found it three days earlier, an unexpected and thrilling sight — the first for Beidaihe, and one of few recorded in China (there have been two more sightings at Beidaihe), as well as a long-wanted life bird.

Less of a surprise were some species that turned up for the first time on 9 April, and would soon become common. A couple of Dusky Warblers Phylloscopus fuscatus were tired and approachable in sea-front bushes, a Black-faced Bunting Emberiza spodocephala shuffled over a patch of bare ground, there were two Dusky Thrushes Turdus naumanni eunomus in a field that is now covered by hotels, and, in the evening, two Oriental Pratincoles hawked insects over the small reservoir.

The spring migration peaks around the middle of May. With a handful of early migrants still to be found, a wide variety of birds that pass primarily at this time, and each day likely to produce new species as the migration gathers pace, two weeks’ birding may yield 200 species.

Among the month’s highlights are some stunning songbirds. Male Siberian Blue Robins are electric blue above, clean white below; fond of thickets, they hop on the ground, tac tac tacking, and furiously vibrating their tails. Also skulking are male Siberian Rubythroats, which put all their plumage in their throats.

Although Blue Robins and Rubythroats might give only brief, tantalising glimpses, Yellow-rumped Flycatchers Ficedula zanthopygia are show-offs. Below they glow yellow, like Prothonotary Warblers Protonotaria citrea; above they are black with white wing-bars and yellow rumps. Scarcer Asian Paradise-Fycatchers Terpsiphone paradisi are hardly special plumage-wise, just black headed, rufous above, and light grey below, but boast long, flowing tails almost twice the length of their bodies.

Although Blue Robins and Rubythroats might give only brief, tantalising glimpses, Yellow-rumped Flycatchers Ficedula zanthopygia are show-offs. Below they glow yellow, like Prothonotary Warblers Protonotaria citrea; above they are black with white wing-bars and yellow rumps. Scarcer Asian Paradise-Fycatchers Terpsiphone paradisi are hardly special plumage-wise, just black headed, rufous above, and light grey below, but boast long, flowing tails almost twice the length of their bodies.

No such frills — nor even any colour — for male Siberian Thrushes Zoothera sibirica. They are slaty black, with a bold white supercilium (you barely notice the pale vent); a simple, striking pattern that surely places them among the ultimate `Sibes’.

No such frills — nor even any colour — for male Siberian Thrushes Zoothera sibirica. They are slaty black, with a bold white supercilium (you barely notice the pale vent); a simple, striking pattern that surely places them among the ultimate `Sibes’.

Flocks of Yellow-breasted Buntings Emberiza aureola add colour to the fields. Common Rosefinches Carpodacus erythrinus gather in trees, the red males breezily whistling to one another.

If all these birds sound like they won’t challenge your identification skills, try looking at some of the other songbirds occuring at this time. Phylloscopus warblers, for example. Now, even if the only `Phyllosc’ you know is Arctic Warbler P. borealis, you have a fair idea of what to expect — several members of this family look pretty much like Arctic Warblers, with greenish upperparts pale supercilium and dark eyestripe, and white or off-white underparts.

Identifying the early Pallas’s Leaf- P. proregulus and Yellow-browed [[Inornate]] P. inornatus inornatus, the later Eastern Crowned P. coronatus, Pale-legged P. tenellipes, Arctic, scarce Blyth’s Leaf- P. reguloides and — perhaps the latest of all — Two-barred Greenish P. plumbeitarsus warblers is based on characters like wing-bars (are there any?; if so, one or two, broad or thin?), rump (if yellow, Pallas’s — that was easy enough), presence of a crown stripe, tertial fringes, leg color, lower mandible color; and even the amount of mottling on the ear coverts — not easy to notice when a bird is busily moving through the foliage. Calls help too: I still find the very different calls are the best way of confidently distinguishing Arctic and Two-barred Greenish warblers, and the high, bluetail-like wheet helps with finding unobtrusive Pale-legged Leaf-Warblers. Call is also a big help in identifying Beidaihe’s brown Phylloscs: Dusky, Radde’s P. schwarzi, and — much rarer — Yellow-streaked P. armandii warblers.

Then there are the reed-warblers. The biggest — Oriental (Great) Reed-Warbler Acrocephalus (arundinaceus) orientalis — is straightforward enough, its face pattern helping to tell it from the similar Thick-billed Warbler Phragmaticola aedon. But picking out a Manchurian Paddyfield Warbler A. (agricola) tangorum (right) or a Blunt-winged Warbler A. concinens from the host of Black-browed Reed-Warblers A. bistrigiceps that arrive late in May relies on subtle features.

Then there are the reed-warblers. The biggest — Oriental (Great) Reed-Warbler Acrocephalus (arundinaceus) orientalis — is straightforward enough, its face pattern helping to tell it from the similar Thick-billed Warbler Phragmaticola aedon. But picking out a Manchurian Paddyfield Warbler A. (agricola) tangorum (right) or a Blunt-winged Warbler A. concinens from the host of Black-browed Reed-Warblers A. bistrigiceps that arrive late in May relies on subtle features.

Adding to the fun are Locustella — or `grasshopper’ — warblers, which I mostly see in flight: dark, thin-tailed Lanceolated Warblers (left), Pallas’s Grasshopper-Warblers L. certhiola with longer tails and reddish-brown rumps. Similar Japanese Marsh-Warblers Megalurus pryeri seem even more loathe to be seen well. Other brown skulkers, like Spotted Bush-Warblers Bradypterus thoracicus davidi and Gray’s Grasshopper-Warblers L. fasciolata, favour wooded areas.

Confused? I’d like to say you won’t be, after a visit to Beidaihe. But maybe you will: for some of the eastern Palaearctic warblers, identification techniques are still evolving.

Qilihai and Happy Island

South of Beidaihe are three estuarine areas: the muddy lagoon of Qilihai, which has only a narrow channel to the sea, the mouth of the Luanhe (Luan River), and a complex of sandbars and mudflats off the mouth of the Daqinghe. All are better than Beidaihe for coastal shorebirds — for although Beidaihe attracts an excellent variety of shorebirds (including freshwater specialists, 52 species to date), its mudflats and marshes are too small to hold large numbers. By contrast, the few visits we have made to these three areas suggest that at least the Daqinghe and Luanhe could rank as internationally important wetlands. Indeed, the Daqinghe complex may be one of the top shorebird sites in east Asia.

During a birding tour I co-led in May 1992, we made a two-day foray that covered the three sites. The trip to the Daqinghe, in particular, was something of a gamble, as the only other May visit I had made or knew of was the previous year when, at the end of the month, the mudflats were almost deserted. But the gamble paid off, with some spectacular birding — our list for the two days included 37 shorebird species.

During a birding tour I co-led in May 1992, we made a two-day foray that covered the three sites. The trip to the Daqinghe, in particular, was something of a gamble, as the only other May visit I had made or knew of was the previous year when, at the end of the month, the mudflats were almost deserted. But the gamble paid off, with some spectacular birding — our list for the two days included 37 shorebird species.

We began to the west of the Qilihai lagoon with at least 30 Little Curlews Numenius minutus. A close relative of the Eskimo Curlew N. borealis, Little Curlew is far commoner, but localised in its distribution.

Then, to the Luanhe. The shorebirds were in only modest numbers, but eight species of gulls included five Saunders’s in smart summer plumage, three unexpected Relicts, and a Little Gull Larus minutus — which may have been only the fifth for China. A plantation of young trees held a good concentration of warblers, thrushes and buntings — a sign of things to come. [Sadly, much of the Luanhe has reportedly been ruined by developments including fishponds; reportedly destroyed a Saunders’ Gull colony.]

The next day, we took a boat to a small island off the mouth of the Daqinghe. The mudflats we passed during the crossing teemed with shorebirds including Mongolian Plovers, Great Knots Calidris tenuirostris, Far-Eastern Curlews Numenius madagascariensis, and 14 endangered Asiatic Dowitchers Limnodromus semipalmatus; there were also Saunders’s Gulls and a flock of 5000 Common Black-headed Gulls Larus ridibundus. The island, with its sparse cover of shrubs, low trees, and long grass, teemed with songbirds — among the entries I made in the daily log were estimates of 230 (Siberian) Stonechats Saxicola torquata stejnegeri, 50 Brown Shrikes Lanius cristatus and 20 Dusky Warblers, along with 39 thrushes of six species, including an amazing seven White’s (Scaly) Thrushes Zoothera dauma in one bush.

Four days later, two Swedes were among a group of birders who were staying at Beidaihe and — when we returned with our tales of the rarities and teeming migrants — promptly visited the same island. Rather than just watch songbirds, they checked the mud off the island’s west coast, and found a shorebird roost with around 3500 Red Knot C. canutus and 1500 Great Knot, and at least 100 Asiatic Dowitchers. On a return trip later in the month, I too saw the roost; the knot flock was smaller, with fewer than 2000 birds, but still impressive, and other shorebirds that gathered as the tide rose included perhaps 1000 Bar-tailed Godwits Limosa lapponica. The day before, on a spit 10 km to the east, our group had found several hundred roosting shorebirds, and 3000 Eastern Common Terns Sterna hirundo longipennis.

Because the area is large, with many sandbars and small islands that could hold roosts, these figures may represent a fraction of the numbers of gulls, terns and shorebirds present during our visits. As to the numbers of birds that use the area during an entire spring — for the time being, at least, we can only guess.

Facing south across a shallow gulf — annual host to large flocks of birds of mudflats and scene of large songbird arrivals — the Daqinghe area is probably the closest you could find in Asia to the Upper Texas Coast; its prime birding area — the island with the teeming songbirds and high tide roost — a sort of Bolivar Flats and High Island combined. (And the name of the island? `Kwaile Dao’ — which, appropriately for birders flush with a successful visit, translates as `Happy Island’. [It now seems I helped invent this name! — after some misunderstanding with local guides, who indeed said the name was Kuaile Dao, though locals have since said it’s called Shijiutuo, which is far duller, with no ready translation.])

[Another wetland well worth a try is TIanmahu – Pegasus Lake, or Heavenly Horse Lake – to west of town, formed by reservoir at foot of mountains. Superb shallow margins, with grassland above.]

Beidaihe Migrants Suffering Declines

By the end of May, the spring migration is almost over; the birding is often sparse. But given fallout conditions — which in spring can include rain, or a threat of rain — there may still be good counts. On 7 June 1991, the town’s easternmost headland, Lighthouse Point, heaved with reed-warblers, Acrocephalus warblers and other songbirds.

Among the late-spring migrants are marsh birds — Yellow Bitterns Ixobrychus sinensis and Schrenck’s Bitterns I. eurhythmus, Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla, reed-warblers, and Locustella warblers, which time their journeys to coincide with the late growth of the emergent vegetation they lurk in.

Among the late-spring migrants are marsh birds — Yellow Bitterns Ixobrychus sinensis and Schrenck’s Bitterns I. eurhythmus, Baillon’s Crake Porzana pusilla, reed-warblers, and Locustella warblers, which time their journeys to coincide with the late growth of the emergent vegetation they lurk in.

At the end of May and in early June, there is the chance of what may be the last megatick of spring, the little known, now endangered Streaked Reed-Warbler Acrocephalus sorghophilus (right).

At the end of May and in early June, there is the chance of what may be the last megatick of spring, the little known, now endangered Streaked Reed-Warbler Acrocephalus sorghophilus (right).

Though, as with any migration watchpoint, the birding varies from one year to the next, it rarely disappoints. `When people hear what we’ve seen this spring,’ said one birder last year, `it will blow their minds.’

But mind-blowing or not, the migration at Beidaihe has a sobering side. Numbers of several species have fallen — dramatically in some cases — and the migration we see today may be only a shadow of the migration early this century.

I write `may be’ because, although information on birds in the Beidaihe area earlier this century is relatively plentiful, it is often hard to compare it with recent observations. It is not easy to judge whether numbers of a species have changed — and if they have changed, to what extent. Despite this problem, for many migrants, I know of no better information for assessing population changes. Beidaihe is probably the best studied migration watchpoint in east Asia, with studies dating back to 1910.

The first study was by British consul John D.D. La Touche, whose work on birds during his postings in China, and comprehensive — and still useful — A handbook of the birds of eastern China were significant contributions to the country’s ornithology. Through his own observations, and the specimens and sightings of collectors employed by the British Ornithologists’ Club’s Migration Committee, he worked on the birds at the nearby port of Qinhuangdao from 1910 to 1917.

Sadly, in reporting his results, La Touche rarely gave numbers, but instead used comments such as `abundant’, `common’, or `scarce’. It is hard to guess whether his uses of these terms would agree with ours; how would he have reported the migration at current levels? Because the terms `abundant’ and `very abundant’ appear through his papers far more often than we would use them today, was La Touche too liberal in using them?

A member of one of our survey teams argues that he was. I am not convinced; La Touche’s writings suggest he was level-headed. If so, several species have undergone a steep, sad decline in numbers. Indeed, La Touche wrote of `long streams’ of migrants passing down the coast in autumn: by today’s standards, his description seems exaggerated.

We are on safer ground in making comparisons with the work of Hemmingsen, who gave fuller accounts of the species he recorded, often with some numbers, sometimes with seasonal totals. Again, there are problems: Hemmingsen was a lone observer — albeit helped by servants whom he paid for finding flocks of passing cranes, geese and other birds — working under the constraints of Japanese occupation. The habitats have changed: Beidaihe today is radically different from the small town he would have known, a brash resort that has expanded as China’s economy has boomed.

Difficulties aside, comparing our results with those of La Touche and Hemmingsen paints a bleak picture. Though the data may be poorer, it seems the situation is much the same as in North America, with migrants in decline, and several causes for the dropping numbers, all rooted in a devastatingly huge human population.

As you would expect, habitat damage and destruction ranks high on the list of causes. That last megatick of spring, Streaked Reed-Warbler, occurred in fair numbers during La Touche’s time, but is rare today. Thought to breed in Manchurian wetlands — no one yet knows for sure — it winters in the Philippines, and it may be here that the problems lie, as several of the wetlands it favoured have been `reclaimed’.

The warbler is far from being alone as a wetland bird in decline. Hemmingsen saw up to 10,000 Bean Geese passing in autumn; even with teams of observers monitoring visible migration in shifts, our best count is only around 4000. Nor have the flights of Oriental White Storks and Common Cranes we have witnessed matched the peak numbers recorded by Hemmingsen. Flocks of Tundra (Bewick’s) Swans Cygnus columbianus bewickii are smaller and fewer — there have been none in recent autumns. Northern Pintail Anas acuta, which La Touche regarded as `perhaps the most abundant of the larger ducks’ is uncommon; Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri — `extremely abundant’ in autumn, according to La Touche — is now uncommon at best. Baillon’s Crake is apparently scarcer, so too Eurasian Coot Fulica atra, Little Curlew, Pallas’s Grasshopper-Warbler and Japanese Marsh-Warbler.

Baikal Teal Anas formosa perhaps deserves special mention; its population has not declined or plummetted, but crashed. It used to be abundant in east Asia — Hemmingsen once saw a flock of 1000-2000 at Beidaihe. Now it is uncommon throughout most of its range: at Beidaihe, there have been just 15 individuals recorded since we restarted studies in 1985. The reasons for the crash are unclear. Possibly, the chief cause is hunting.

Another anomaly among the dwindling wetland birds is Sanderling Calidris alba. Generally — because of increased coverage, or vanishing habitat elsewhere? — we have found shorebirds in higher numbers than Hemmingsen reported. Sanderling is different. Hemmingsen saw it `in flocks of, say, 30-100′; but our recent records are sparse, with single figures only. I wonder if it is a victim of disturbance on its wintering grounds, which for `our’ population are chiefly along the coasts of Southeast Asia. A beach specialist, Sanderling may have lost out to resorts built for sun-worshipping tourists.

Nearer to Beidaihe, the coastal wetlands have suffered. Hemmingsen reported Eurasian Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus osculans — which are of an endangered eastern race — at one of Beidaihe’s estuaries in June. Perhaps they bred; but no longer. Developments have left even the more resilient Little Terns Sterna albifrons pressed for space.

Fish ponds and shrimp ponds have spread like wildfire along the coast south of the town. The saltmarshes they have replaced will have been used by birds such as cranes, geese, and Great Bustards. All these birds still stop over — regularly, judging by our few visits — on an area of saltmarsh and rough fields that remains, sandwiched between shrimp ponds, at the Luanhe estuary.

This area also holds [now, 2005: held, as area reportedly ruined] perhaps a hundred breeding pairs of Saunders’s Gulls. Numbering only around 2000, and endemic to China as a breeding bird — its breeding grounds were first discovered only in 1987 — Saunders’s Gull must be among the country’s most threatened vertebrates. It is known to breed only at three sites in addition to the Luanhe: on the coast of southern Manchuria, in the Yellow River Delta, and north of Shanghai. At each of these, the shrimp ponds and other developments are moving in; already, the largest colony may have been destroyed by a reservoir, built to irrigate fields in a supposed wildlife sanctuary.

This area also holds [now, 2005: held, as area reportedly ruined] perhaps a hundred breeding pairs of Saunders’s Gulls. Numbering only around 2000, and endemic to China as a breeding bird — its breeding grounds were first discovered only in 1987 — Saunders’s Gull must be among the country’s most threatened vertebrates. It is known to breed only at three sites in addition to the Luanhe: on the coast of southern Manchuria, in the Yellow River Delta, and north of Shanghai. At each of these, the shrimp ponds and other developments are moving in; already, the largest colony may have been destroyed by a reservoir, built to irrigate fields in a supposed wildlife sanctuary.

There may be another disaster story unfolding: the the Three Gorges Dam, an overblown project that will flood a region that has, said a newspaper report, been compared to the Grand Canyon. The dam will disrupt the flow of the Yangzi, threatening species unique to the river such as the Yangzi River Dolphin and the Chinese Sturgeon. The mudflats at the river mouth will be affected. And the summer floods that fill huge lakes along the river valley may be reduced.

These lakes are of immense importance for waterfowl, especially in winter, when a corner of one lake — Poyang — may hold over a quarter of a million ducks, geese, swans, and cranes, including Siberians. China’s wintering Siberians, `lost’ to ornithology since late last century, were rediscovered at Poyang in the winter of 1980-1981; a reserve was established, and many more birds arrived to enjoy protection from rampant hunting. The Siberian Crane numbers at Poyang increased substantially, from 140 when they were first found, to a peak of 2900. Their boom may be short-lived.

Another cause of falling populations is deforestation. It is, however, hard to tell if its impact has been similar to wetland destruction, as gauging population changes of Beidaihe songbirds from past and recent records is more difficult than it is for waterfowl. But in one case — Siberian Blue Robin — the evidence seems irrefutable: there has been a serious decline. And there is a likely culprit: destruction of the tropical forests in its winter range.

`In the spring … this species swarmed Beidaihe about the middle of May and some time after,’ Hemmingsen wrote of the Blue Robin; sometimes, they were `too numerous to count’. And though Hemmingsen saw relatively few in autumn — because of the denser foliage — there is a report of a great fall of them at Beidaihe. One of the Beijing-based birding missionaries, G.D. Wilder, related rather casually that, `On September 10 [1923] the Siberian blue chat … was in the fields and on the grassy hillside among small pines in thousands….’ Only in one recent spring have numbers been high, with 250 one day — impressive, but not swarming; they have otherwise been easy to count. And autumn numbers have been modest; the fall Wilder described now seems like a remote fantasy.

Wintering in Southeast Asia, the Siberian Blue Robin is especially vulnerable to the deforestation as, at least in Thailand, it prefers lowland forests, which are invariably the first to be felled. Other migrants have surely suffered in much the same way. [Added early 2004: Problems surely worsening, with reports of increased logging in Indonesia (and elsewhere) to supply China’s demand for timber.]

The carnage looks set to spread to the north, to the breeding grounds of many migrants. With the break-up of the Soviet Union, and a more open Russia eager for revenue, Korean, Japanese, and other companies have been quick to offer their help in stripping the Siberian forests.

It may not be long before the effects of deforestation will show more clearly in the numbers of migrants occurring at Beidaihe. Within decades, the migration we know today could become as much an impossible dream as the migration in La Touche’s time is to us now.

Hunting worsens the blight of habitat loss and destruction. La Touche reported that at the end of last century egrets were devastated by plume-hunting. In the decades since his work, their populations may have recovered, but only slightly, suggesting hunting still takes a toll. [2005 update: egrets are becoming fairly common along the coast, with a substantial egretry now at Beidaihe.] Hunting has surely had a large impact on waterfowl — it may have devastated the population of Baikal teal, which has a habit of flying in dense flocks with predictable daily movement patterns. Perhaps it has also impacted Great Bustards, which similarly pass Beidaihe in smaller flocks than before, as well as many other birds.

An article in the February 1993 issue of China Environment News was headlined, `Hunters decimate Boyang’s wild birds.’ Each winter, according to the article, 300,000 ducks are killed by poisoned bait at Poyang (Boyang). (In turn, deaths of people poisoned by eating the ducks are common.) Waterfowl are also shot, even though this is `forbidden by the state’. They are sold in markets, with some — particularly rarer, supposedly protected species — destined for restaurants in southern China and Hong Kong. The market price per duck is around US$3. Geese cost almost US$10 each, while swans fetch roughly US$30 — more than many Chinese earn in a month.

Reflecting the hunting pressures they face, Beidaihe migrants are invariably wary. During the surveys at the town, we have seen gulls and thrushes shot for food, some other birds shot at purely for sport, and children with sling shots letting fly at warblers, bluetails, redstarts, and other songbirds that come within range. [2005 update: Now unusual to see this, thanks to education and law enforcement work.]

Trapping is widespread; despite laws against it, finches, buntings, and Northern Goshawks Accipiter gentilis are trapped at Beidaihe. [2005 update: there is still some trapping, but this is far less blatant, as the local government has made some efforts to catch and punish bird trappers.]

Often, it is hard to gauge the impact of trapping. But one example — from Thailand, but involving migrant songbirds that pass through Beidaihe — shows that it can be devastating. During surveys of a wildlife market in Bangkok during the late 1960s, Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava and Yellow-breasted Buntings were abundant, with totals of 16,721 and 87,209, respectively. Yet a repeat survey from December 1987 to December 1988 found none of either species. The likely reason is trapping at their communal roosts.

While both these species are still common at Beidaihe, they are by no means as abundant as La Touche described (Yellow Wagtail passed in `immense flocks’; Yellow-breasted Bunting swarmed in the crops). Trapping may be the reason here, too. Maybe many were — and still are — trapped in south China, where the Yellow-breasted Bunting, known as the `rice bird’, is popularly eaten. Maybe the wagtails and buntings trapped and sold in Thailand included birds that had traveled through Beidaihe.

Update, 2024: Yellow-breasted Bunting is now categorised as Critically Endangered, as numbers plummeted so severely.

Pesticides, which in many parts of east Asia are often applied liberally and carelessly, have probably reaped their own, grim harvest of wild birds. I know of no serious work on their effects on bird populations in China — whose Silent Spring is yet to be written. So, as too often when looking for causes for declines in Beidaihe migrants, we can do little better than guess when pesticides are to blame. Probably, they are chiefly responsible for steep declines in the numbers of Black Kites Milvus migrans and Rooks.

Beidaihe Breeding Birds and Old Peak

Amid the declines, and the doom and gloom, there are a few positive signs. Encouraged by the arrivals of increasing numbers of birders, the Beidaihe government has established a small reserve by the reservoir. Currently only fields with a little marsh, the reserve area will, if all goes to plan, be transformed into a lagoon overlooked by a visitor centre. [2005 update: still hoping this will work out; see article from May 2005 visit.] Another reserve has been designated at the western part of the Lotus Hills, affording some protection to rolling, wooded parkland. And, again partly as a result of our observations, the Luanhe mouth is now a reserve. [Hah! – supposedly. I heard this; later learned it had been largely ruined by new fishpond developments.]

Amid the declines, and the doom and gloom, there are a few positive signs. Encouraged by the arrivals of increasing numbers of birders, the Beidaihe government has established a small reserve by the reservoir. Currently only fields with a little marsh, the reserve area will, if all goes to plan, be transformed into a lagoon overlooked by a visitor centre. [2005 update: still hoping this will work out; see article from May 2005 visit.] Another reserve has been designated at the western part of the Lotus Hills, affording some protection to rolling, wooded parkland. And, again partly as a result of our observations, the Luanhe mouth is now a reserve. [Hah! – supposedly. I heard this; later learned it had been largely ruined by new fishpond developments.]

After massively abusing its environment during the 1960s and 1970s, China as a whole is taking some measures aimed at improving the situation. Among these is a `green wall’, a coastal shelterbelt of tree plantations. Though, as it does at Beidaihe, the green wall sometimes covers land that was used by resting storks, cranes, geese, and Great Bustards, it is surely an important habitat for migrant songbirds, which previously might have found little cover along long stretches of coast.

Tree planting has transformed Beidaihe. Writing in the 1920s, Wilder reported that with new plantations had come nesting Oriental Turtle-Doves Streptopelia orientalis, woodpeckers (Grey-headed Picus canus and Greater Spotted Picus major), Great Tits Parus major, and Black-naped Orioles Oriolus chinensis — all of which are common today. More recently, Chinese Pond-Herons Ardeola bacchus — which Hemmingsen did not record even as a visitor — have established a colony in a plantation beside the reservoir. [2005 update: there is now a substantial, thriving egretry, including Great and Little egrets and Black-crowned Night-Herons.] But even the best of the town’s woods has a man-made feel, and holds only a low diversity of breeding birds. For more natural woodland, we have had to look farther afield.

Tree planting has transformed Beidaihe. Writing in the 1920s, Wilder reported that with new plantations had come nesting Oriental Turtle-Doves Streptopelia orientalis, woodpeckers (Grey-headed Picus canus and Greater Spotted Picus major), Great Tits Parus major, and Black-naped Orioles Oriolus chinensis — all of which are common today. More recently, Chinese Pond-Herons Ardeola bacchus — which Hemmingsen did not record even as a visitor — have established a colony in a plantation beside the reservoir. [2005 update: there is now a substantial, thriving egretry, including Great and Little egrets and Black-crowned Night-Herons.] But even the best of the town’s woods has a man-made feel, and holds only a low diversity of breeding birds. For more natural woodland, we have had to look farther afield.

At the end of a bouncy, three-hour minibus journey from Beidaihe, we have found Old Peak, a scenic spot centering on a 1424m summit, highest of the mountains near the town. The ravine leading into the area is clothed with deciduous woodland — a welcome sight after the polluting factories and scrubby hillsides en route— and above it there is a conifer plantation in a basin flanked by craggy peaks, and more pockets

At the end of a bouncy, three-hour minibus journey from Beidaihe, we have found Old Peak, a scenic spot centering on a 1424m summit, highest of the mountains near the town. The ravine leading into the area is clothed with deciduous woodland — a welcome sight after the polluting factories and scrubby hillsides en route— and above it there is a conifer plantation in a basin flanked by craggy peaks, and more pockets

I have made four visits, all in late spring, when the songs of five species of cuckoos — Large Hawk- Cuculus sparverioides, Common C. canorus, Oriental C. saturatus, Lesser C. poliocephalus and Indian C. micropterus — ring out across the hills, Ring-necked Phasianus colchicus and Koklass Pucrasia macrolopha pheasants call from the dense cover, and Hair-crested Drongos Dicrurus hottentottus hawk insects among the trees.

Among other birds that probably or definitely breed locally are Chinese Nutchatch Sitta villosa, Eastern Crowned Warbler, Chinese Leaf-Warbler Phylloscopus sichuanensis (a recently discovered species, mainly known from central China), Elisae’s Flycatcher Ficedula elisae (formerly regarded as a species with this common name; then lumped with Narcissus Flycatcher F. narcissina for some reason; lately treated by discerning folk as separate species, though unfortunately with drab name Green-backed Flycatcher [why-oh-why-oh-why must great birds be given deadly dull names?]) – or Chinese Flycatcher – Siberian Blue Robin, Feae’s Thrush Turdus feae, Chinese Song Thrush Turdus mupinensis, Daurian Redstart, and Yellow-throated Bunting. Some of these are outside their published breeding ranges. Ornithologically, these hills have been little explored.

In the basin, there is a weather-carved outcrop of granite, with views down through a steep, wooded ravine to foothills with ruins of the Great Wall, and beyond to the coastal plain, gray and blurred in the haze. Standing here on a fine spring day, listening to the songs and calls from the regenerating forest, I can find hope for the future. Though declines may be inevitable, they need not be unchecked; it is worth fighting, trying to raise awareness and stimulate better law enforcement, and encourage reserve creation.

In the basin, there is a weather-carved outcrop of granite, with views down through a steep, wooded ravine to foothills with ruins of the Great Wall, and beyond to the coastal plain, gray and blurred in the haze. Standing here on a fine spring day, listening to the songs and calls from the regenerating forest, I can find hope for the future. Though declines may be inevitable, they need not be unchecked; it is worth fighting, trying to raise awareness and stimulate better law enforcement, and encourage reserve creation.

The autumn migration is like a mirror image of the spring, with the birds of late spring typically appearing earliest in autumn, the early spring birds not passing until the end of autumn. The image is far from exact: not all birds fit into this reverse order of appearance, and the abundances of different species often differ between the seasons (when they do, the numbers are invariably higher in autumn). Also, the autumn is more protracted. Whereas the passage in spring lasts perhaps four months at most, the autumn passage stretches over five months.

Early Autumn Migration at Beidaihe

Even as the last of the spring migrants are heading north, the first southbound birds of autumn may occur. On 17 June 1991 — the latest I have been at the town in `spring’ — I saw 17 White-winged Chlidonias leucoptera and six Whiskered C. hybrida terns flying south over the reservoir. Wilder and Hemmingsen also saw White-winged Terns flying south in June. In 1944, Hemmingsen’s June records were the prelude to great numbers in July: between 9am and 10:30am on 11 July, `flocks came continuously from Qinhuangdao bay … Many hundreds must have passed. The same was seen in the evening again and on many other days. Many thousands must have passed if the hours are allowed for in which no observations were made.’ These may have been failed breeders.

Even as the last of the spring migrants are heading north, the first southbound birds of autumn may occur. On 17 June 1991 — the latest I have been at the town in `spring’ — I saw 17 White-winged Chlidonias leucoptera and six Whiskered C. hybrida terns flying south over the reservoir. Wilder and Hemmingsen also saw White-winged Terns flying south in June. In 1944, Hemmingsen’s June records were the prelude to great numbers in July: between 9am and 10:30am on 11 July, `flocks came continuously from Qinhuangdao bay … Many hundreds must have passed. The same was seen in the evening again and on many other days. Many thousands must have passed if the hours are allowed for in which no observations were made.’ These may have been failed breeders.

Grey Starlings Sturnus cineraceus may also pass in numbers during July: `On the 4th of July, 1914,’ wrote La Touche, `thousands came from the north-east, flying south-west.’ Shorebirds start heading south — Hemmingsen recorded curlews from late June — and Common Black-headed Gulls return to the coast. But overall, July is relatively unproductive. And, with the flood of summer tourists, it is hardly the best time to visit Beidaihe.

In July 1987, two Danish birders spent four days at Beidaihe. One morning, they were up before dawn, and arrived at one of the prime shorebird localities, the Sandflats, to find it swarming not with birds, but with people, 1375 in all (the Danes did, however, see a Relict Gull fly by).

Late August is better; the earliest I have arrived is the 20th, which roughly marks the start of the Beidaihe autumn for birders. There are shorebirds in numbers — on one morning, 2000 shorebirds of 34 species were recorded at the Sandflats. White-winged Terns, which may be more regular at this time, are passing. Fork-tailed Swifts are abundant: on the afternoon of 30 August 1986 over 4000 streamed south. In the woods, there is a sprinkling of migrant songbirds. Arctic and Thick-billed warblers, Asian Paradise-, Yellow-rumped, Grey-streaked Muscicapa griseisticta, Dark-sided M. sibirica, and Asian Brown M. latirostris flycatchers seek insects among the dense summer foliage. Forest Wagtails Dendronanthus indicus, summer birds that swivel on disco hips, begin their withdrawal from the woods.

September Songbird and Raptor Flights

At the beginning of September, the sultry summer weather is almost over, and with it, thankfully, the flood of summer tourists. The variety and numbers of shorebirds are already declining, though still good; they may include one or two Nordmann’s Greenshanks. Relict Gulls — overwhelmingly young birds that strut busily about in search of crabs — can be expected from the middle of the month onwards.

At the beginning of September, the sultry summer weather is almost over, and with it, thankfully, the flood of summer tourists. The variety and numbers of shorebirds are already declining, though still good; they may include one or two Nordmann’s Greenshanks. Relict Gulls — overwhelmingly young birds that strut busily about in search of crabs — can be expected from the middle of the month onwards.

Visit the Sandflats early on almost any September morning and you will notice songbirds heading south. Often they arrive from over the sea, cut across the Sandflats, and head over the town — rather than fly around the triangle of land Beidaihe sits on, they take the short cut. There are flocks of Yellow Wagtails, parties of Richard’s Pipits Anthus richardi, Olive-Tree Pipits Anthus hodgsoni, and buntings, and clusters of bounding Chestnut-flanked White-eyes Zosterops erythropleura. While calls help you identity and find the birds, many pass unseen. White-eyes seem to be masters of invisibility — the stealth migrants of Beidaihe. All too often, I have heard calls a-plenty, but looked up to see only blue sky.

Songbird flights like this are far less evident in spring, when the only consistent reports are from Eagle Rock, a rocky headland that overlooks the Sandflats. No matter where you are at Beidaihe in autumn, you may see and hear passing songbirds. In addition to passing over the Sandflats, songbirds travel along the south coast of town and head over the Lotus Hills — from where you can see distant flocks moving south over the plain. Even as you cycle the streets through town, or walk through the grounds of your hotel, you might notice songbirds passing over. There may also be terns, gulls, shorebirds, and raptors.

Songbird flights like this are far less evident in spring, when the only consistent reports are from Eagle Rock, a rocky headland that overlooks the Sandflats. No matter where you are at Beidaihe in autumn, you may see and hear passing songbirds. In addition to passing over the Sandflats, songbirds travel along the south coast of town and head over the Lotus Hills — from where you can see distant flocks moving south over the plain. Even as you cycle the streets through town, or walk through the grounds of your hotel, you might notice songbirds passing over. There may also be terns, gulls, shorebirds, and raptors.

White-winged and Whiskered terns often take the short cut over the Sandflats and across the town. So do many shorebirds — some of which might arrive from the north, touch down on the Sandflats, then continue their journeys. Outstanding among the flights of September shorebirds are Grey-headed Lapwings Vanellus cinereus. Rather drab on the ground, yet bold black and white in flight, they might travel in flocks of 200 or more, with a good morning’s passage totalling perhaps two or three thousand. On such mornings, up to several hundred Pied Avocets Recurvirostra avosetta might also fly south. And, almost certainly, there will be Pied Harriers, which fly low in the early hours, their numbers often dwindling by mid-morning, but occasionally building as they take advantage of thermals to fly high above the plain.

Beidaihe’s best place for watching the Pied Harriers, and many of the other birds that overfly the area, is the Lotus Hills. From 20 August to 20 November 1986, our survey team spent 854 hours monitoring visible migration from the hills. Including unidentified pipits, buntings, and the like, we recorded a grand total of 262,970 birds of 160 species — an average passage rate of a little over 300 birds an hour (there were, though, some long, long, near-birdless hours).

Beidaihe’s best place for watching the Pied Harriers, and many of the other birds that overfly the area, is the Lotus Hills. From 20 August to 20 November 1986, our survey team spent 854 hours monitoring visible migration from the hills. Including unidentified pipits, buntings, and the like, we recorded a grand total of 262,970 birds of 160 species — an average passage rate of a little over 300 birds an hour (there were, though, some long, long, near-birdless hours).

In September, the Lotus Hills are especially good for watching raptors including Pied Harriers, as well as Oriental Pratincoles, and White-throated Needletails Hirundapus caudacuta. The needletails can seem drawn to the hills as if by a magnet; on good days, flocks arrive from the north, glide and circle around, then, with a few flaps of their wings, whoosh overhead like speeding bullets, and vanish to the south.

As in the spring, the intensity of visible migration fluctuates. Days at the Lotus Hills can be slack, with the skies seeming deserted by all but the resident swallows and, very likely, Northern Hobbies Falco subbuteo swooping after dragonflies. More usually, there is some passage to be seen. And, occasionally, there are wave days.

Days like 12 September 1986. We arrived at the watchpoint as dawn was breaking. Already, there were songbirds heading over. There were also Pied Harriers, gliding low over the ridges and across the fields below. With the sky clear, and the west wind light, the day warmed, and the harriers climbed higher. Their numbers increased, and soon they were streaming overhead in squadrons, or soaring in kettles above the hills and plain. Eastern Marsh-Harriers (Striped Harriers) Circus spilonotus, Black Kites, Crested Honey-Buzzards Pernis ptilorhyncus, and Japanese Sparrowhawks Accipiter gularis were among the other raptors that joined the kettles, then, high above us, glided southwards. [Several raptors we’ve seen passing Beidaihe had chunks of flight feathers missing, like the Crested Honey-Buzzard in the photo – as they had been shot at?] Oriental Pratincole calls, harsh and urgent, resounded; alerted to them, we scanned the sky in search of their flocks, which might be swirling in the rising air and sometimes went unseen — like white-eyes, they could be hard to find.

Days like 12 September 1986. We arrived at the watchpoint as dawn was breaking. Already, there were songbirds heading over. There were also Pied Harriers, gliding low over the ridges and across the fields below. With the sky clear, and the west wind light, the day warmed, and the harriers climbed higher. Their numbers increased, and soon they were streaming overhead in squadrons, or soaring in kettles above the hills and plain. Eastern Marsh-Harriers (Striped Harriers) Circus spilonotus, Black Kites, Crested Honey-Buzzards Pernis ptilorhyncus, and Japanese Sparrowhawks Accipiter gularis were among the other raptors that joined the kettles, then, high above us, glided southwards. [Several raptors we’ve seen passing Beidaihe had chunks of flight feathers missing, like the Crested Honey-Buzzard in the photo – as they had been shot at?] Oriental Pratincole calls, harsh and urgent, resounded; alerted to them, we scanned the sky in search of their flocks, which might be swirling in the rising air and sometimes went unseen — like white-eyes, they could be hard to find.

With the passage slower from mid-afternoon, but continuing until dusk, the day’s watch lasted over 12 hours. Tallies of birds that passed south included one Osprey Pandion haliaeetus; 15 Black Kites; 170 Crested Honey-Buzzards; 4 Eastern Marsh-Harriers; 10 Eurasian Kestrels Falco tinnunculus; 9 Northern Hobbies; 34 Amur Falcons Falco amurensis; 152 Japanese and 27 Northern Accipiter nisus sparrowhawks; 791 Oriental Pratincoles; 1015 Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica; 45 Yellow, 121 White Moticilla alba and two Grey M. cinerea wagtails; 174 Richard’s, 31 Olive-Tree and 15 Red-throated Anthus cervinus pipits; 9 Ashy Minivets Pericrocotus divaricatus; 14 Black-naped Orioles; 18 Black Drongos Dicrurus macrocercus; 11 Common Rosefinches; and, most outstanding, 2957 Pied Harriers.

Helped by this day, our autumn 1986 survey produced a staggering total of 14,534 Pied Harriers. Quite possibly, this figure represents a high proportion of the world population of this species.

Cold Fronts Driving Beidaihe Autumn Migration

By the beginning of October, autumn is well underway; leaves are turning from green to brown, and only the hardiest bathers swim at beaches that thronged with tourists just a few weeks earlier. The variety of migrants perhaps peaks around this time, though not so sharply as it does in spring, and with a different mix of birds.

The first of the season’s cold fronts may arrive early in the month, sweeping down from Siberia on its way to south China.

Ahead of these fronts, there may be falls of songbirds. They arrive on fine, still days when the air is hazy, and becoming hazier, and visible migration may have ground to a standstill — and festoon the woods and coastal gullies.

I remember walking down Lighthouse Point on one of these fall days, following the path to the tip of the headland that might take only ten minutes at a brisk pace. It was alive with birds, especially Pallas’s Leaf-Warblers, which seemed to be in every tree, often in small, active parties. By my estimate, there were at least 60 of them; other birds included 13 Red-flanked Bluetails, seven Dusky, four Radde’s, and six Black-browed Reed-Warblers, and a Bluethroat Erithacus svecicus.

I remember walking down Lighthouse Point on one of these fall days, following the path to the tip of the headland that might take only ten minutes at a brisk pace. It was alive with birds, especially Pallas’s Leaf-Warblers, which seemed to be in every tree, often in small, active parties. By my estimate, there were at least 60 of them; other birds included 13 Red-flanked Bluetails, seven Dusky, four Radde’s, and six Black-browed Reed-Warblers, and a Bluethroat Erithacus svecicus.

Pooling everyone’s records for the day’s birding at Beidaihe, there were 395 Pallas’s Leaf-Warblers; among the other songbirds in the influx were 68 Red-flanked Bluetails, 28 Yellow-browed, 45 Dusky and 18 Radde’s warblers, 5 Pallas’s Grasshopper-Warblers, 35 Black-browed Reed-Warblers, 42 Pallas’s Reed-Buntings Emberiza pallasi, 43 Little E. pusilla, and 5 Yellow-browed E. chrysophrys buntings.

Later that same month, during another influx as another cold front approached, I watched thirty Red-flanked Bluetails feeding in and around just six trees. In all, we recorded 210 bluetails at the town that day; there were also 21 Dusky Warblers, 285 Pallas’s Reed-Buntings, and 216 Rustic and 86 Yellow-throated buntings.

Later that same month, during another influx as another cold front approached, I watched thirty Red-flanked Bluetails feeding in and around just six trees. In all, we recorded 210 bluetails at the town that day; there were also 21 Dusky Warblers, 285 Pallas’s Reed-Buntings, and 216 Rustic and 86 Yellow-throated buntings.

I am not sure why the birds should arrive in this fine weather. Maybe the insectivores, especially, gather to take advantage of the mild conditions, and fatten up before continuing the migration. Maybe they gather at the coast in readiness for the weather to come.

The fronts bring migration weather. Often, they are followed by classic autumn migration conditions, with brisk northerly or north-westerly winds and clear skies. And once the fronts have moved through, the teeming songbirds are gone.

Clouds roll in as a front arrives. The air is usually still. Then, the wind starts to blow, and the temperature drops. It may rain, or even snow if it is late in the autumn. I remember mornings spent in hotel rooms, waiting for the weather to improve so we could go out and watch for visible migration; and one day when it rained from morning to late afternoon, and we stood on a sheltered hotel balcony, watching thousands of Bean Geese and Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus as they rushed south, down the wind.

Once the rain has stopped, it is time to head for a watchpoint, and quickly. The front that swept through after the Pallas’s Leaf-Warbler fall brought rain. The front arrived during the night, and the rain was still falling after daybreak. Once the rain had died away, we left the hotel.

Even as we stepped out of the lobby, we looked up to see a flock of 70 Grey Herons Ardea cinerea passing over. More flocks swept down the east coast, often arriving from low over the sea to the northeast, and scattering like leaves tossed on a breeze as they met the low cliffs, and the air currents swirling in the buffeting wind. For two hours they passed almost non-stop: we recorded 1417 Grey Herons, also 135 Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo, and two White Spoonbills Platalea leucorodia. Then, there was a lull. The sky cleared around midday, and the migration surged again — most of the day’s 21 Black Storks Ciconia nigra, 26 Northern Sparrowhawks, 21 Northern Goshawks, 427 Common Buzzards Buteo buteo, 1167 Daurian Jackdaws, and 2693 Rooks or Carrion Crows Corvus corone were seen from the Lotus Hills during the chilly afternoon.

Even though, with the passage of a cold front, a `wave’ of passing migrants seems almost guaranteed, we have not yet been able to predict just what the principal species will be. Except, perhaps, on one wave day during autumn 1986.

On 21 October, Tao Yu, a young Chinese ornithologist who joined us for much of the autumn, arrived at the Lotus Hills watchpoint and said, `Yesterday, I had a dream — many crows.’ We had already logged passing flocks of Carrion Crows, Rooks, and Daurian Jackdaws. More followed; they streamed south in the afternoon, and the day became the best crow day in recent years, with totals of 3175 Daurian Jackdaws and 9243 Rooks or Carrion Crows. We waited for Tao to have another dream — preferably of great rarities such as Crested Ibis Nipponia nippon or Crested Shelduck Tadorna cristata. But to no avail.

The waves do not always immediately follow the fronts. Once, three of us spent hours scanning the skies, and sheltering as best we could, as a cruel west wind blew in from across the plain. We saw hardly anything: three Northern Goshawks and thirty-one songbirds in eight hours. The next day, with a northeasterly, was better — there were 777 Northern Lapwings and 713 Rooks or Carrion Crows. But it was on the third day that we saw the sort of wave we had been hoping for. It wasn’t a huge wave, but it was memorable.

The winds were light on 2 November 1990, mostly northeasterly in the morning, southerly in the afternoon. The morning was slack. From lunchtime, cranes began passing. There were Red-crowneds, Commons, and Hoodeds, all in modest numbers. And there were Siberians, which were swirling, distant white birds as we found them, soaring on thermals north of the town. With height gained, they arranged themselves into chevrons and flew, unhurried but purposeful, into the light breeze. Many passed close to the hills, which again rang to their strident calls; the sights and sounds were magical. In all, the day produced 389 Siberians — more than the seasonal total in each of the past four years, and the most in a day at Beidaihe since Hemmingsen recorded 545-645 on 28 March 1945.

Oriental Storks, and the Grand Finale of the Beidaihe Birding Year

With each cold front, winter is a step closer. The fresh winds tug leaves from trees, the air chills, and the mix of birds changes — some of the species present before a front arrived may not be seen again during the year; with the passage of the front, there may be other species making their first appearance of the autumn.

By early November, winter visitors are returning, and the birding is somewhat as it was in March. But, for the most part, it is more varied and interesting than in March. Notable among the birds that are commoner at this time is Oriental White Stork.

Until I first read Hemmingsen’s report on Beidaihe, I was unaware that there was a white stork in the Far East. From the description he gave, it differed from the bird I knew from visits to Israel — the European White Stork Ciconia ciconia. For instance, its bill was longer, and blackish, not red. Hemmingsen had seen only a few in spring, but they could be abundant in late autumn: a flock of 1000-1500 once stayed near the town for two days, probably held up by a fog; during another autumn, he estimated that he saw 1000-4000 birds one day.

By autumn 1986, when the Oriental White Stork was increasingly recognised as a distinct species from its European cousin — besides its long black bill, it is larger, and behaves differently — surveys on its winter grounds and breeding areas suggested the world population was, at most, just 1200. Because of hunting and poisoning by agricultural chemicals, it had been extirpated as a breeding bird in Japan, where it was common last century. Korea, where it was `locally common’ in the 1940s, had lost its breeding birds by the late 1980s. Only southeast Siberia and neighbouring parts of China near the Amur River Valley still held breeding birds, which mostly wintered along the Yangzi valley, sharing the haunts of the Siberian Cranes.

We had recorded only 12 in spring 1985 — but, because of Hemmingsen’s records, I was hopeful we might see good numbers passing in the 1986 autumn. My hopes were more than realised.

The storks began appearing in October, huge birds that rivaled the cranes for majesty but glided past in silence and were not in chevrons, but in random flocks. At dusk on 29 October, a large flock glided out of the gloom, and passed low over the plain to our west: we estimated there were 280 birds, about a quarter of the known world population. In November, we saw more giant flocks, and we soon overhauled the 1200 mark, eventually finishing with 2729 Oriental White Storks — perhaps most of the birds that were alive at that time.

The storks began appearing in October, huge birds that rivaled the cranes for majesty but glided past in silence and were not in chevrons, but in random flocks. At dusk on 29 October, a large flock glided out of the gloom, and passed low over the plain to our west: we estimated there were 280 birds, about a quarter of the known world population. In November, we saw more giant flocks, and we soon overhauled the 1200 mark, eventually finishing with 2729 Oriental White Storks — perhaps most of the birds that were alive at that time.

But while our count had more than doubled the estimated world population — to around 3000 — we hadn’t seen any flocks approaching 1500 birds, nor any days with over 1000 birds, as had Hemmingsen. And we have since failed to log more than 2000 Oriental White Storks in an autumn. Despite protection measures — on paper at least — for the species, hunting, habitat destruction, disturbance and poisoning continue; they may have caused the population to fall since 1986, and numbers will probably fall further as more wetlands are `reclaimed’.

In November, the overall migration goes into a decline. There may be interesting birds around the town — perhaps flocks of Bohemian Bombycilla garrulus or Japanese B. japonica waxwings, and one or two handsome Güldenstädt’s Redstarts Phoenicurus erythrogaster. Visits to the Luanhe and Daqinghe can be productive, with a good chance of seeing cranes, geese, and Great Bustards on the ground, as well as Chinese Grey Shrikes Lanius excubitor, late Saunders’s Gulls, and, maybe, Relict Gulls.

In November, the overall migration goes into a decline. There may be interesting birds around the town — perhaps flocks of Bohemian Bombycilla garrulus or Japanese B. japonica waxwings, and one or two handsome Güldenstädt’s Redstarts Phoenicurus erythrogaster. Visits to the Luanhe and Daqinghe can be productive, with a good chance of seeing cranes, geese, and Great Bustards on the ground, as well as Chinese Grey Shrikes Lanius excubitor, late Saunders’s Gulls, and, maybe, Relict Gulls.

Strictly, the autumn migration will continue until late November; regular passage will then halt, and new arrivals are only likely if hard-weather movements push birds down from the frozen north.

But the passage does not just fizzle out. In November, the stage is set for the grand finale of the Beidaihe bird year: the peak of the autumn crane migration. Only after experiencing this do I feel content to leave the town in late autumn.

The largest crane wave recorded since Hemmingsen’s time was on 10 November 1990: there were five crane species in all, with totals of 2728 Commons, 328 Hoodeds, 135 Red-crowneds, 6 White-napeds, and 111 Siberians, and 396 unidentified. It was another wave which did not immediately follow a cold front.

With a front already through, three of us arrived early at the Lotus Hills watchpoint on 9 November, hoping for a good day. The wind was brisk, north-north-easterly, becoming north-westerly by mid-morning, and westerly by mid-afternoon. The sky was clear, the air cold — where it was shaded from the sun, ice in a granite hollow remained frozen all day. Raptors were the day’s stars: there were 13 species, including 190 Upland Buteo hemilasius and four Rough-legged B. lagopus buzzards, six Eurasian Black Vultures Aegypius monachus, three White-tailed Eagles, and one each of Greater Spotted Aquila clanga, Steppe A. nipalensis and Imperial A. heliaca eagles. There were also 135 Oriental White and four Black Storks, 14 Great Bustards, ten Red-crowned Cranes, and 491 Common Cranes, most of which passed in the late afternoon — the forerunners of the wave.

The next day, the sky was again clear, and the early wind was moderate, north-northeast. But the wind soon became light, swinging to southerly in the late morning — not so promising. By midday, numbers of migrants logged were low.

But, soon after 28 Commons flew north, a flock of 85 Common Cranes flying south marked the start of the passage.

We recorded a succession of small, medium and, occasionally, huge flocks. Just one hour, from 3pm to 4pm, produced 1504 cranes of four species. Most were traveling to the east of us, perhaps well out over the sea, and cutting southwest; this seems typical of the big autumn flocks. A few smaller flocks passed close to our watchpoint.

After 4pm, the passage ebbed, with only 26 cranes in 30 minutes. But then, in the gathering gloom, the wave gathered pace again, with more flocks over the sea. They became harder to see, and near impossible to identify; just lines of black dots against the murky grey of sea and sky. At 5:15pm, with night falling, we left the watchpoint.

It took us maybe 20 minutes to walk down from the hills. As we walked, the darkening sky resounded to those haunting, timeless sounds; the choruses of cranes, calling themselves on southwards.

If you’re interested in visiting Beidaihe, you could contact Jean Wang of the town’s Sky and Ocean Travel Service, which has often handled birding groups/individuals – can arrange excursions to Happy Island etc. Email: bits [at] 0335.net or bsots [at] 263.net